Review: Tina the Musical (Aldwych Theatre)

The musical based on the life of the rock’n’roll legend has its world premiere in the West End

© Manuel Harlan

As the co-creator of Mamma Mia! director Phyllida Lloyd was responsible for one of the great joy-giving jukebox musicals of our times. The combination of ABBA's bright, breezy pop and a plot of romantic misunderstandings, produced a perfect synthesis of bubble gum pleasure.

In returning to the jukebox form with Tina, Lloyd steps into far darker territory. Here the songs of the great Tina Turner are used, with intelligent conviction, to chart the trajectory of her life. But the story of one of pop's great survivors must of necessity handle the terrible things she has had to overcome – and that doesn't always make for comfortable viewing.

You can see the show's tactics from the opening scene. The orchestra starts to pulse the beat of "The Best", and that unmistakable late-Tina 1980s silhouette appears, spotlighted in a doorway, spiky maned and mini-skirted. But instead of providing the expected release into a belting ballad, the action smoothly circles backwards into an ancestral chant and then to Tina's childhood, with a rendition of "Nutbush City Limits" sung, as a hymn, at a revival meeting by her preacher father.

It's sophisticated and clever, thwarting expectations even as it encourages them. From then on we follow Tina's evolution from sparky but ill-treated Anna-Mae Bulloch to legendary rock idol. Katori Hall (who wrote The Mountaintop about Martin Luther King) has provided a book (with Frank Ketelaar and Kees Prins) that skips swiftly along, full of emphasis on "the dream" and "that voice that comes tumbling out of you".

She doesn't entirely avoid biopic cliché – "imagine you're singing to the God in your yourself", implores Phil Spector at one point – but she smuggles in some interesting observations about sexism, racism and ageism. And Mark Thompson's designs, which use oblongs of fluorescent light to delineate each scene, flow with simple efficiency, vividly filled by Jeff Sugg's projections, full of pulsing light and passing landscapes.

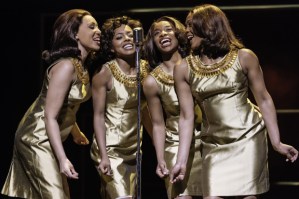

The routines – choreographed by Anthony Van Laast who has a lot of fun reincarnating period styles – are dazzling. Lloyd's direction seems effortlessly fluid and emphasises Tina's feminist principles, her relentless will to succeed, and to provide for her family, her toughness, her talent and her desire "not to be any man's puppet".

The problem for me is that, at least for the first act which charts her relationship with Ike, what we actually witness is a strong woman being brought down by multiple acts of violence. The more shocking the violence is – and both Ike's abusive behaviour and that of Tina's father elicit gasps from the audience – the more difficult it is to accept within the framework of a glossy musical.

And beyond saying that he has "a way of forcing folks into doing what they don't want to do", the show can't explain why Tina puts up with such extraordinary treatment for 16 years – from the moment he first hurls a cymbal at her when she dares to suggest a new groove, to the extensive and wounding beatings that finally drive her to seek her freedom. Perhaps it is inexplicable.

© Manuel Harlan

But what it does do, is use Turner's own back catalogue in inventive and imaginative ways to chart her difficult journey. The scene where Ike looks up at the Mississippi stars and Tina sings "Better Be Good to Me" at his still figure, more as a warning than a love song, is fiercely effective; so is the moment in the second half when, struggling to get her career back on track, she sings "Private Dancer" as a bitter, sardonic song of mourning. There are also brilliant, more direct routines to songs such as "Proud Mary" and a terrific scene in the studio where Spector encourages Turner to find her inner goddess and let rip with "River Deep, Mountain High".

In every incarnation, beaten and proud, the American actress Adrienne Warren is magnificent as Tina. She has a knack for finding a wide-eyed joy when things are going well, and a deadness behind the eyes when they are not. Without actually sounding exactly like Turner, she catches the thrill of that throaty, powerful voice, its rolling way with a lyric – and she perfectly mimics those little skittering kicks and runs that made her a formidable stage presence late into her 60s.

Given the thankless task of playing Ike, Kobna Holdbrook-Smith doesn't stint on his nasty, swaggering jealousy and arrogance. But he does manage to suggest the fear of not being appreciated that lurks behind that strutting, smooth exterior. Other characters are little more than cameos, but Aisha Jawando as Tina's sister, Madeline Appiah as her bitter mother and Ryan O'Donnell as her manager all make their mark.

In the end, the audience gets what it has wanted from the start – a singalong to the perfectly reproduced hits. Rather like the woman herself, the steamroller that is Tina flattens you into submission.