Review: The War of the Worlds (New Diorama Theatre)

© Richard Davenport

Theatre company Rhum and Clay are big on their adaptations. With this newest staging of The War of the Worlds following on from the successful reinterpretation of Dario Fo's Mistero Buffo monologue in 2018, the company has gone from a biblical story to a story of biblical proportions. But how exactly does a book featuring giant metallic laser-killing aliens work in a north London fringe venue?

The truth is, this The War of the Worlds is less about the content of HG Wells' story or even Jeff Wayne's musical (sorry anyone expecting a Liam Neeson hologram), but instead about actor Orson Welles' radio broadcast, performed live on Halloween in 1938. The broadcast was so shocking and mimicked the format of a news bulletin so closely that many listeners believed the performed alien invasion to be the truth (roughly 1.2 million people, according to later research). For Rhum and Clay, Welles basically created the original fake news.

Devised by the company with further writing by playwright Isley Lynn, this 85-minute reimagining freewheels between the '30s and the present day – at first we're watching Welles conduct his radio broadcast of Wells' novel from a recording studio, wooden pipe in hand. Suddenly it's in the present day, following drippingly earnest first-time podcaster, Meena (Mona Goodwin), as she travels from the UK to New Jersey (where Welles set his performance). Why is she there? Something to do with a quest to discover the veracity of an old letter belonging to a neighbour – like a slightly slipshod blend of S-Town and a Welles biopic.

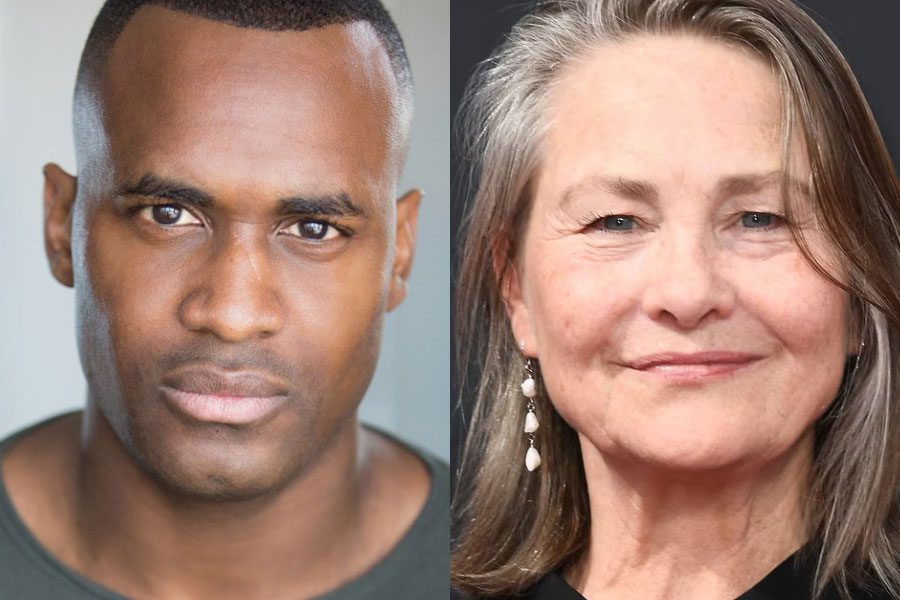

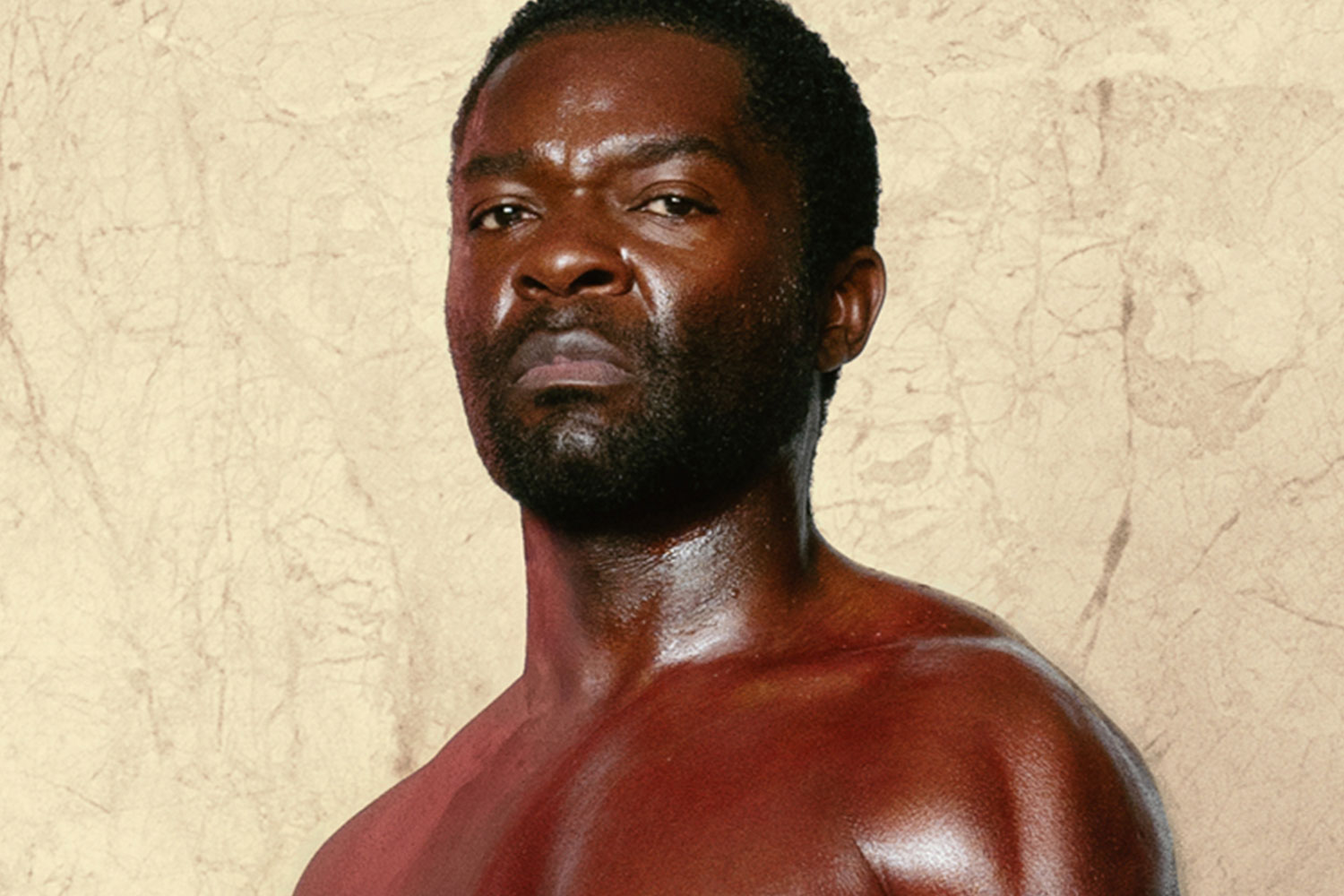

The cast of four makes for a whirling multi-roling ensemble, especially Julian Spooner who captures Welles' twangs to a t. Bethany Wells' (another Wells!) costume design, putting the alternative into alternative facts, uses button-up collars and a neutral pallet to unnervingly contradict the stark, saturated primary colours in Nick Flintoff and Pete Maxey's lighting, which has a few nods to sci-fi strains of Wells' original work. It's Benjamin Grant's sound design that stands out (fortunate, for a show largely set in a recording studio set), with analogue radio sounds clashing with crisper podcast tones.

Some beats start to feel a tad superfluous, and it's really the '30s scenes that lift the show through well-drilled execution – aided by some great movement direction from Matthew Wells (so many Wells / Welles, I'm almost welling up).

But the overall premise is just juicy – how far does a medium of communication affect our ability to believe a fabrication? If something is tweeted, or published on a seemingly real news site, or played out over the radio, or listened to on a podcast, why are we naturally inclined to trust its accuracy? The show may be more of a war of words than a war of the worlds but it's all the better for it – Liam Neeson can keep his hologram.