Review: The American Clock (Old Vic)

© Manuel Harlan

There's a mini Arthur Miller season underway across London at the moment. His The Price, a semi-autobiographical piece about a family whose dreams are dashed by the Great Depression has opened this week. All My Sons and Death of A Salesman about families whose dreams are destroyed by a false notion of the American dream fostered by the Great Depression are due to open soon.

In the meantime, here's The American Clock, from 1980, which is actually the history of the Great Depression, pegged around the semi-autobiographical story of a family who lose millions and the aspirations of their Communist-sympathising, young writer son.

If nothing else, the collision of these pieces emphasises just how deeply the instability of voracious capitalism – the kind that prizes stocks over goods, that values big business over small ventures – was seared into the playwright's mind, thanks to his own family's ruin in the 1929 Wall Street crash. In our own times, he looks uncannily prescient in his warnings about the way people can be cut adrift by the system. If they had the money to go to the theatre, the people now visiting food banks, and living in communities that have been stripped of all pride and all resources would recognise themselves in the distressed souls queuing for relief in this epic play.

But being right doesn't guarantee good theatre. And The American Clock is a very odd construct indeed. Subtitled a vaudeville, it combines a thin plot about the Baum family, with great chunks of experience gleaned from the journalist Studs Terkel's Hard Times, a book of testimony about the depression and its aftermath, and then weaves in some songs of the period for good measure.

Rachel Chavkin's production does her absolute dazzling best with it. She sets the entire thing in the round, putting half the audience on the Old Vic's stage, staring out into its glistening auditorium. She has tripled the Baum family, so that it moves from being white Jewish, to South Asian, to African-American in order to emphasise the multi-cultural nature of American society. She peppers the play's vignettes with a wonderful score by Justin Ellington and sound designer Darron L West and energetic use of the revolve and fantastic, sharp dance routines from Ann Yee.

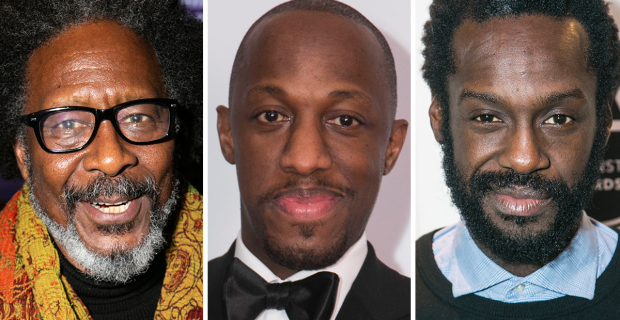

She has a brilliant, committed, hard-working cast, led by Clarke Peters, a man whose grave charisma could make the reading of a telephone book compelling. He plays Robertson, one of the few investors to predict the crash and cash up and our guide to all subsequent events. Peters' grace and relaxed delivery hold things gently together; he is also superb as a hungry, ruined father and as one version of Moe Baum. When his narration vanishes in the second half, you miss him desperately.

All this effort yields some compelling scenes and many memorable images: the water dripping down Chloe Lamford's set, wiping the chalked stock prices away as the market plunges and men begin to jump out of windows, faced with ruin; the use of a dance marathon to catch the cruelty of an exhausted society staggering on; the tap dancing head of General Electric (Ewan Wardrop) who resigns because innovation is being squashed by business and "this is a corporate country now". There are scenes which reveal just how close America came to revolution, as farmers revolt against bank foreclosures, and a telling moment when a black cook notes that the crisis only became serious because it affected white people.

The performers pull great moments of emotion from the script, too. Golda Rosheuvel shines both as a committed Communist organiser and as the third version of Rose Baum, cracking under the strain; Clare Burt has a quiet dignity and the sweetest of smiles as the first version of Rose. Francesca Mills makes the character of Daisy, a girl who becomes suddenly popular because her mother owns an apartment building, into a warm and witty person. Fred Haig, Jyuddah Jaymes and Taheen Modak all find different notes in their portrayal of Lee, the idealistic writer.

But their very excellence consistently reveals the thinness of the material they are working with. The history lesson just goes on and on for three hours, with a plot occasionally emerging. There was a point when I thought it might never end, but then, as with the Depression, the War looms and it is over. For all Chavkin's efforts, it is a long night.