Review: The Price (Wyndham's Theatre)

©Nobby Clark

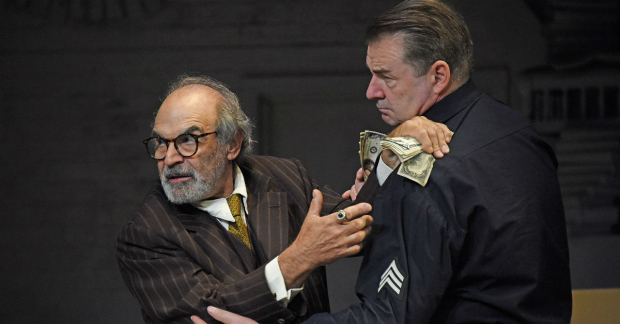

Arthur Miller isn't a writer you associate with comedy but from the moment David Suchet comes onto the stage as the used furniture dealer Gregory Solomon in this revival of his 1968 play, The Price, the laughs start to flow. Indeed, on opening night they came so fast that Brendan Coyle, as Victor Franz, the man who is trying to sell the furniture could hardly disguise his own fits of the giggles.

No wonder, when you've got lines such as the old man's claim that he was one of five Solomon brothers who made their way as acrobats. "I was the one at the bottom," he says, deadpan. "Nothing ever stopped me. Only life." Suchet delivers the lines with a vaudeville's timing. The performance has a deftness, a lightness of touch. He smooths out his battered business card as if it were made of gold, eats an egg with delicate fingers, cocks his head, sniffing the air, slightly fearful when Victor's brother Walter (Adrian Lukis) arrives and the negotiations turn tougher.

But he also utterly understands the seriousness of Miller's purpose. The Price, like so much of the playwright's work centres on a family torn apart by compromise and illusion, in this case by the terrible pressures placed upon the two Franz sons by the 1929 crash which turns their father from a millionaire to a pauper overnight. Victor gives up his hopes of being a scientist to join the police and care for their dad; Walter turns his back on the family home, in the ruthless pursuit of his own career and the money that will make him secure for ever.

Because this is Miller, drawing on the deep trauma of his own family history, nothing is quite as simple as that and in the course of two acts different truths emerge. No one is blameless and Solomon is right to warn against the opening of old wounds. Suchet dances between the lines, explaining the difference between value and price when it comes to the second-hand furniture business, leaving the moral echoing in the air; in the second act, when he vanishes for long periods, a lot of the energy and all of the humour leaves with him. But it is replaced by something else: a gladiatorial contest between the two brothers, where neither can emerge unscathed and where the whole nature of the capitalist dream, of the system that has warped both their lives comes under steady scrutiny.

It's quite verbose but the production, first seen at the Theatre Royal Bath, and directed with finesse by Jonathan Church never loses its grip. On Simon Higlett's cluttered set, at once a real attic and the symbolic repository of the broken and unwanted, Church often sets the brothers to one side, leaning against a wardrobe, or squaring up to each other across an occasional table. Sara Stewart, as Victor's disillusioned wife, watches on with quiet intensity, her sympathy switching – just as ours does – as each lays out his case.

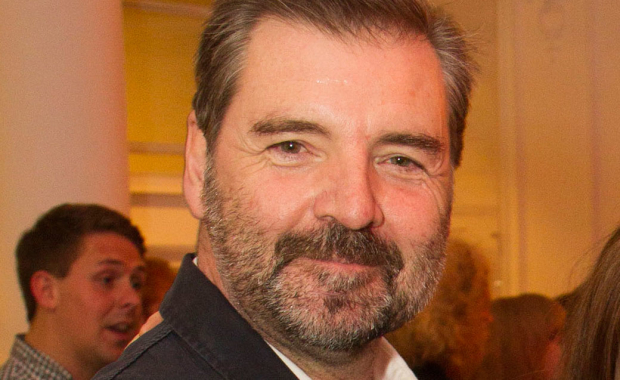

Stewart's is the hardest part, with the least to say and yet she brings subtlety and sympathy to the role of a woman who feels her own life has escaped her. Lukis is excellent too suggesting both Walter's fragility and his rage. As for Coyle, he gives a marvellous reminder of just what a good stage actor he is after years of being under-used in Downton Abbey. He conveys both warmth and integrity as Victor, his face constantly registering pleasure in small discoveries from his past, and doubt about his memories of it. But he finds the character's broiling anger, too, his sadness, his frustration and self-loathing.

The detail is so fine that it carries you through the wordiness; you believe in these people. What's more The Price's cry from the heart about a world where money rules and distorts all meaning feels more relevant now than ever. Miller's righteous anger about a system that crushes people by its moral failures seems less like idealistic preaching and more like a prescient reading of the nightly news.