Review: Othello (Liverpool Everyman)

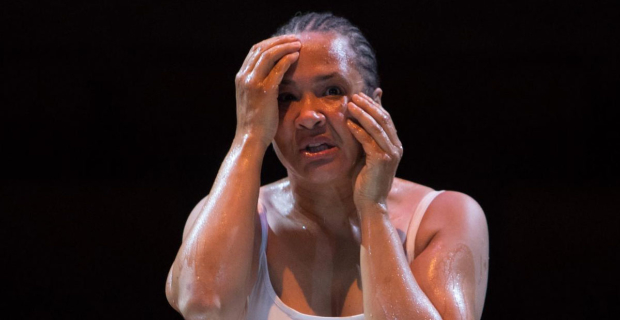

Golda Rosheuvel plays the titular tragic figure in Gemma Bodinetz’s production

© Jonathan Keenan

"The Moor". It's striking just how often Shakespeare's protagonist, in one of the Bard's most complex tragedies, is defined by the colour of his skin. In this new production at the Liverpool Everyman, Othello's race is not the only thing that singles out the lead amongst their peers.

Gender flipping in Shakespeare is hardly unknown, but Golda Rosheuvel's Othello is a different creation altogether. Not simply a male character played by a woman, her portrayal of the soldier casts her as a lesbian at the head of a mighty army populated by men. It's a bold move that could easily unravel but lends fascinating new inflections to a play first performed over 400 years ago.

Gemma Bodinetz's adaptation is the latest in the current season of the Everyman Rep, with an ensemble juggling roles and plays over four new productions. And while there's no crashing symbolism in Othello's gender swap, there are more intriguing dimensions afforded to a character whose otherness is intrinsic to the play.

Following a breakneck opening the tight cast settle into their roles – frequently juggled by a character – and costume-swapping ensemble. It's Patrick Brennan's Iago, vital to the mechanics and twisted heart of the play, who commands the attention initially. It's to his credit that only in the closing acts is Iago wholly unsympathetic. Meanwhile, the theatre-in-the-round setting makes the audience a co-conspirator to his plotting.

Marc Elliott as the hapless and lovelorn Roderigo finds plenty of humour. This Othello is placed in a modern-ish setting that sees characters wearing office lanyards; Elliott arrives in Cyprus wearing slip-on shoes and dragging a holdall, a gauche tourist out of his element and out of his depth. The bolshy interplay between Cerith Flinn's Cassio and a brassy Bianca, played by Leah Gould of the theatre's youth troupe, leaves an identifiably Liverpudlian stamp on the production.

Rosheuvel's Othello moves from easy confidence to suspicion and subsequently a picture of bitter betrayal and desolation. As Iago piles on sly rhetoric to manufactured coincidence, not to mention one of theatre's most famous false flags in the shape of a discarded handkerchief, Othello's trust in her spouse, as well as her mental health, are undermined.

© Jonathan Keenan

It's usual for an audience of this play to ask whether the character's insecurities over his race and class – and the prejudices that linger just beneath the surface of peers and subordinates alike – contribute to his swift unravelling. In this production those fractures are magnified and Rosheuvel's casting is what makes this Othello such a landmark production.

The marital bed of Othello and Desdemona that bears witness to the mayhem of the final act is shrouded in diaphanous gossamer as if to somehow protect the audience from the appalling acts contained within. When the union between the two reaches its terrible conclusion it's genuinely hard to watch.

Othello might be seen as typifying male misogyny – two men responding to perceived betrayals by their wives by killing them. But this new production throws it out of the window: is violence towards women born of gender, insecurity or power? Can the three ever be teased apart? Meanwhile Desdemona's father dies broken-hearted, bereft at the thought of his daughter marrying a Moor, a woman, or perhaps both.

Despite the fine work of Rosheuvel and Emily Hughes in the endgame, it's Patrick Brennan's Iago who leaves the lingering impression. Just why does Iago conspire to wreak such mayhem? Race? Gender? Sexuality? Bodinetz's production doesn't attempt explanations, nor does Brennan's portrayal offer any answers. Instead the audience is left to ponder fresh questions as to the motivation of one of Shakespeare's most enigmatic characters.