Review: Jellyfish (Bush Theatre)

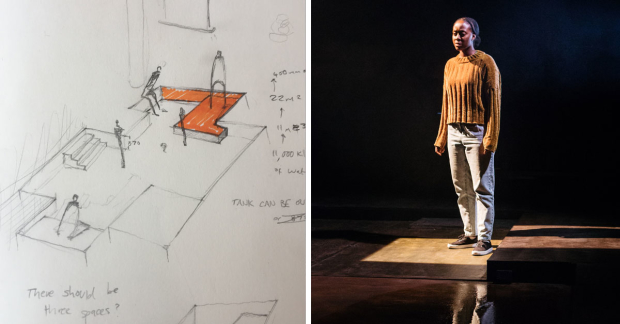

© Samuel Taylor

In Heartbreak, Craig Raine writes of a "mouth made for smiling a smile kept for kindness." In describing the facial features that come with Down Syndrome, he approaches the nature of the condition itself. As a disability, DS brings all manner of difficulties, but it's far from an obstacle to a happy life. Quite the opposite: DS finds delight in ways others don't. Ben Weatherill's Jellyfish, a deft portrait of what it is to live with Down Syndrome, draws out the dilemmas the condition brings with it.

At 27, Kelly (Sarah Gordy) still needs near-constant care – sometimes a helping hand, sometimes a watchful eye, sometimes just company. Her Down Syndrome has dominated most of her mother's life, and Agnes (Penny Layden) wears the strain of that in herself. She's "weathered," the script says, and you quickly see why: all the questions, the mood swings, the impulses to curb. Worry has worn this woman down, but, as Jellyfish shows, there's a fine line between mothering and smothering.

It's crossed when Kelly begins a relationship with a 32 year-old arcade worker named Neil. Ian Bonar's awkward introvert is, at first, uneasy: an able-bodied adult cosying up, cautiously, to a woman with DS feels taboo. Agnes would prefer Kelly dated someone more like herself, setting her up with someone on the spectrum, Nicky Priest's deadpan Dominic. Her daughter, however, knows her own mind – at least, to a certain extent.

That's the cornerstone of this tender play: How much agency and autonomy can those with intellectual disabilities really be granted? It's a difficult question with no right answers and Jellyfish raises the stakes as Kelly's relationship grows ever more serious. Each choice en route is mightily complex, as much for Agnes and Neil as Kelly herself. Weatherill covers a huge amount of ground – from the optics of disability to the unknowability of others – but Jellyfish never feels like an issue play. It's always human; drama couched in care.

Tim Hoare's simple staging lets the play speak frankly, never shying away from the realities of Down Syndrome. A mother shaves her daughter's legs in silence; that daughter strikes out at her mum in return. From that, Jellyfish finds room for laugh-out-loud humour: it affords neurodiverse actors agency up onstage. One scene, quietly groundbreaking, gives Gordy and Priest the stage to themselves for a comic conversation about the way they're coddled and perceived.

Set in Skegness, where hardship is the norm and the costs of care are a challenge, Jellyfish lets the seaside speak to Down Syndrome: a place of superficial fun and underlying sadness, where sweet teeth lead and impulses take over, just as Kelly craves ice-cream and kisses all the time. The arcade acknowledges the genetic gamble of DS, but a sign of Amy Cook's sandy set promises ‘A Prize Every Time.' It's a con only the most trusting take in – a mark of how easily Kelly steps into danger – but there's another truth in it too: All life's a gift.