Review: One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (Sheffield Crucible)

© Mark Douet

Dale Wasserman's 1963 play, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, followed close on the heels of Ken Kesey's iconic novel, more than a decade before the film which won Oscars for director Milos Forman and his two leading players, Jack Nicholson and Louise Fletcher. One of the few people to hate the film was Kesey. Wasserman's play – and Javaad Alipoor's Sheffield production – is much closer to his intentions, the latter even sometimes over-emphatic in fulfilling them.

The basic outline of novel, play and film is the same. Nurse Ratched rules her ward of a mental institution with an icy appearance of kindness, subjugating her weak-willed 'boys' to a set of rules that make life easier for her, over-ready to resort to electroconvulsive therapy and even lobotomy if any become obstreperous. Along comes Randle P McMurphy, small-time crook, who has got himself classified as a psychopath to avoid the prison farm as a punishment. He takes on "Big Nurse" by inciting the inmates to become individuals, free, with an anarchic sense of fun.

The differences between play and film are concerned with the balance between drama, even tragedy, and farce. There are crazy funny scenes in the play (watching the World Series without television, for example), but they are much shorter and relate more directly to Kesey/Wasserman's message.

© Mark Douet

The role of Chief Bromden, the giant Native American, is a major difference. The use as narrator of a character who pretends to be deaf and dumb and thus overhears all sorts of secrets was one of Kesey's sharpest inspirations and Wasserman carries that through with Bromden's meditations on The Combine which ruined his tribe and now pulses away controlling the inmates. Jeremy Proulx's bruised, tormented dignity suits the part perfectly.

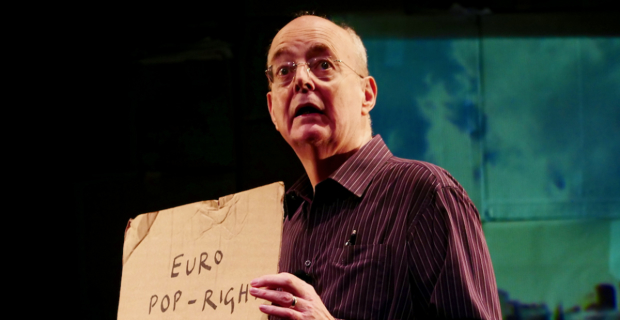

The major issue, however, is how much of a hero is Randle P McMurphy? Wasserman was furious when Kirk Douglas, in an early adaptation of his text, made him 'consistently lovable'. Of course he takes on an enemy who needs to be opposed, but his character is ambiguous and often unpleasant. Odious as she is, Nurse Ratched is correct when she accuses him of 'gambling with people's lives'. No one could find Joel Gillman's prancing, scuttling, singing, cackling McMurphy consistently lovable – a bit much early on, perhaps, but he places the character in a territory far removed from that of the movie hero.

This is a seriously thought through production, but one that can't quite resolve the inherent problem in Wasserman's play, the balance between the humanity and comic potential of the inmates. Also it could do with a touch more pace. It would be totally wrong to lay this at the door of Jenny Livsey, who stepped in at a day's notice to give a thoroughly believable account of Nurse Ratched, but the injury to Lucy Black, cast and rehearsed in the part, can't have helped. Carrying a script (which serves as clipboard or file), but using it sparingly, Livsey is especially successful in presenting the acceptable face of Ratched at first, then losing it step by step.

(© Sam Taylor)

Alipoor's production commands the vast Crucible stage with only a few sticks of furniture. There are strong performances all down the line from the inmates, notably Arthur Hughes' tremblingly, stammeringly mother-fixated virgin Billy Bibbit and Jack Tarlton's Harding, always trying to maintain dignity in the face of emotional and sexual inadequacy.

Lewis Gibson's soundscape, with its buzzing machines and bland music (Lawrence Welk, apparently), is key in establishing the world of the institution, though some later interventions veer towards melodrama.