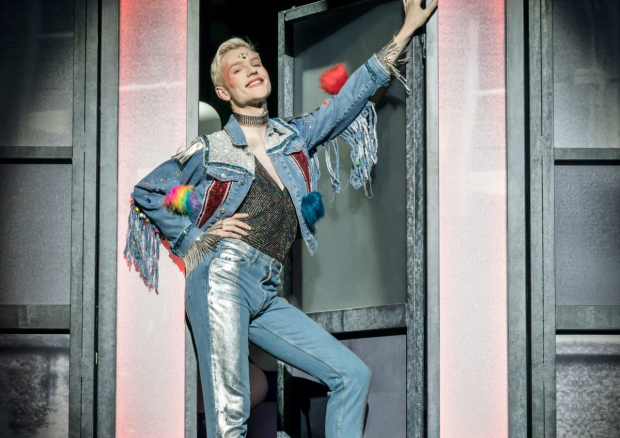

Review: Love and Information (Sheffield Crucible)

© The Other Richard

Six years is a long time in internet terms. Hell, even a day online can feel like a decade. Since Caryl Churchill's Love and Information premiered in 2012, the web has mutated to become monstrous, wondrous and strange. Where once there was fragmentation and Google, now there's fake news and rage. Caroline Steinbeis' revival, the first in the UK, reflects that new landscape by complicating Churchill's cut-up quickfire play. More than bombarding us with a series of miniature scenes, it shapeshifts in ways that give meaning the slip.

Churchill's play is designed to change with the times. It's a "Build A Bear" script: a pile of component parts that each staging must construct into a play anew. While its seven sections are set, the scenes within them can be shuffled into any order, played by any number of people and interpreted any way. They're full of echoes and overlaps, but it's up to each director (and each of us) to find meaning for ourselves – if, indeed, it can mean anything at all. Memory recurs, as do maths, dementia and war, but Steinbeis suggests that as information piles us, love falls away.

For its Royal Court premiere, James MacDonald put the play into a box and served its scenes straight. In a white, griddled square, scenes materialised like snapshots: a family Christmas, two friends on deckchairs, a woman taking tea. It ran like a slideshow, one scene then the next; like channel-hopping through time and space. The repetition of that – rat-a-tat-tat – made it relentless and rather dry: drama as data, too much to take in.

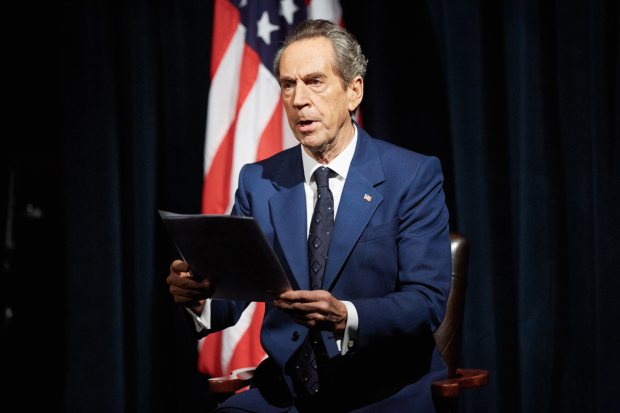

© The Other Richard

Steinbeis does much more to shuffle things up. Here scenes bleed into one another so that dogwalkers pass priests and Santa stomps through a jail. She splits images from dialogue, forcing us to decode what's really going on, and adds accents, songs and languages that add to the jumble. Everything's legible – but apropos of what?

Layers of performance make it more difficult to decipher. One argument plays out like a studio sitcom, Sule Rimi and Mercy Ojelade playing to the canned laughter of the crowd. Two lovers meet in a radio drama, actors in headphones performing these words. At one point, the whole thing tips into a kids' puppet show, where felt muppets discuss pain, marriage and emigration.

Elsewhere, registers shift: naturalism glitches into symbolism, dialogue into dance. Max Jones' grid stage lights up like the Stars and Stripes, then stands in for an art gallery for a long period of time. You're constantly working to work each thing out – let alone the overall scheme of the show – and it's brilliantly confounding, much like our world. Steinbeis doesn't simply show us the overload, she piles it on thick. You feel it. You live it. You race to keep up. And, in the process, you stop registering love.

A quicksilver cast handle its constant twists and about-turns, and Rimi's particularly strong when it comes to the churn. Frankly, I'm still not sure what to think of the play – whether it's conceit is genius or just superficial – but Churchill, being Churchill, writes with real aplomb. Every scene's a masterclass in dramatic economy, by turns crisply comic, awful or flat-out absurd. Whether it means anything or not, Steinbeis makes it feel like a mirror of our confusing world.