George Perrin: 'Everyone goes to Edinburgh hunting shows'

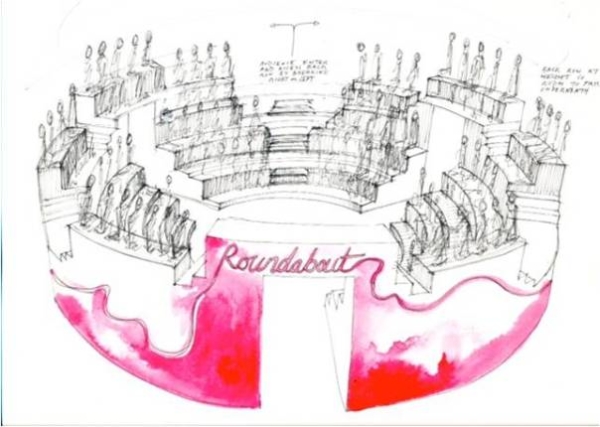

The co-artistic director of Paines Plough talks about the company’s pop-up Roundabout auditorium in Edinburgh and the Fringe as a place of discovery

How has the Roundabout auditorium been developed since the initial 2011-2012 season?

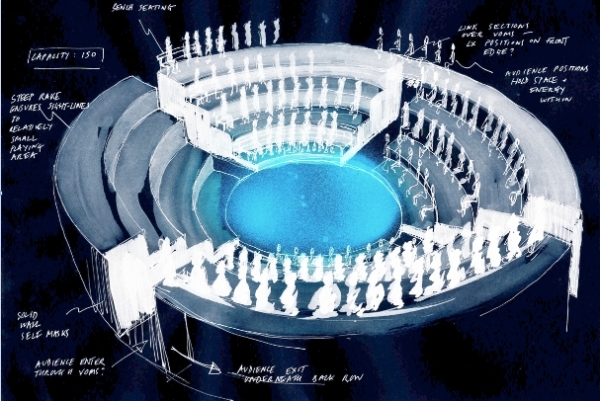

What we did in 2011 in Sheffield was a season of three plays in what we were calling the prototype of the auditorium. It was a scale model almost of what we intended ultimately to build. We put that in the Sheffield Crucible Studio to test out the architecture for that first season and then brought that to London in 2012 to Shoreditch Town Hall. That was a massive learning curve in terms of developing the structure and all the variables that we were trying to meet at the same time: capacity, footprint, stage dimensions versus seat depth and space for your feet, and then latterly in Shoreditch things like how we were going to light it, the kind of work we wanted to put in it and what plays worked best.

Those two years were real learning curves for us, and then we took 2013 to incorporate all that learning and bring a bit more expertise on board. We had that year of learning and redeveloping and redesigning, and then began work a few months ago on the final auditorium – or at least the first phase of it, which will open in Edinburgh this summer.

How did you decide which plays to include in the new Roundabout season?

The first three plays we did were Lungs by Duncan Macmillan, The Sound of Heavy Rain by Penelope Skinner and One Day When We Were Young by Nick Payne. Both Lungs and One Day When We Were Young already existed before we programmed them into the space and Penny’s play was written specifically for that group of actors. What we realised, whilst those plays were really successful and we were incredibly proud of them, is that the space is so idiosyncratic and so unique that when you’re writing for it it makes much more sense than if you’re trying to fit in a play that perhaps wasn’t written for that particular space.

So we took that on board when we were thinking about the season for this year. We brought Duncan’s play back just because it was so successful and it really does use the space in a perfect way so that the space supports the form of what he’s written. Dennis [Kelly]’s play was actually something that we developed with Half Moon Young People’s Theatre nearly ten years ago and Alex [Wood]’s play is a world premiere.

It was just a sense of the kind of plays that would work well in this space: plays that required a large amount of imaginative work on behalf of the audience, plays that were very narrative driven, plays that had a real theatrical playfulness at the heart of them – all of which work particularly well in the space. The space doesn’t support very literal naturalism particularly well; it’s much more like the Globe in the sense that you come on stage, say where you are and that’s where you are. It’s not a space that wants you to recreate, it wants you to leave space for the audience to fill in the gaps. Those were the loose guiding principles behind choosing the work.

What challenges are involved with staging work in this space?

There aren’t challenges per se that are any different to any time you work in-the-round. A lot of the craft that we’re discovering is required in the Roundabout is the craft of working in-the-round. It’s thinking about how you tell story when everybody’s got a different perspective; how you use image when people are looking at it in 3D rather than from one side; how you use traditional set pieces like furniture and props.

The strongest offer is text and actor, and where the text and the actors and the audience meet you don’t want anything else to get in the way of that. There’s a kind of purity to it, but as a result a real microscope on those elements. The actors are the only thing that are transporting you in Duncan’s play through a relationship of 60 years, and in Alex’s play across two continents, and in Dennis’s play conjuring a nine-foot troll. It’s those challenges, but they’re kind of brilliant challenges because they’re creative and performative challenges rather than practical and technical ones.

What do you think is special about the experience of watching theatre-in-the round?

The reason I love it – and I think this is so much to do with the fact that I grew up going to the Royal Exchange – is that I just think it allows the actors to play with each other much more than in a traditional end-on setting where you’re really concerned with how you arrange them pictorally. It’s more like you’re bringing an audience into a rehearsal room where they all sit round the edges and watch the work in in that raw, quite pure form that has always appealed to me. That aesthetic I find incredibly exciting and really accessible, and it really provokes me as an audience member to do a lot of work myself when I see that. That’s an exciting gesture for me and that’s something that I think the Roundabout holds.

How did your partnership with Northern Stage in Edinburgh come about?

When we take Roundabout on the road we’ll work with the local venues that we’re at to put other companies and work into the programme. We wanted to try that concept out at the same time as launching our work in the Roundabout, so Northern Stage were the perfect partners given that they were so actively programming younger companies into their main space. So Northern Stage have programmed the other four shows that are going to be in Roundabout each day. It was just a really harmonious fit between what they were looking for in terms of a second space to put more work into and the fact that we want Edinburgh to be a real testing ground for how we imagine Roundabout being when it’s on the road.

What do you think about the growth of curated programmes like yours and Northern Stage’s on the Edinburgh Fringe?

When we first started to come to Edinburgh with nabokov we took a lot of our shows to C Venues and we still had to apply, so presumably to some extent all the venues are curated. The difference for me in curation is if you’re actively seeking shows and buying them in.

But I wonder whether every venue is curated to some extent, it’s just curated from within the work that’s made available, and I suppose the Free Fringe is a bit of a response to that. We spent years and years trying to get into the Traverse programme and we never did with nabokov, although nabokov has recently under Joe [Murphy]. That always felt like a real achievement if we could get into that Traverse programme, but actually now that doesn’t feel like the be all and end all.

Do you think it’s still possible to truly discover unknown work in Edinburgh?

I swear by the fact that it’s impossible to have a brilliant show in Edinburgh and it be unnoticed. I’m convinced of it. The approach that I notice amongst my peers when they go to Edinburgh versus when they’re week by week in Manchester or London or wherever is so different. Everyone goes to Edinburgh hunting shows. I think it’s really hard to have a brilliant show in Edinburgh and for nobody to know about it, because the speed of the word of mouth and the drive that everyone has to find the hit show that isn’t the obvious hit show means that the good ones rise to the top.

We spent so much money in the early days of running nabokov taking shows to Edinburgh and every year we’d think "is this really worth it?", but I still think it’s such a brilliant showcase. People will go and see shows in tiny Fringe venues in Edinburgh on the same day that they go and see something at the Traverse in a way that I just don’t think happens on the London Fringe and Manchester Fringe outside of festival time. I do still think it’s a brilliant place to take a new piece of work and get noticed and get higher profile support than you would anywhere else in the country at any other time.

FOR MORE ON EDINBURGH 2014 VISIT WHATSONSTAGE.COM/EDINBURGH-FESTIVAL