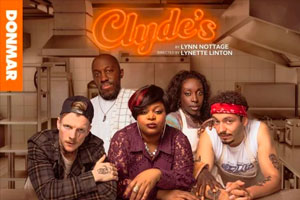

Clyde’s at the Donmar Warehouse – review

The European premiere of Lynn Nottage’s Sweat sequel runs until 2 December

There are few finer writers working in contemporary American theatre than Lynn Nottage, and perhaps nobody that chronicles the tragedies and triumphs of working-class people with such steely compassion and bracing humour, whose dialogue finds the potty-mouthed poetry in sometimes very challenging lives. The 2018 Donmar production of Sweat, her searing drama about the declining fortunes of a group of female factory workers in the Rust Belt region of the USA, suggested that in director Lynette Linton, Nottage had found the ideal British interpreter of her work. That impression is further reinforced now by Linton’s gritty but gorgeous staging of Clyde’s, first seen on Broadway in a different production in late 2021.

Clyde’s is a less abrasive play than its predecessor, driven more by dialogue, storytelling and delightful characters than plot, but it’s set in the same Berks County area of industrial Pennsylvania. Specifically, it unfolds in the rundown kitchen of Clyde’s road-stop sandwich shop, where the workers are all fresh out of jail. Frankie Bradshaw’s hyper-realistic set, with apron-clad humans scurrying about beneath panels of garish neon, seems pretty straightforward at first but clues and hints in Oliver Fenwick’s lighting and the sound design by George Dennis subtly suggest this might be a sort of purgatory, a holding space for a selection of souls in limbo, happily not still incarcerated but also not yet fully integrated back into society.

This production reunites Linton with two cast members from Blues for an Alabama Sky, her acclaimed National Theatre debut last year: Ronkẹ Adékọluẹ́jọ́h and Giles Terera are barely recognisable, but just as wonderful, here. Adékọluẹ́jọ́ is mesmerising as Letitia, whose motor-mouthed vitality and love of the spotlight belies a back story of deprivation and the pressures of being a single parent to a youngster in constant need of care. This rising star is a natural clown, with a dancer’s physicality and an ability to turn to heartbreak on a dime. She’s utterly terrific.

Terera plays the saintly Montrellous, described as “like Buddha if he’d grown up in the hood”, a charismatic, calming presence and sandwich-making connoisseur (a lovely conceit of Nottage’s script is having the workers intone their sandwich recipes as a sort of workplace ritual, and some of them sound mouthwatering). Terera gives Montrellous a simmering energy and warmth that makes it all the more moving when he finally reveals the reason for his stint in jail. Interestingly, he’s the only staff member who can stand up to the fearsome boss Clyde.

Who then is Clyde, the blingy, trash-talking, chain-smoking, power-dressing lady boss who has her employees cowering in fear? Why does she never eat?! One of the workers describes her as being like a licensed dominatrix, to which Letitia replies: “I heard her husband changed the safe word, but she couldn’t remember it.” If Montrellous is like a guardian angel to his colleagues, then does that make Clyde the Devil Incarnate? She’s certainly a piece of work, her business clearly in thrall to some dangerous high rollers.

Nottage lets us see her sexually harassing a new staff member and engage in some nasty anti-immigrant ranting aimed at deceptively sensitive Hispanic worker Rafael (Sebastian Orozco, delivering a memorable combination of mouthy street-wise swagger and heart-piercing vulnerability) but it feels more like misjudged horseplay than genuine malevolence. At least, that’s how it comes across in Gbemisola Ikumelo’s performance which is full of comic zest and eye-rolling spite but never feels truly nasty enough. When she says “I’m not indifferent to suffering, but I don’t do pity”, it rings entirely true, but the abject panic she inspires in her staff doesn’t quite: she has presence but she verges on the endearing with her villainous laugh and whipsmart putdowns.

This sense that the characters don’t have too many life options right now beyond this airy but grubby cookhouse, gives their exchanged stories and aspirations an extra poignancy and urgency. Nottage’s language is muscular, vibrant and gloriously funny, the tonal shifts into more delicate, heartfelt territories as layers are stripped away from each of her people happening seamlessly under Linton’s guidance. The energy and focus never dip for a moment, not even in the swirling, scene transitions (outstanding movement direction by Kane Husbands) which have a dream-like quality as sections of the play bleed into each other.

Patrick Gibson’s Jason, with his racist facial tattoos, air of aggressive resentment and highly questionable attitude to hygiene, is the newest member of the kitchen team and watching the barriers break down between him and his initially sceptical new co-workers is a thing of spiky joy. Gibson manages Jason’s partial transformation with forensic precision and irresistible comic skill.

The overall impression of Clyde’s is that of a humane genius manipulating a colourful gallery of lovingly drawn, sometimes outrageous characters through a battle of good versus evil. It meanders a bit, but it’s never dull. This is a vivid, life-enhancing play, full of heart, hope and humour, that suggests that whatever life throws at people, they can and will, if they cling on tenaciously enough, travel through to the next, better stage of human existence. Linton’s production is a real beauty. You’ll come out beaming…and possibly craving a really excellent sandwich.