Review: A Christmas Carol (The Old Vic)

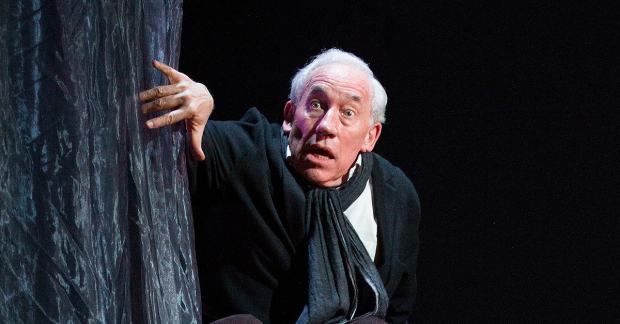

© Manuel Harlan

Ah, Ebenezer Scrooge. There he is at home on Christmas Eve, quietly minding his money, shutting his door in the faces of carol-singers and proclaiming "bah, humbug" to anyone who will listen. Only then, in what must surely constitute one of literature's busiest nights of haunting, to be visited by no fewer than four ghosts, and learn a moral lesson about social division and the meaning of Christmas that will echo forever down the centuries.

Goodness, no wonder the man's so grumpy; it's exhausting just thinking about it.

Anyway, we all know the story, and here it is at the Old Vic for a second year, in a sparkling, atmospheric reimagining written by Jack Thorne and directed by Matthew Warchus.

Stephen Tompkinson takes up the role of the Grumpy One, stepping into the hobnail boots vacated by Rhys Ifans. A strong ensemble cast divides up the rest of the characters between them, and shares the voice of Dickens's narrator – more or less a proxy for Dickens himself, who wrote the 1843 novella in a frenzy of indignation about poverty and the upper classes' lack of compassion.

The action zips along – each act lasts only around fifty minutes, making this an ideal festive outing for restive children. Officially, it is recommended for those aged eight and above, perhaps because the sound and lighting, expertly designed by Hugh Vanstone and Simon Baker, manage to make the appearance of the ghosts quite genuinely frightening – at least for this thirtysomething, but not, apparently, for the six year-old boy in the next row, who declared himself not in the least afraid.

Tompkinson makes an excellent Scrooge, his long frame crouched and stooped in the early scenes, perhaps by the weight of all that money and misery. By the end, the scales of selfishness dropped from his eyes, he stands tall and light-footed, and skips across the set – beautifully designed by Rob Howell, with a thrust bisecting the stalls, and several rows of seats positioned on the stage (it's worth trying to bag one of these if you can, if only for the rare actor's-eye view of the auditorium).

Tompkinson is skilled, too, at emphasising the deeper psychological aspects of the character, as does Thorne's script – we are reminded, in this production, that this is as much the story of an older man looking back over his life, and trying to make peace with his mistakes, as it is that of an unreconstituted miser forced to confront the error of his ways.

The strongest message here, though – true to Dickens's original aim, and unfortunately no less resonant 176 years on – is that no man or woman is an island, and we cannot afford to ignore the suffering of those around d us.

It's hard to imagine a more pertinent Christmas tale, delivered with greater atmosphere, theatricality and emotional heft. Sorry, Scrooge – you're going to be rudely awakened on a few more Christmas Eves yet – but it'll be worth it, I promise.