Studio theatres are where you'll find the next James Corden

© Johan Persson

Theatre is a blink-and-you-miss-it medium; always has been, always will be. Performances vanish, but so do performers. They age. They change. They move on to other things – often bigger, not always better.

The other week, I watched a recording of A Respectable Wedding, Joe Hill-Gibbins‘ 2008 production at the Young Vic. It’s grainy and single-shot. The colour's a bit off and the camera’s too far away. You can’t make out the faces of those onstage. You get the gist, but not much more. You can see the joke when the audience laugh, but, on a tiny laptop screen, alone, ten years later, you can’t laugh along. What was funny there and then isn’t here and now. The magic has gone. The spell’s been broken. You can see the show, but it’s over, it’s done, and it’s never coming back to life.

One of the unique privileges of theatre is the chance to see great actors up-close

In the midst of it though, there’s a familiar tummy. It comes with a soft London accent and a volcanic laugh. They belong to one of the most famous faces on television today: one James Kimberley Corden. Next to him, for good measure, there’s Russell Tovey and Jemima Rooper.

This was a month before Gavin and Stacey got started on BBC Three; a month before Corden’s star really started to rise. He was a History Boy by this point, sure, and a Fat Friend before that, but, still short of 30, he wasn’t yet tipped to go right to the top. And here he was, acting on a tiny stage in a small studio theatre, just off The Cut. James Corden playing to an audience of 150. You won’t find him doing that these days.

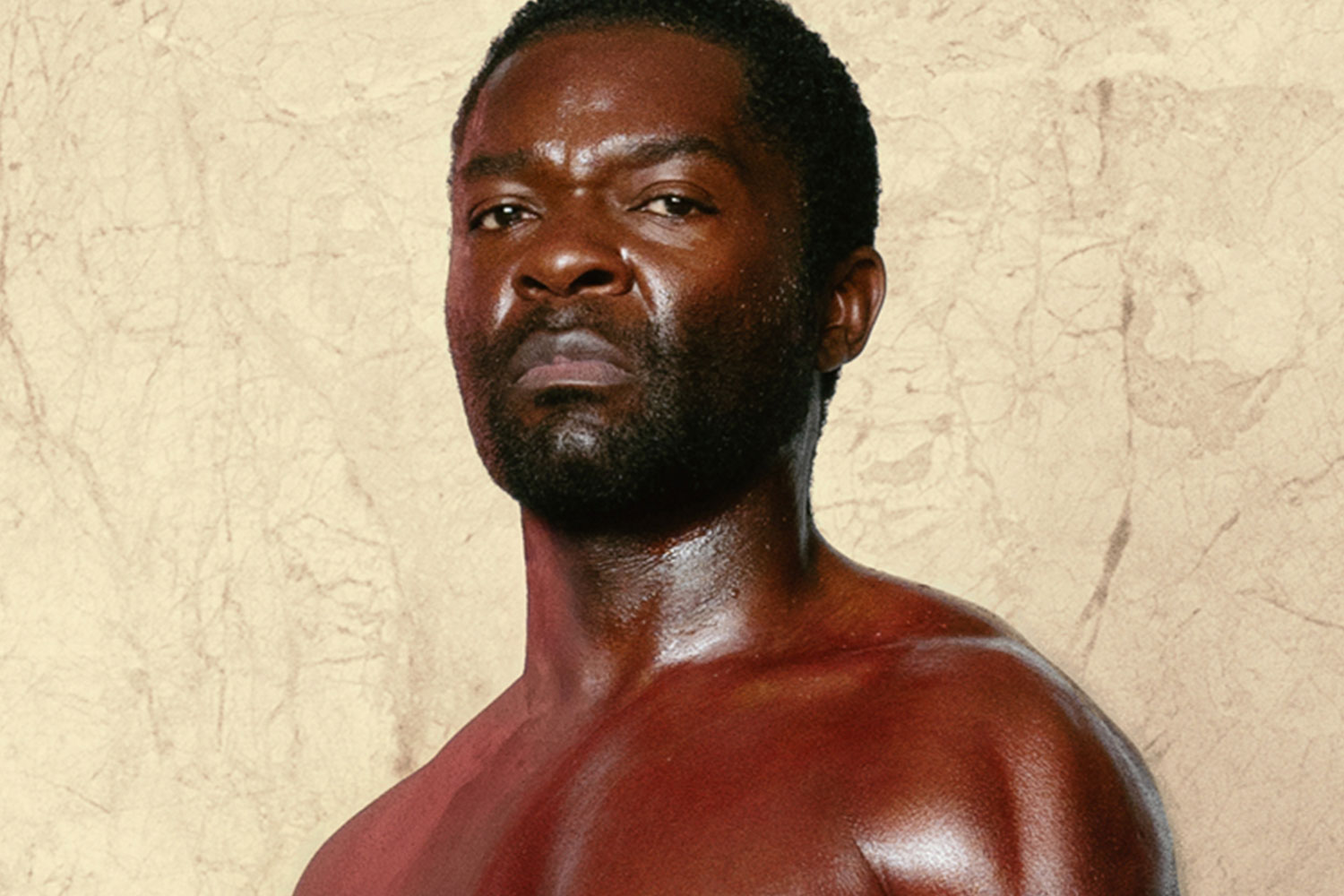

In a sense, Damien Lewis is wasted on a 150-seater

Isn’t this one of the unique privileges of theatre? The chance to see great actors up-close. There’s a lot to be said for bombast and power, for letting Chiwetel Ejiofor loose on a big stage or having Ruth Wilson eyeball a large crowd, but given the choice I’d plump for the intimacy of a small space every time. It’s there that you get to zoom in on their choices, the tiny traits that make a character tick. Actors ease into small spaces. They don’t do battle with them or hide behind technique. They let us see who they really are. In small spaces, acting feels like a two-way thing.

It’s a privilege to watch a great performance at close quarters – all the more precious because so few people get to see it. Some of my keenest theatre memories come from small spaces: Andrew Scott unleashing Sea Wall at the old Bush, making this tiny room fall still or Ben Whishaw and Katherine Parkinson circling one another in Mike Bartlett’s Cock, spiralling into sexual desire.

Small spaces offer the chance to see great actors up-close before they take off

Too often, however, great actors leave studio theatres behind them. They grow too big for them, not as artists, but as stars. In a sense, Damien Lewis is wasted on a 150-seater. He can pull people in, attract new audiences to the art-form, but not if there aren’t seats available.

It does occasionally happen. The right part in the right play can bring a big name back to a small space. Jez Butterworth’s eerie three-hander The River hooked Dominic West for the Royal Court Upstairs. Sometimes the right theatre can do it. It was only a matter of time before Mark Rylance returned to the Globe to try the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse for size – and what a revelation that was. Within five minutes of Farinelli and the King, he’d locked eyes, momentarily, with everyone in the room; an invitation to play. The Donmar Warehouse and the Almeida, special spaces both, can attract established talent.

Studio theatres are breeding grounds for brilliance

But talent doesn’t become talent just because it takes off. Recognition isn’t a prerequisite for brilliance, but, more often, a result of it. James Corden was James Corden before he was ‘James Corden’ – still a belly laugh presence. You can spot his impact and his energy in A Respectable Wedding, even squinting at it on a small screen. He injects the whole thing with a particular humour. He lets the production laugh at itself.

This is what small spaces offer then: the chance to see great actors up-close before they take off. It’s a unique opportunity. Studio theatres are breeding grounds for brilliance and they’re flush-full of great performances. Right now, take your pick. Erin Doherty’s in Wish List at the Royal Court Upstairs, and you can see the way she smudges every sentence, finding tiny fudges of anxiety. Or watch Joan Iyiola in The Convert at the Gate – a performance that manages to be both flirtatious and feminist, even as it disintegrates into alcohol dependency. Or keep your eyes on Nicholas le Prevost as he slides into something sinister over the course of Winter Solstice at the Orange Tree. They won’t be there for long. Blink and you’ll miss them – and no recording in the world will do them justice.