Review: Hedda Gabler (Lyttelton, National Theatre)

It is quite a gift to make a play as familiar as Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler feel completely unexpected. But as he showed with A View from the Bridge, director Ivo van Hove‘s great talent is to make every play a play for today. This is not an act of historical reconstruction but a radical rethinking so gripping that you find yourself leaning in, listening to nuance, wondering what exactly happens next.

Every single thing about it is both tough-minded and surprising. Jan Versweyveld’s set is not some genteel drawing room, but a sparsely furnished white box, an apartment that has perhaps seen better days. Patrick Marber‘s new translation is supple, spare and funny; close to the original but with just enough modernity to let him highlight both the humour and the threat.

Joni Mitchell‘s "Blue" plays between scenes, an undercurrent to Hedda’s aching ennui. She becomes the ultimate desperate housewife, a woman who literally doesn’t know what to do with herself or all her dreams and ambitions, flicking the blinds or stapling dead flowers to the wall just to have something to do with her time and her life.

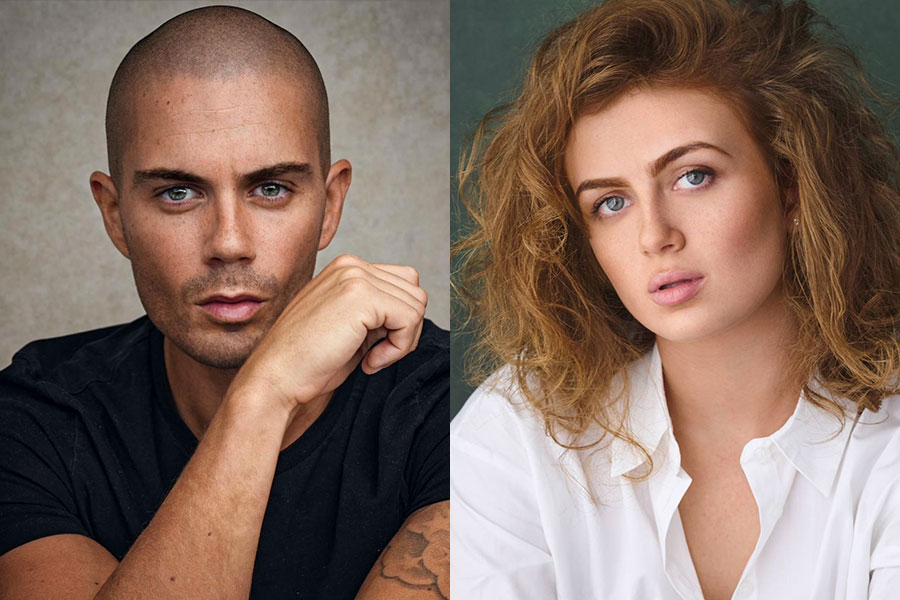

Her destructive qualities slither out of that sense that her only calling is to be "bored to death." She is unhinged by it. In Ruth Wilson‘s superb, subtle performance, she barely knows what she will do from moment to moment. We first see her slumped over her piano, picking out a half-tune; she sits with her boring husband Tesman like a stuffed doll, playing the good wife; when Judge Brack plays his games of seduction, she shies away like a frightened horse. Describing her courtship by Tesman she imbues the word "academic" with contempt and loathing.

But her principle loathing is reserved for herself. It is the word "courage" and her sense that she ultimately lacks it that makes her taunt her former lover Lovborg (Chukwudi Iwuji), tempting him to drink, in order to feel her own power and drive him to destruction. The word runs through the text like a plaint; it is what Thea has and what Hedda so singularly fails to display; Thea may be a mouse but she is prepared to leave her husband and give everything up for Lovborg and for love. Hedda settles for marriage because she is scared.

Van Hove picks away at the text, searching for clues, weaving conclusions: when Hedda hears Thea and Lovborg talking about the manuscript of his masterpiece, describing it as their child, she instinctively touches her stomach. Her destruction of the manuscript, which makes her punch the air in triumph, prefigures her own self-destruction – and that of the child she is most probably carrying.

But the thoughtful reassessment of what everybody in the play is doing affects every character. Kyle Soller’s Tessman isn’t a desiccated stick, but an ambitious young lecturer, ready to make his way in the world; Sinead Matthews makes Thea nervously unable to believe her own bravery but determined to fulfil her purpose; Kate Duchene’s Aunt Juliana is genuinely decent, prepared to do good; Rafe Spall‘s Judge Brack by contrast is not a charming seducer but a dangerous blackmailer, a man who enjoys and exercises power with no sense of moral scruple.

It is a dark and unusual vision, and produces a Hedda unlike any I have ever seen, devastating in its impact, a play full of pain and doubt.

Hedda Gabler runs at the National Theatre until 21 March 2017.