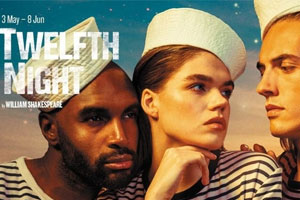

Twelfth Night at Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre – review

The Mediterranean-infused staging runs until 8 June

Owen Horsley’s Twelfth Night would make a good first Twelfth Night: though without really giddy romance, it steers away from some of the more well-trodden innuendos, and prizes certain more unusual things about the play to quiet and steady effect. It finds an understanding and well-used space at Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre to unwrap unhurriedly. It’s a dignifiedly twilight world, stylish and welcoming.

We only see the converse of the neon sign advertising Olivia’s self-titled nightclub, facing away from us: fittingly, as Anna Francolini’s Olivia, who dominates this production, is a behind-the-scenes weirdo in the most winning way. Grief has made her a little funny, marinating in her own company and that of those who indulge her, clinging to the sequinned urn of her late brother. Her every movement is a bit too pointy and clawy. She’s eminently loveable in her coiffed red halo (wigs, hair and makeup smartly designed by Carole Hancock), with Ryan Dawson Laight’s pouty costumes for her making great, over-exuberant use of mesh.

Evelyn Miller is a very upright, sweet, open Viola (able to be very funny in her almost-fight with Sir Andrew Aguecheek, the gormless, charming Matthew Spencer): you see why Olivia can’t quite resist the air of appealing frankness about her.

And it really does feel like a household, if not that much like a messy gay club, the kind to have a drag queen like Sir Toby Belch (Michael Matus). His get-ups are just this side of outsize, and Matus is funniest when duping others alone, turning Viola and Sir Andrew against each other in quickfire sarcasm (with the help of Jon Trenchard’s ‘Fab Ian’). Twelfth Night always feels crowded for the comic spotlight, and Julie Legrand’s Feste is an imperious fool in possession of himself, while Spencer’s Sir Andrew is a soft plasticine model of a man, and Anita Reynolds’ Maria is the sharpest and driest of the lot.

Olivia’s club is thus well staffed, and it does feel like a place people are blown into and out of, comfortably, with a turn into a more sultry night mode after the first half’s warmth, well-managed by Aideen Malone’s lighting design. Sam Kenyon’s gentle, cabaret-style songs slip smoothly throughout the production, offering Legrand and Francolini ample opportunity to beguile. Sailors and chanteuses don’t feel a natural stylistic match, but set designer Basia Bińkowska’s dusty blue interior uses the space beautifully: actors are well found within it. Perhaps Sir Toby’s appetisingly brash design promises something the rest of the production doesn’t deliver: the scenes are clean and light, just as they look.

Richard Cant’s Malvolio is a hilarious unhappy fit, self-pleasingly wrapped up in himself, his movements so prim, “practising behavior to his own shadow”. You can see why they go for him, and the production wants us to sit with the injustice and indignation of the cruelty, though he struggles a little in joining the dots of his relationship with Feste as he mocks him, and in Malvolio’s silent homecoming at the end; it feels as if there’s just a couple of moments missing.

The straight romances (and they do feel straight here, with little orientation-questioning confusion) feel somewhat minimised, as if they aren’t where the show’s heart seems to lie. Though Raphael Bushay’s Orsino is in fine petulant fettle early on, he and Viola’s moments together aren’t given the scope to make the breath catch when they come to realise they can be together, once her identity is revealed, so the Duke’s spurned misogyny feels like his main note.

Sebastian (Andro Cowperthwaite) and Antonio (Nicholas Karimi) are given a real, lasting romance which feels both wise, and as if it glosses with a shrug over Sebastian’s obliging attitude towards marrying Olivia at first meeting, eschewing messier explanations to dig for. But the humour and pathos of the end it locates Olivia in is almost worth it: we leave her resigned, certainly humiliated, but still dignified, and not quite alone.