The White Factory at Marylebone Theatre – review

Maxim Didenko’s world premiere production runs until 4 November

As the cancerous Nazi regime began its insidious spread across Poland, the Łódź Ghetto, under the leadership of its Jewish Elder Chaim Rumkowski, attempted to make its occupants indispensable to the Nazis by way of setting everybody to work and creating a “city of productivity”. By the time the war was in full swing, there were 150 factories all at work, including a converted church that made feather-stuffed pillows – the White Factory of the title. As much as this may have been assisting the German war effort, it was believed they’d also be preserving their lives.

Russian-born Dmitry Glukhovsky has written a fascinating piece of theatre that uses a combination of historical and fictionalised characters to tell this extraordinary and devastating story in a grounded translation by Marian Schwartz. Director Maxim Didenko brings it all to vivid life with some startling imagery and bracing brutality.

Yousef Kaufman (powerfully played by Mark Quarterly) is a young Jewish lawyer who rails against the discrimination that he is shown as the war approaches. His determination to leave Poland with his wife (an affecting Pearl Chanda) and two young sons is thwarted and they find themselves trapped within the new order.

Adrain Schiller’s nicely contradictory Rumkowski is neither played for heroics nor villainy and is given a warts-and-all treatment that demonstrates a level of desperation befitting a man who was negotiating with mad men and was only ever offsetting one evil with another, whilst never quite halting the inevitability of the appalling finality of what was to come.

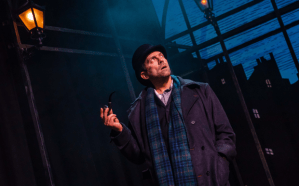

As the local Commander of the Nazis, James Garnon brings chilling life to Wilhelm Koppe. His unsettling stillness makes the evil that courses through him all the more disturbing. As he gazes over the thick forests that neighbour the city, he casually hints at the plans afoot for the building of concentration camps and how well the forest will disguise what is really happening. It’s a haunting moment that hangs in the air with suitable menace. At Koppe’s right hand is the equally minacious Mordhke, played with a brutish terror by Matthew Spencer.

Whilst the text can meander on occasions and the first act in particular would benefit from some more focus, there are moments that hit home with devastating power. Schiller quietly and purposefully delivers the speech of Rumkowski’s in which he asks of his own people to hand over their children to send to their deaths – nicely delivered and terrible to watch. But Koppe’s subsequent trial, having been discovered working in a chocolate factory much later in 1960, is given more brevity than it perhaps deserves.

Galya Solodovinikova creates some unflinching and heart-stopping moments with a simple yet effective stage design. The sterility of the white box set is given moments of powerful impact with mounds of burnt ash to depict the growing death toll as well as blood spatter breaking the icy claustrophobia. Some bold use of projection with some interesting video work by Oleg Mikhailov along with some brooding underscoring by Louis Lebee all add to the tension.

This is brave and exciting work from the relatively new Marylebone Theatre and is definitely worth a trip out of the West End for a visit.