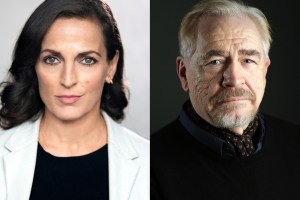

The Score starring Brian Cox at Theatre Royal Bath – review

Trevor Nunn’s production runs until 28 October

It’s a reunion of former National Theatre directors down in Bath at the moment. Following Richard Eyre’s snoozy A Voyage Round My Father, we now have Trevor Nunn’s production of actor and scribe Oliver Cotton’s The Score, a solid, sometimes stolid work that follows the latter years of the great Johann Sebastian Bach. The man is brought to convincing life by the draw of the night, Brian Cox, returning to the stage after his Emmy-nominated work on Succession.

Cotton’s play concentrates on a real-life documented meeting between Bach and King Frederick the Great that happened on 7 May 1747, which produced one of Bach’s great late works, The Musical Offering. Visiting his court musician son Carl, Bach was challenged by the King to improvise a fugue in three parts based on a theme the King gave him, after successfully passing this test, he was challenged to extend to six, which eventually led to his collection of work that Charles Rosen described as the most significant piano composition in history.

Cotton uses this meeting, and the evening’s high point is undoubtedly the build to a genius in full flow, to explore Bach’s religious beliefs and how his beliefs in the scriptures could clash with an artistic but power-hungry King who is challenged in a couple of heated debates around the actions of his soldiers in the Silesian War. As the nightly news recaps atrocity after atrocity, and some try to justify it based on a strip of land, the debates take on a more charged and topical theme.

Nunn’s production is stereotypically stately and reliably realised. Its first half slowly sets things up as we are introduced to each of the central characters in a series of long talky scenes, and then come alive in the second half as wagers are waged and ideas are debated by the artist and the king. Yet it’s a long evening, close to three hours in length, which sets up 15 minutes of fully charged theatre. The rest of the night ambles along pleasantly but without any real vitality.

However, for many, the night will be worth it to see Cox, returning to the stage after his late career triumph as Logan Roy. A few months before he plays the Tyrone patriarch in A Long Day’s Journey Into Night in the West End, his Bach is another mammoth part to essay, rarely leaving the stage and always the fulcrum of the evening. His is a quieter, more reflective presence than the monstrous Roy, kind in his wholesome praise of others, deeply in love with his wife (played by his real-life spouse Nicole Ansari-Cox) carefully charting his way through a sentence to ensure he is crystal clear in his clarity. It is only when he is pushed too far in the court and directly confronts his King that we see that bottled-up anger that Cox releases in an oratory of passion. A line stumble here or there suggests the marathon he is undertaking, but it’s a performance that demonstrates we are lucky to have him back on our stages.

In a night so focused on Cox, the other performances are mostly embellishments though Stephen Hagan’s King balances the artist and the warmonger (his portrait resided in Hitler’s bunker as an inspiration to the failed artist turned Führer) while Peter de Jersey’s Voltaire feels airlifted in from another show, full of extravagant flourishes and ‘Allo ‘Allo! accent as the superstar philosopher. Robert Jones’ sets are typically grand moving us between the modest surroundings of the composer’s home and the palatial grandness of the King’s residence. Ultimately, Cotton has produced a star-driven play, one that its leading man avails himself well in, without fully hitting the peaks that etch itself on the memory bank.