WhatsOnStage’s London-based critic Sarah Crompton has picked her favourite shows of 2025 – a smorgasbord of new plays, classic revivals, musicals and more. In a year for a theatre community finding its place in a turbulent century, which of these do you agree with?

It’s been a fascinating year in theatre, and as I draw up my list of favourites, I’m as usual conscious of all the plays I’ve missed seeing as well as all those I’ve enjoyed. I hope to catch some of those – Punch by James Graham, the RSC’s Kyoto, and Roy Williams’ adaptation of The Lonely Londoners when then they are revived next year. For now, these are the nights of 2024 that have stayed with me most vividly.

Yaël Farber’s production was a long, dark slog – but it was also one of the clearest and most thoughtful productions of King Lear I’ve ever seen. Danny Sapani’s Lear was ferocious, managing to suggest both a domestic and public tyrant and a man who fears he might be making some terrible decisions. His daughters – Gloria Obianyo, Akiya Henry, Faith Omole – all convinced as a family struggling with domestic violence. But best of all was the way Farber treated Clark Peters’ Fool, putting his quiet presence at the heart of the play like a ghost of wisdom.

9. The Cabinet Minister, Menier Chocolate Factory

I didn’t review Nancy Carroll’s adaptation of Arthur Wing Pinero’s 1890 comedy about a cabinet minister accused of corruption and his shopaholic wife because Carroll is a friend. But I was thrilled when it entranced audiences and critics, with Carroll praised not only for her biting adaption but for her beautiful performance as the silly but appealing Kitty. Farce is such a difficult genre to bring off and yet the entire cast managed to walk its tightrope with aplomb. That it opened amidst the furore about the Labour party accepting gifts, and was running when the great Maggie Smith, one of the most brilliant farceurs, died made it seem all the more relevant.

David Byrne’s time as artistic director of the Royal Court has begun with terrific confidence mixing the experimental (Bluets), the unusual (Brace, Brace) and the old school in the form of this first play by the director Mark Rosenblatt, about Roald Dahl and his antisemitic views. It was bold, bracing, and intensely relevant, revealing the way in which Dahl’s defence of the Palestinians during into the 1982 Lebanon war hardened into something more ugly. It also featured an extraordinary central performance from John Lithgow making Dahl into a monster of immense charm, ably supported by Elliot Levey, Romola Garai and Rachael Stirling, with direction by Nicholas Hytner who like Lithgow, was making a belated Royal Court debut.

7. Fiddler on the Roof, Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre

In the episode of the WhatsOnStage Podcast that accompanies this piece, our editor in chief Alex Wood steals this off me as one of his choices. It was perhaps the surprise of the year, utterly revelatory in the directness and simplicity of director Jordan Fein’s approach. The set, by Tom Scutt, which sheltered the villagers under a curved ramp covered in corn, was perhaps my favourite of the year; the moment when Teve’s daughter Chava played her clarinet alongside the fiddler as she leaves her home for good was staggeringly emotional. The whole thing was a glory.

6. = Oedipus, Wyndham’s Theatre

A play from the past became a text for the ages in Robert Icke’s searing contemporary adaptation of Sophocles. It presented Mark Strong’s Oedipus as a confident, strong politician on the verge of a huge election night victory and then allowed his over-confident obsession with finding out the truth to strip him of everything, leaving him huddled on the floor. Icke’s taut staging, marked by clock ticking down to the exact moment of revelation, was driven by a series of powerful performances, particularly Lesley Manville’s Jocasta and June Watson’s Merope, both wound like springs with the suppressed knowledge of a terrible past.

6. = The Other Place, National Theatre

Just when you thought you’d seen the definitive Greek tragedy of the year, another arrived to challenge its ability to make human suffering speak down the ages. Alexander Zeldin’s version of the Antigone story turned an epic of burial and battle into a family saga of concealed secrets and terrible, overwhelming grief. It was almost unbearable in the neediness and profound sadness it uncovered, brought to devastating life by a cast led by Tobias Menzies and Emma D’Arcy. As in Oedipus, there were gasps as the plot unfurled – a tribute to the vitality of the stories and their adaptations by two of today’s most brilliant writers and directors.

Listen to Crompton and managing editor Alex Wood discuss their picks below:

5. Waiting for Godot, Theatre Royal Haymarket

Another shock. Director James Macdonald treated Samuel Beckett’s 1953 drama not as a masterpiece, or as the play that changed theatre for ever, but simply as a brilliant play and directed it with such sensitivity and tenderness that new insights gradually emerged. Helped by the perfect pairing of Lucian Msamati as a pragmatic Gogo and Ben Whishaw as a wistful Didi, the production found the love and endurance at the heart of a tale of pointless waiting.

4. Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812, Donmar Warehouse

The best new musical of the year came in its closing days when Dave Malloy’s witty, luminous riff on 70 pages of War and Peace finally got a UK premiere. Directed by Timothy Sheader, in his first production as artistic director of the Donmar, it’s a remarkable mixture of sophistication, high emotion, glorious songs, and deep silliness. The opening number which labels the key players – Natasha (young), Sonya (good), Anatole (hot) – is glorious funny; the close when Pierre sees the great comet in the title and realises what it means to him, profoundly moving. Unbelievably well-sung by the entire cast, it’s absolute knockout.

3. Dear Octopus, National Theatre

The director Emily Burns has had a remarkably good year; her production of Love’s Labour’s Lost which opened the tenure of Tamara Harvey and Daniel Evans at the Royal Shakespeare Company was a model of clarity and good fun. And her revival of Dodie Smith’s 1938 play about the Randolph family – not seen in London for 50 years – was an utter revelation. This was a play once much loved, and much quoted in my own family, but out of fashion thanks to its huge cast and baggy structure. Nothing much happens, but within the story of a family celebrating a golden wedding anniversary for one generation and a younger generation suddenly achieving love, is a vast raft of emotional and social detail, all beautifully and subtly brought to life. Burns is a director who makes changes only in the service of the play and lets the words speak. They were spoken beautifully by a cast that included Lindsay Duncan and an exceptional Billy Howle.

2. Till the Stars Come Down, National Theatre

I’m conscious that this list is National Theatre heavy, but the conclusion of Rufus Norris’s time as artistic director has brought some gems that accord perfectly with my own taste. I’ve loved the writing of Beth Steel for ages, and this play about a wedding that collapses under the weight of terrible passions revealed and family tensions snapped is a glory. The writing’s precision, the way it catches the cut and thrust of women talking to each other, is rare. Bijan Sheibani’s vivid direction increased the sense of complicity, that these were people we might know, struggling with problems we might experience. Lorraine Ashbourne gave a devastatingly funny performance as the interfering – and increasingly sozzled – aunt. It can be seen on National Theatre at Home for those who missed it.

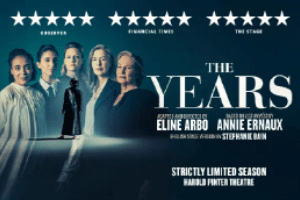

Another play about women. Or at least a single woman as a representative of us all. In this astonishing adaptation by Eline Arbo of Annie Ernaux’s memoir of her life from the end of the Second World War to the present day, five exceptional actresses – Garai (her second appearance on the list), Deborah Findlay, Anjli Mohindra, Gina McKee and Harmony Rose-Bremner – played the woman at different points in her life. They told the story of her childhood, of growing up in the 1960s, of a terrible abortion, of motherhood, of lovers and loss, of happiness and sorrow. The storytelling was fluid and fluent, as the women adopted the roles of different characters, of commentators and the protagonist. It was unbelievably moving and engrossing. In the audience, people – men and women – leaned forward in absolute empathy, recognising themselves and aspects of their own lives in the narrative unfolding. I saw it on a rainy matinee; its power changed the temperature of the day. It is an exceptional example of the communal power of theatre and its ability to encompass worlds in a tiny space. Thank goodness it is being revived at the Harold Pinter Theatre from January 24. It means I can see it again.