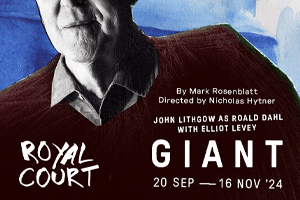

Giant review – John Lithgow is a powerful presence as a monstrous Roald Dahl

The show has its world premiere at the Royal Court

John Lithgow looks a bit like Roald Dahl. When he sits in a chair, his height means he has to fold up his long limbs like a paper clip; he is almost a giant. And his terrific performance is a compelling reason to see this play about Dahl – a giant of children’s literature, who was also a self-confessed antisemite.

Writer Mark Rosenblatt, previously best known as a director, takes as his starting point a review that Dahl wrote for a literary journal about a photojournalistic account of the 1982 Lebanon war. His denunciation of Israel and defence of the Palestinians is pockmarked by antisemitism.

As a result, Dahl’s fiancée ‘Liccy’ is hosting an emergency lunch at his home in Great Missenden, in the summer of 1983, at which his British publisher Tom Maschler and a representative of his American publisher (who are both Jewish) meet to try to prevent the fall-out damaging the publication of his new children’s book, The Witches.

The lunch and the American sales director Jessie Stone are both imagined. The article and Dahl’s subsequent more extreme statements of his position are not. They are his words. The tension of the play is that Rosenblatt introduces us to a man who is witty, charming and ferociously intelligent – and simultaneously a monster, a gleeful, malicious child determined to have his own way.

When we first meet him, Dahl is already in a furious mood. Liccy has embarked on a house renovation, elegantly conjured by Bob Crowley’s set which has a back wall covered in sheets of industrial plastic and colour samples pinned to the walls. He has back pain and he’s jealous of the amount of attention and money Quentin Blake is receiving for his book illustrations: “in flutters the Sidcup cherub and swoops off with half my royalties.”

Maschler, a wonderfully insouciant Elliot Levey, humours him with well-practised tolerance. He’d rather be playing tennis with Ian McEwan and doesn’t see why every Jew should have a view on Israel. But when Romola Garai’s Stone arrives, she pours oil rather than balm on the troubled waters, challenging Dahl’s “incendiary ideas”, arguing that “an entire race of people is being blamed for the actions of the Israeli army.”

The first act, directed with classy assurance by Nicholas Hytner (like Lithgow making a much-delayed Royal Court debut), does what good theatre can do better than any other setting, holding and exploring complex, contradictory views without oversimplification. The play was first conceived in 2018, but landing now, given the ongoing events in Lebanon, it has an almost overwhelming topicality.

And Rosenblatt is anxious to give Dahl motivation and reason for his arguments. His horror at the slaughter of Palestinian children rings out loud and true. The tragedies of his life that he approached and overcame with the same cussedness that he now brings to winning an argument are given full weight. His relationships with Liccy (played with loving anxiety by Rachael Stirling), his loyal gardener (Richard Hope) and a perky Australian housekeeper (Tessa Bonham Jones, doing a lot with not much) all reveal different shades of his character. Yet his confrontation with an outraged Stone – played with a winning mixture of nervousness and passion by Garai – is devastating and ultimately damning.

In the second act, as he becomes more intransigent and defiant and she vanishes from the scene, the tension diffuses. But Lithgow, long limbs flexing and restless, eyes wide and glinting, is never less than riveting, perfectly capturing Dahl’s petulance and his delight at scoring points, making his cruelty spring from the same source as his curiosity.

In the end, he is unforgivable, pushing even the tolerant Maschler away. But his publisher still speaks in his defence, and Levey gives the words great weight: “He deserves criticism for what he’s said, but in his books, he picks a glorious, playful path through the chaos of childhood. It’s the rarest of gifts. To show its cruelty but take you out the other side.”

It’s a play that doesn’t quite decide where it stands in that argument about whether you can loathe the man and admire the art – but thanks to Lithgow, it compels while it is making it.