Review: Pinter Five The Room / Victoria Station / Family Voices (Harold Pinter Theatre)

© Marc Brenner

Listen to the first words ever spoken in a play by Harold Pinter. A woman in her 60s, sets down a meal for her husband in a dingy, grey room. "Here you are," she says. "This'll keep the cold out. It's very cold out, I can tell you. It's murder."

If Jamie Lloyd's Pinter at the Pinter season proves one thing, it's that from the very beginning Pinter absolutely understood the weight and value of words, the way a casual phrase, in common use, can open up a chasm of possibility. In Patrick Marber's devastating production of The Room, written in 1957, Jane Horrocks as Rose drips the sentences in a wheedling insinuation, somewhere between a reassurance and a poem.

Rupert Graves' Bert looks on silently, something like contempt on his face, as she rattles on, hands constantly moving, eyes wary. She underlines her own happiness with the security of the room and her fear of unknown terrors lurking outside, in the basement, above her head. "This is a good room. You've got a chance in a place like this." When there's a loud rap on the door there is genuine fear, until Nicholas Woodeson's landlord barrels in, bearing a spanner, knocking on the pipes. He sits and talks of his life, moving from absurd reminiscence into profound sadness as he remembers a now-vanished sister. "I don't believe he had a sister, ever" says Rose as he leaves, another bit of unsettling undercutting of the kind that marks this shifting, scary play.

The value of this wonderful exercise in staging all Pinter's short plays is that each shines a light into the others, making their revelations more intense. In Pinter Five, The Room, often played as an exercise in pure fear, a precursor to The Birthday Party, takes its place alongside Victoria Station (1982), and Family Voices (1981), two plays that mine truths about love as well as terror.

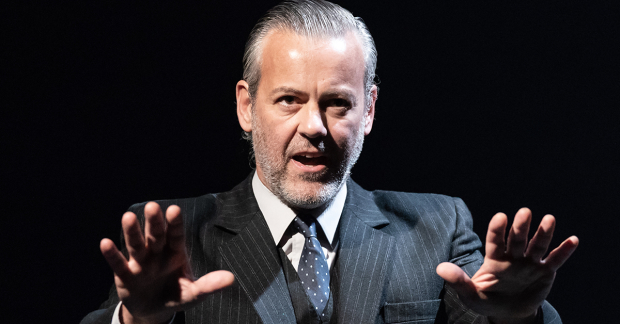

Victoria Station is a joy; a 10-minute comic exchange between a minicab controller (Colin McFarlane) who wants driver 274 (Graves) to pick up a passenger at the titular interchange. They talk framed in Richard Howell's soft light in two windows that open on Soutra Gilmour's versatile cube of a set, in a dialogue that has the quality of a dream or an existential nightmare. McFarlane makes perfect use of the pause as he charts the controller's rising exasperation; Graves superbly shades from blank incomprehension, to bewilderment to something ineffable that might be love, or loss, or complete despair.

It is Graves' night in the acting stakes. He's magnificent too in Family Voices, originally a radio play, now fluidly staged, a conversation by letters that never arrive between a father, a mother (Horrocks again) and a son (Luke Thallon, excellent) who has run away from home and finds himself in a boarding house full of eccentric characters who treat him as a pet. There's a void of sadness that opens up as they speak, a sense of aching absence under both the bright words of description or the bitter words of recrimination. "What I have to say to you will never be said."

Marber directs all three plays with absolute control, allowing space for the language to breathe while never losing his precise overall sense of the multiple layers within each piece. The performances, like the plays themselves, are both complex and simple and entirely compelling. You feel yourself leaning forward, wanting to catch each breath. What a great, illuminating season this is!