Review: I Wish I Was a Mountain (Brighton Festival)

Toby Thompson’s spoken word piece runs as part of the Brighton Festival

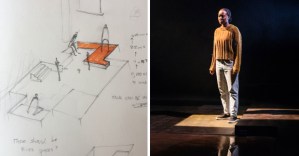

© Jack Offord

Performance poet Toby Thompson spent years working in a children's theatre, and got pretty sick of the glockenspiel. So when he came to make his first family show, a retelling of the Hermann Hesse fairytale Faldum, he decided to do things differently. I Wish I Was a Mountain features two record players on which Thompson spins jazz tunes by the likes of Bill Evans, Horace Silver and Nina Simone, and an upright piano on which he sometimes jams delicately along. "Have you ever seen a record before?" he asks the audience, before breaking out into an excitable explanation of the magic of vinyl.

Co-produced by Brighton Festival and Imaginate, this touring show doesn't draw on the most obvious of sources. It's a strange story in which a wandering wizard offers to grant everyone in the town of Faldum one wish, with outlandish and deeply philosophical consequences.

But then Thompson isn't your obvious teller. The young Bath-born wordsmith is a rather shy soul with the look of a children's book illustration: big-eared, wide-eyed and fluffy haired, with arms that flail about when he's animated and stick awkwardly to his sides when he stands still. He doesn't have the brio you might expect from a Glastonbury Poetry Slam Champion who Kate Tempest has declared to be 'the future'. If he had one wish, he tells us at one point, it would be for this show to go well, and to remember all the words.

And it does, and he does, albeit with a nerviness that sometimes blurs the dramatic pacing. It doesn't prevent him building in some playful audience interaction, though. There's a lovely moment when Thompson invites us to imagine the little Germanic town of Faldum by playing a game of I-Spy. "I spy with my little eye, something beginning with 'S'" he says, gazing upwards. "Ceiling!" shout three children in the front row. "No, Stars!" he laughs.

In Anisha Fields' simple design, the stage is dotted with little wooden houses, which fit together like nested boxes. Once they are unpacked, Thompson suggests a road by linking them with a sprinkled trail of sand. The quaint visuals contrast with contemporary flashes in Thompson's rhyming poetry. "This is where the story really gets fierce", he says, before relating how the town's violinist wishes for an instrument that makes a sound 1000 times more beautiful than birdsong. As he plays, he starts to dissolve, becoming one with the music. Like disapparation in Harry Potter, Thompson explains. Or, wait, see this glass of water? And he drops in a tablet and lets it fizz away to nothing.

I would have liked more such moments, of Thompson boldly gripping hold of what theatre can do that spoken word can't. But I valued his gentle, companionable approach to a story that exposes the human habit of wanting, and poses big questions about the boundaries and location of the self. And when the boy who wished to be a mountain tires of his lonely vigil and makes a second request, we get to hear Nina Simone's "How it Feels to be Free".