Review: Death of England (National Theatre)

© Helen Murray

Michael's dad is dead – keeling over onto his son after England's ignoble defeat to Croatia in the 2018 World Cup semis. Michael is left to navigate what's left behind – his fractious relationship with his family, the remains of his father's business, and his own seething sense of self-loathing.

So is the premise for Roy Williams and Clint Dyer's new one-man show, which arrives like a smouldering poker in the smaller Dorfman space at the National. It's an uncompromising work that never for a second shies away from some burning questions – tackling contemporary themes of racism, political disillusionment and the place of an individual within both a community and a fractured nation.

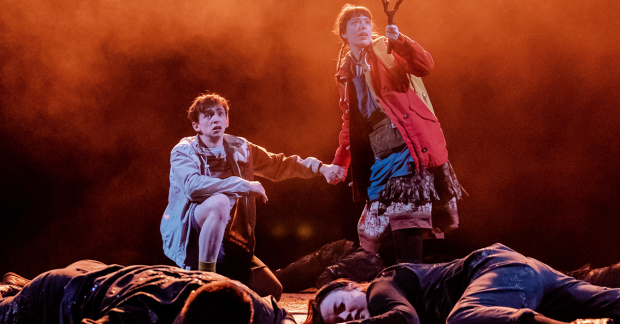

Actor Rafe Spall – muscular, jocular, sweaty – captures every essence of Michael's bubbling self-loathing. Cut him and he'd bleed torment. He comes unfiltered, blubbering, babbling and sometimes baffling the audience – hopping out into the theatre pit to offer out custard creams and pat punters on the back. He's the lad round next door revering his dad's Oasis LP – the guy flogging the flowers on the corner, afraid of leaving a protracted silence. Wild, untamed, but always up for a laugh.

As the 100-minute monologue progresses Michael's masculine impulses simmer, ready to boil over with the slightest bout of pressure. It's a solo tour-de-force of a performance from Spall (under the direction of Dyer): hurtling himself across the giant cross of designers Sadeysa Greenaway-Bailey and ULTZ's raised platform, plucking props from under nooks and crannies, necking pints and snorting coke in a toilet cubicle.

Williams and Dyer write strongly, allowing Spall to conjure up the different figures in Michael's life – his gnarly, antagonistic sister Carly, his best friend Delroy, Delroy's imperious mother, his own mother – each apathetic, writing him off as a failure. If anything it feels like the play doesn't push far enough – and one revelation, where a secret-harbouring stranger appears in Michael's life with a rattle of keys, is an opportunity squandered to delve deeper into both the psyche of a protagonist and, by proxy, a nation. Another coup-de-theatre is a fleeting, astounding moment that recedes quickly.

The one-note ferocity can wear itself out – a flame extinguishing itself after burning through all the oxygen in an enclosed space. Perhaps that's the point – that we, as an audience, get numbed to tormented rage the longer we witness it. But in the wake of a divisive referendum and a redrawing of political ley lines, more plays like Death of England need to exist on British stages. They need to be howled from venues across the nation.