Review: Betrayal (Harold Pinter Theatre)

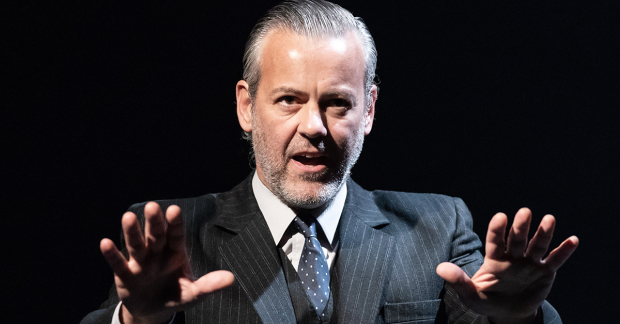

© Marc Brenner

The great revelations of Jamie Lloyd's Pinter at the Pinter season have sprung from the way the director has taken all the author's short works and made plays that have been rarely seen seem suddenly essential. In looking at them afresh, he has brought them to life.

The revelation of his concluding production of Betrayal – not quite a short play, but certainly a concise 90-minutes – is to take a play that has become very familiar and make it unfamiliar and strange. What can often seem like a naturalistic description of the corrosive effects of a seven-year secret on a marriage and a friendship, which is distinguished mainly because it begins at the end and unfolds backwards, suddenly seems a chillier, darker piece. Lloyd has scraped off all the surface accretions and with the help of a devastating performance from Tom Hiddleston, uncovers the raw passion and terror beneath.

The freshness of the approach is clear from the opening scene. As Emma (Zawe Ashton) and Jerry (Charlie Cox) sit on chairs, having drinks, discussing the affair they once had behind the back of her husband and his best friend Robert (Hiddleston), Hiddleston actually stands at the back of the stage, like a dark figure of accusation and betrayal.

From then on, the triangle of their tangled relations doesn't remain an abstract notion, it is a physical presence, a brooding shadow that affects even the simplest of gestures. The three actors stand on a revolve and literally circle one another, like gladiators before a fight, sometimes speaking and present, sometimes silent, but never absent.

For example, one of the leitmotifs that runs through the play is Jerry's memory of throwing Emma and Robert's daughter Charlotte in the air. Here we see the act – the child caught, laughing. Throughout the subsequent scene, where Emma and Jerry meet in their love nest, Robert circles the stage, his daughter asleep in his arms.

The effect is like being plunged into the inside of someone's mind – somewhere between nightmare and memory. It's emphasised by Soutra Gilmour's neutral set, its marbled walls conjuring trendy living rooms and the streets of Venice with a minimal and stylised effort. Jon Clark's lighting is similarly both realistic and symbolic, full of shadows and sudden shafts of sun.

Lloyd directs to emphasise the silences, the long pauses where the trio simply look at one another, their faces full of feeling, their hearts full of passion, anger, despair, and doubt. Cox rises brilliantly to the challenge of sitting absolutely still and speaking volumes while saying not a word. His Jerry is a weak, charming man who seethes with the need to be loved, his constant half smile and warm eyes begging for forgiveness, absolution, understanding.

But it is the casting of Hiddleston in the traditionally less showy part of Robert that is the revelation. Betrayal is famously based on Pinter's long affair with the broadcaster Joan Bakewell, but time – and Bakewell's own commentary – have altered our view of the character of Emma and Zawe Ashton – all restless gestures and constant unhappiness – struggles to give her much force. At this distance, Betrayal feels less like a portrait of the destructive power of love and more like a study of men at bay, baring their souls under the veneer of not caring.

In this context, the long central section where Robert discovers Emma's betrayal through the arrival of a letter acquires astonishing weight and Hiddleston charts each moment of discovery. In the early part of the play, he has been all clipped control, delivering even the shocking line about hitting Emma – "the old itch"- with cold contempt.

But here we see the moment of his disillusion, and his pain, hardening to anger, to a fake casualness that is astonishing to watch. His eyes fill with tears and the emotion is almost overwhelming. The subsequent scene where he encounters Jerry over lunch, and disguises his feelings with ferocious eating and drinking, is simultaneously comic and heart-rending, wonderfully observed. It is a performance full of easy charisma and intense truth.

It makes the play boldly bleak, an examination of the human condition as savage as any offered by Samuel Beckett, full of torrents of language that sound like poems, and spaces between things that suggest a void. It is Betrayal as I've never seen it before, and like this entire season, it bathes Pinter in a brilliant new light.