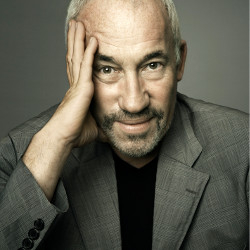

My First Play… Simon Callow

To celebrate the 25th anniversary of leading theatre publisher Nick Hern Books, we’re running a daily extract from its popular book ”My First Play” every day this week. Our final subject is veteran actor and playwright Simon Callow, whose solo shows include ”A Christmas Carol”, ”Being Shakespeare” and ”Inside Wagner’s Head”

© Kevin Davis

I was an almost total write-off at drama school in my first year. I scraped through at the end of the year more because of my obvious passion and desperation than because of any evidence of talent or indeed comprehension of the work.

Things scarcely improved during my second year, though at least I was less tired thanks to a grant that a kindly ILEA had given me. I was still struggling against a terrible internal block which refused to allow me any sort of free expression: everything I did was controlled to the last degree. I seemed hell-bent on impressing some invisible admirer. I probably seemed very self-satisfied, very confident, but I knew my work was rubbish – knew, not least, because my

teachers, with varying degrees of tact, told me so, over and over again.

‘Leave yourself alone!’ they chanted, almost in unison. It took two liberating experiences to unlock me from the prison in which I had incarcerated myself, to release the emotional life I had so firmly bottled up. The first shock was administered by the great acting teacher, Doreen Cannon, who goaded me – there is no other word – to combustion point during an Extreme Emotion exercise, through which I was sauntering with my customary nonchalance, impersonating, I think, George Sanders or some other unspeakably cool dude. Prodded by Doreen, I finally lost my temper and exploded all over the class. It was profoundly satisfying, the first time, I suspect, ever in my life till that point, that I had dared to give in to an emotion.

Only a few days later, in another class, I was acting in a piece that I had also written and directed, about fourth-century Greece. Preoccupied with my writerly and directorly responsibilities, I stopped seeing myself from outside, and simply played the character I had given myself, an Ancient Greek Everyman, whom I had roguishly called Testikles. For the first time, the thing I had so strained for over the last eighteen months – to make people laugh – came completely naturally. I was aware of an unaccustomed bodily relaxation, as if an iron cage – a suit of armour, as heavy as it was constricting – had been removed from me. Halfway through the course, I at last felt ready to begin training as an actor.

The first play I did after that was by Feydeau, Le Dindon, the play later wittily translated by Peter Hall and Nicki Frei as An Absolute Turkey, and I had been given the part of Major Pinchard, who, with his deaf wife, innocently visits the brothel where Act Two is located. It is a secondary part, but the new me fell on it hungrily. No longer out to impress with my control, charm and self-possession, I wanted to give myself over to the character. As always, Feydeau gives you the whole man in a few lines, his passions, his confusions, his contradictions. Pinchard, the military man, when plunged into a scene filled with amorous possibilities, becomes skittish and gallant, but then turns fiercely protective of his unhearing wife. I read everything I could about Feydeau, I studied the cartoons of Sem, the incomparable chronicler of bourgeois life in Belle Epoque Paris, I listened to operettas by Offenbach, Messager, Reynaldo Hahn.

I drew on the memories of pre-First World War Paris of my French grandmother and her sister. I found and repaired a uniform for the Major, I purloined my late grandfather’s hand stick for him, I made him a kepi from white cardboard and painted it, I grew a moustache and borrowed some moustache wax for it from an old actor friend, for a few shillings I bought a monocle from a bric-a-brac shop in the Vauxhall Bridge Road. I fell in love with Buffy Pinchard, as I called him, and would spend whole days as him, going into the local Chalk Farm shops and placing my order in his impossibly fruity voice.

Rehearsals were, for me, glorious. I felt I had nothing to prove, I simply had to give in to the Pinchard life force. In doing so, I found myself for the first time in my training able to listen to what the other characters were saying, and to be spontaneously astonished or delighted or dismayed by it. The mechanics of the scenes are so meticulously worked out by Feydeau that one simply has to follow his instructions to the letter. If one does, one becomes part of the massive energy he generates; one is swept along by the play’s manic imperatives. The laughter that Buffy and his deaf wife, wonderfully impersonated in that production by the statuesque Australian actress Sue Nicholson, was glorious, but it was a bonus. The important thing, the exciting thing, was Being Buffy. I was absolutely at his command.

I’m very much afraid that I’ve never given a better performance of anything subsequently. The joy of discovery, the freedom, the innocence have all been replaced by something more knowing, more self-conscious, more studiedly skilful. What Dickens called ‘the joys of assumption’ have never entirely, thank God, deserted me, though that first love affair with Buffy has proved, like all first loves, unreproduceable.

My First Play is published by Nick Hern Books. For a 25% discount and free UK p&p (total price £7.49), enter the code WOS FIRST at checkout when buying at nickhernbooks.co.uk/my-first-play