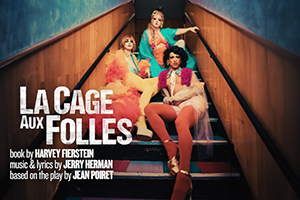

La Cage aux Folles at Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre review – sparkling, life-enhancing, yet timely and urgent

This is the sort of show that makes my job simultaneously a total pleasure and a bit of a challenge. It’s pleasurable because this is a well nigh perfect rendering of a superbly crafted musical (as well as a glorious coda to Tim Sheader’s tenure as artistic director of Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre), and challenging because…well, how many superlatives can one use without sounding like a broken record?!

Although La Cage aux Folles was a massive Broadway hit, it wasn’t embraced by London at first: the glossy 1986 Palladium premiere lasted a mere seven months, having been unfairly conflated by the gutter press with the ongoing AIDS crisis of the time, particularly ironic for a show that vehemently espouses family values, albeit while showering them in “sparkle dust, bugle beads, marabou, ostrich plumes, Shalimar” to quote one of Jerry Herman’s transporting ear-worm numbers. It wasn’t until the smaller scale, rougher-round-the-edges Menier Chocolate Factory version more than two decades later, which enjoyed a long-running West End transfer, that Herman and Harvey Fierstein’s big-hearted tuner, based on a French farce that also inspired the mid-1990s Hollywood movie The Birdcage, got the love over here that it deserved.

Sheader’s 1970s-set staging lands somewhere between those earlier iterations in terms of aesthetic and budget. Although production values are high (Ryan Dawson Laight’s frequently outrageous costumes and Howard Hudson’s twinkle-some lighting are gorgeous but garish), the titular St Tropez nightclub run by middle-aged gay lovebirds Georges and headlining drag queen Albin has more than a whiff of Blackpool, or indeed any rundown British seaside resort where high camp is the predominant style choice.

There’s definitely some grit in this pearl: Colin Richmond’s set is glitzy and evocative but look closely and you’ll notice mould and peeling on the walls, and weeds peeping through the cracks. Meanwhile, the glamazon chorus line of drag Cagelles who fearlessly tap, sass, glide and bash their way through Stephen Mear’s dazzling choreography (surely there’s no better creator of traditional showbiz dances at work in British theatre right now) are a joyfully diverse bunch who also get to lug scenery around and watch from the sidelines like a glittery Greek chorus.

Despite the French setting, the actors use a variety of decidedly non-continental accents. Thus Billy Carter’s suave Georges is Northern Irish, Carl Mullaney’s lovable Albin is broad Northern, their gender-fluid maid Jacob (Shakeel Kimotho, stunning) changes dialect by the line, Debbie Kurup’s commanding, deliciously OTT restauranteur is straight (if you’ll pardon the expression) out of Tyneside, and Danielle Coombe’s blousy, leopard-skin clad café owner is pure Essex. Then the Cagelles include JP McCue’s Scots pocket rocket, Jordan Lee Davies as a woozy Welsh coloratura and Jak Allen-Anderson’s terrifying, whip-wielding, vaguely Teutonic supernova. It could have been distracting, but it mostly makes the characters all the more relatable and humorous.

The timeless Jerry Herman score – brassy yet lyrical – is a beauty. It’s a romantic, memorable parade of songs awash with sentiment and theatrical excitement, climaxing with that stirring paean to self-acceptance “I Am What I Am”, delivered here with blistering power and no small amount of fury by Mullaney as a heartbroken Albin facing usurpation from the unconventional family he’s held together for decades. This is in order to project a “wholesome” image for the benefit of the bigoted politician whose daughter is set to marry Jean-Michel, the son Georges helped conceive twenty-four years previously.

The only thing more moving than Mullaney’s thrilling performance of the most famous number (except maybe for the title song from Hello Dolly!) in the Herman catalogue, is the anguish of Carter’s Georges when he realises quite what he’s asked his partner to do. It’s a terrific, troubling act one closer.

Elsewhere, the acting tends to be bouncy and flamboyant – Chekhov this ain’t – but rooted in just enough truth that when Fierstein’s script turns heartfelt, it’s genuinely affecting. His writing has a baroque preciousness at times but also a keen wit. You can’t help but care about these people, even Jean-Michel, whom Ben Culleton invests with just enough youthful charm to mitigate against his appalling insensitivity, and his uptight mother-in-law, played with understated but delightful comic flair by Julie Jupp, costumed like a brunette Margaret Thatcher until she lets rip in the riotous finale.

Her ghastly husband was played at the performance I saw by Craig Armstrong (understudying John Owen-Jones) who effected an astonishing transformation from his act one track as a can-can-ing Cagelle to this ramrod straight, pompous right winger: remarkable work. Kurup, a bona fide leading lady under normal circumstances, might be criminally underused but spins comic gold out of a tiny role.

Carter and Mullaney are an entrancing central couple. In an exquisitely realised, fully rounded portrayal, Carter makes vivid the contrast between Georges’s dashing onstage persona as compère and host of the nightclub, and his real-life role as Albin’s flawed life partner. Mullaney suggests a hard-won core of steel (this is the 1970s after all) beneath Albin’s flouncing and histrionics, and has the comic instincts and sad-eyed pathos of a true clown. I suspect this is a performance that will become richer and deeper as the run progresses. Jennifer Whyte and Ben Van Tienen’s band sound just grand playing Jason Carr’s vital, full-bodied orchestrations, and the Cagelles collectively exert a fascinating power even as they’re a heck of a lot of fun. Overall, this is the kind of evening where it’s impossible to wipe the soppy grin from off your face.

It’s amazing to think that the same amount of time (40 years) has elapsed between this revival and La Cage’s New York premiere, as there was between that original production and the 1943 debut of Oklahoma!, the show credited with reshaping the American musical. La Cage’s central message of being true to oneself and love being the guiding force to an authentic life, has never felt more timely or urgent though, and placing two men at the romantic centre of a splashy musical comedy may seem less edgy now than it did in 1983, but was equally as groundbreaking as that Rodgers and Hammerstein masterpiece.

One of the show’s most life-enhancing anthems repeatedly proffers that “the best of times is now”; at present, that’s hardly true of the world at large, but for two and a half sparkling hours, this colourful warm hug of a musical will convince you otherwise. More than any other Regent’s Park show I’ve seen, this looks ready to transfer to a conventional theatre as soon as this summer run is over, but just in case it doesn’t, I’d urge you to grab tickets before it inevitably sells out. This is a treat.