Dr Semmelweis review – Mark Rylance is mesmerising in West End tale of medical misfortune

The 19th century historical tale is brought into tragic clarity

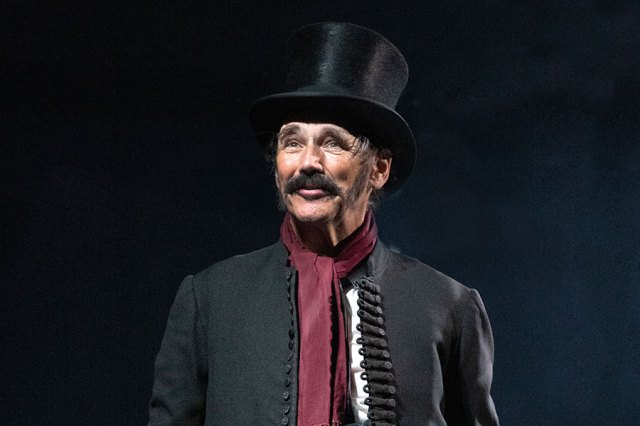

There is nothing like seeing Mark Rylance centre stage. He seems to live there. However good he is on film or on television, it is in the theatre that you see most clearly what a vital actor he is, how he makes characters breathe, apparently by the simple act of being.

In Dr Semmelweis he has the perfect setting for his gifts. It was Rylance himself who provided the idea on which Stephen Brown’s play is based. As presented here, Ignaz Semmelweis is a historical figure of tragic proportions. In 1847, some 20 years before Louis Pasteur made his bacteriological breakthroughs, Semmelweis discovered that “childbed fever” which was killing large numbers of mothers and babies at the Vienna General Hospital, could be drastically reduced by getting doctors to wash their hands in disinfected water.

But resistance from the medical establishment stopped his discovery being acclaimed and implemented and Semmelweis ended his life in a mental asylum dying – ironically enough – from sepsis, probably caused by an untreated wound after he had been beaten by guards.

His story is utterly riveting, but what gives it such ferocious force in the theatre is the way that director Tom Morris stages it as a kind of fever dream, with time frames slipping into one another and the action literally circling around Rylance’s frantic, and increasingly isolated central figure.

Ti Green’s set, which looks like a panopticon prison design, adds to the effect: its walls are black as pitch, and there’s an oculus above, letting through shafts of light designed by Richard Howell. Below is a revolve. This space is populated not just by the doctors and by Pauline McLynn’s resourceful nurse, but by the ghosts of the mothers who have died, peering eerily over the balcony, never absent from the staging just as they are never absent from Semmelweis’s mind.

In corsets and gauze skirts, they are embodied by dancers and the Salomé string quartet, playing Adrian Sutton’s score which interrupts the story with its sharp discords. Antonia Franceschi’s choreography lets the women flit through the dialogue, sometimes gently, sometimes in great rushes of movement, piteous reminders of the lives being sacrificed. “Knowledge masked in ignorance is murder,” says Semmelweis.

Their presence and the vigour they bring gives an energy to the entire play which often requires a concentration on the workings of the mind, as Semmelweis pieces together the clues that lead him to understand that by not washing their hands doctors are killing the people they exist to save.

The ebb and flow of discovery – with mimed autopsies and one extraordinary ballet sequence to Schubert’s Death and the Maiden where Semmelweis physically enacts his desire to save the innocent from death – is made exciting. The story never loses its grip, nor its meaning. The good doctor’s undoing comes from the same source as his discovery: his reluctance to play the game, to conform to accepted ways of thinking, makes him an outsider in the medical establishment he must convince. His arrogance and pride, his sense of exclusion because he is a Hungarian in an Austrian world, mean that he drives people away who might have supported him.

Rylance charts all this with incredibly upsetting precision; touchy, thin-skinned, he makes Semmelweis hard to like. But he also lets you see inside his head, showing the thrill of being part of a new way of thinking, indicating the panic as he half realises his mind is becoming disturbed. It’s an extraordinarily subtle and emotional performance.

It is surrounded by strong support especially from Ewan Black, Felix Hayes and Jude Owusu as the colleagues who try to support him. Alan Williams is suitably monstrous as Johann Klein, the professor who opposed his reforms. Amanda Wilkins makes a tender figure as Semmelweis’s loyal wife, but she gets saddled with too many explanatory metaphors and too many speeches which undermine the power of the narrative.

The play has already brilliantly shown us what has happened; we don’t need to be told it as well.