Catherine Love: Royal Court offers food for thought

What might theatre be able to tell us about what and how we eat?

The Royal Court, which since Vicky Featherstone‘s arrival has been prodding at a series of issues through its ‘Big Idea’ strand, has now settled on one of modern society’s biggest obsessions: food.

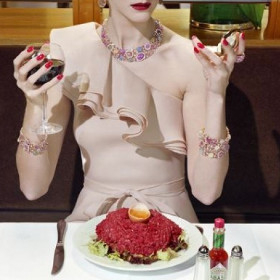

Whether worrying about where it’s from, how it’s cooked or how much of it we’re eating, food and the rituals that surround it consume a disproportionate amount of our mental energy. It’s this anxiety that Gastronauts, described as a theatrical dining experience, attempts to explore.

Details about the show are deliberately scant, with the Royal Court’s website revealing only that diners will be able to “make an informed decision” about what they do and don’t eat throughout the performance. Fussy eaters, one guesses, might be in trouble. The show was born in response to the horsemeat scandal and the renewed interest in food production that followed, so it seems likely that theatregoers will be asked to reconsider the food offered to them and where it might have come from, reconfiguring audiences’ complex relationship with what they eat.

As well as exposing the journey our food makes before reaching our plates, there is another side to eating that theatre might be even better placed to examine. What we eat is under constant scrutiny, but how we eat it is perhaps just as important. Meal times can act as a form of ceremony, bringing people together in a way that few other activities still do. Eating, like theatre, is a kind of ritual, one that is capable of creating and sustaining community. And in many cases it is a ritual that is coming under strain.

This community aspect of the dinner table was the focus of Only Wolves and Lions, a touring show that I took part in during this year’s Edinburgh Fringe. This intimate performance asks each of its audience members to bring along a raw ingredient, which are then used to collectively cook a feast. The choice of what to cook, the cooking itself and the eating of the meal are all collaborative activities, demanding audience members to work together in a way that few theatrical events, however supposedly “interactive”, manage to achieve. As well as feeding me the best meal I had in Edinburgh, the piece powerfully demonstrated the social value of eating together and left me reflecting on the possibilities of such rituals for forging communities.

And it is not just this and Gastronauts that are turning their attention to the act of eating. Bristol Old Vic recently presented The Table of Delights, a mash-up of restaurant and theatre experience that asked its audience to consider every aspect of food, while the Albany has just dedicated a whole festival to the subject. If the forces that control the food industry are increasingly detaching us from the processes of food production and consumption, then theatre seems to be attempting to slowly rebuild that connection.

While newspaper reports and documentaries will rightly continue to investigate what we eat and where it comes from, it strikes me that theatre – by framing a familiar activity in a way that makes us appreciate its performative and community forming qualities – might be particularly well placed to explore how we actually eat it. By framing one kind of ritual within another, perhaps shows like Gastronauts can make us question not only where our food comes from, but what role the communities it creates might play in our society.