A Tupperware of Ashes at the National Theatre – review

Meera Syal stars in the world premiere of Tanika Gupta’s new play, running until 16 November

Where most Alzheimer’s narratives are hopelessly bleak, Tanika Gupta manages to include not just the plainly heartbreaking in new drama A Tupperware of Ashes, but the profuse life already lived, as well as the many lives left to go on without protagonist Queenie. Her end is incredibly sad, but it is not her sum total, not even close.

Queenie is a strong-willed, Michelin-starred matriarch who, along with her late husband Ameet, made the risky trip to London from India as newlyweds to carve out a better life for their future children. Decades later, now a widowed mother of three adults, she has lost none of the fire that led to her great success. But her mind is betraying her, showing signs of Alzheimer’s at a flagrantly rapid rate. Now her family must contend with the ever-growing helplessness of a woman they have feared and respected all their lives.

This isn’t the first story we’ve seen trying to pick apart the impossible tragedy of the accomplished and formidable losing themselves to Alzheimer’s: Florian Zeller’s 2015 offering The Father showed the psychological descent as a nightmare; no-one is who you thought they were, nothing is as you left it, everyone is telling you what’s best, but you don’t recognise their good intent. The 2014 film Still Alice showed a woman in her seemingly physical and intellectual prime swiftly losing her identity. And more recently, Matthew Seager’s 2023 play In Other Words showed the heartbreaking collapse of a loving marriage caused by Alzheimer’s.

But where Gupta’s A Tupperware For Ashes diverges from this canon is the deteriorating mind’s invocation of the seemingly impossible: Queenie’s newfound ability to summon her late husband, for example, who she has had to live without for two decades. A poisoned chalice, no doubt, but a chalice nonetheless, Gupta allows for the possibility that Ameet has come to guide Queenie through this last chapter and accompany her to the next life. This idea isn’t didactic, it’s merely proffered, and even if you see it as a silly explanation for a serious tragedy, at least she has this one small consolation: that while she is suffering terribly, she does not always feel she is suffering alone.

A strong character such as Queenie is, of course, not without faults; as well as her children’s negotiating their reassignment as carers, they must also find a way to make peace with a difficult mother who can no longer apologise for, or defend, her past choices. Gupta especially excels at writing this dynamic, muddying the waters between Queenie’s own vitriol and disappointment towards her children, and the possibility that this is yet another symptom. Regardless, the words of your mother hurt just the same.

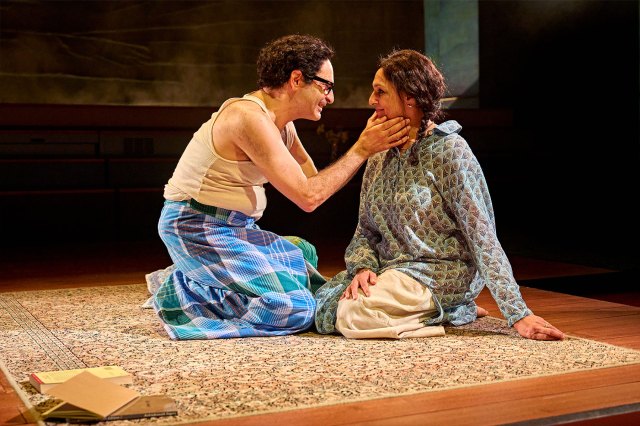

Meera Syal as Queenie is especially potent, her charm and dynamism morphing into belligerence and revilement and, later, into confusion and fear. The rest of the cast is uniformly excellent, and Stephen Fewell’s performance, playing various bit characters, preaches proudly the maxim that there is no such thing as a small part.

Director Pooja Ghai has truly brought in the A-team across the crew too. Nitin Sawhney has been drafted in to write the musical score, to powerful effect, leading us from the sweet nostalgia of early married life into the sharp miserable focus of Queenie staring into space as her children desperately try to bring her back to reality.

Rosa Maggiora’s set design, paired with Matt Haskins’ lighting seems, at first, almost too simple: a crepe paper backdrop changes colour depending on the timeline, and a few steps help to create more interesting levels. A couple of stools and a table, and that’s all we’re given. There’s no real drama to speak of. But paired with illusions designer John Bulleid’s precise and artfully sparing tricks of the eye, the mundane comes alive with the seeming magic caused by mental degeneration: a dressing gown disappears in the blink of an eye to be replaced by a party dress, a man climbs inside a suitcase as though it were a rabbit hole, only for the suitcase to be picked up and taken away moments later.

We see Queenie’s deterioration as a newly enrichened interior world, a spectacle for her eyes only, that is, before we look around at the rest of the cast and register their serious concern as a giant butterfly in the palm of her hand becomes a soiled tissue.