Review: Shebeen (Theatre Royal Stratford East)

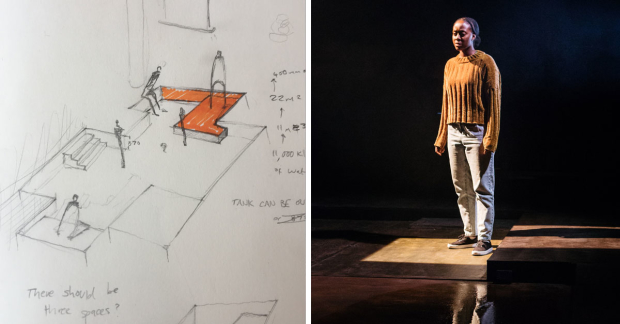

© Richard Hubert Smith/Nottingham Playhouse

The wallpaper's peeling, the kitchen sink's just a bowl. But sat in the sitting room of Pearl and George's terraced Nottingham home, there's a state of the art record-player, ready to roll. It's a giveaway. It's 1958, and they're just off the boat from Jamaica, stomachs still reeling to recall the waves. They're poor, but this couple know how to party.

A shebeen is an unlicensed bar on private premises. Mufaro Makubika's new vintage play – its style suits its setting – takes us inside. If it's not much by day, at night the place comes alive. Reggae beats bounce off the walls, rum tots are on tap and a steady flow of goat curry comes out of the kitchen. Martina Laird's Pearl presides with huge pride: the perfect host to a community craving a flavour of home. Her husband (Karl Collins), a former boxer, stands by her side with a show of togetherness; a performance of love.

Shebeen's politics sit just off to one side. Policemen knock on the door, ready to shut things down at the slightest sign of illegality, but where else can these men and women go? Black men are beaten by white mobs in the streets. Signs in pub windows warn them away, and even those that don't only cater to old English tastes. The shebeen's a safe space, a place to dance free. It's some corner of a terraced street that is forever Jamaica. But it needs men on the door, noise levels kept in check, troublemakers turfing out. Every so often, a brick flies through the front window.

It couldn't be more timely, with Windrush so in the news, and Shebeen lays out a good spread of immigrant stories. Theo Solomon's Linford charms his white girlfriend Mary in safety, as her eyes open up to a whole other world. Rolan Bell's spivvy Earnest puts on a sharp suit, but still faces overt sneers outside the shebeen. Aggression bubbles beneath the surface – frustrated factory workers overdo the drink and trussed-up young men pull knives on their peers. However spirited the party, Makubika sets up an expectation that something's going to go off. His play escalates quickly, and ends abruptly.

At its heart, though, is Pearl and George's relationship, and it's so tender and loving, so heartfelt and homespun, that it's enough on its own. Laird is phenomenal: warm, optimistic and welcoming. For all her dreams of building a business of her own, Pearl's Place, it's startling how quickly her hopes puncture and her hospitality deflates. Collins, meanwhile, reaches for the dreams he gave up, staring forlornly at a poster of his boxing days that hangs on the walls.

It's typical of the care in Makubika's writing, which resists the pressures of plot to stay true to the shebeen as a space. Matthew Xia's staging occasionally overcooks that – the acting's uneven – but Grace Smart's design wittily taps into its spirit with a silver show curtain that turns this terraced house into a dance hall. In that, Shebeen shows the start of a national transformation.