Review: Orca (Southwark Playhouse)

Every year, Papatango goes panning for gold. Its playwriting prize, now eight years old, tends to unearth distinctive scripts. From Dawn King’s rural dystopia Foxfinder to James Rushbrooke‘s small-scale sci-fi Tomcat, winners often instil a strong sense of reality into a far-off or fantastical world. Matt Grinter‘s Orca follows suit.

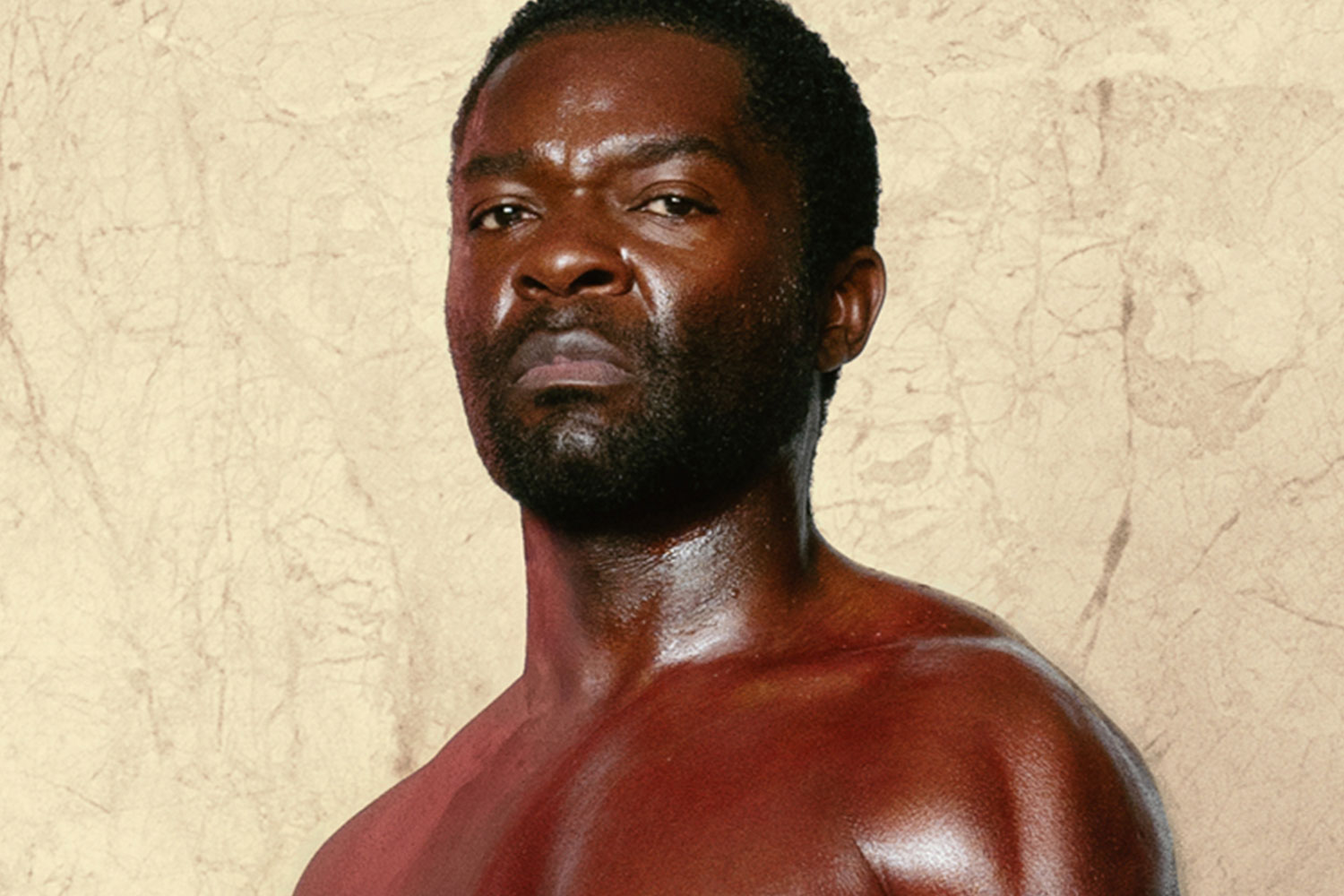

Set on a remote weather-whipped island, sustained by its fishermen and largely cut off from the mainland, Orca centres on a longstanding ritual. With orca pods preying on the nearby fish stocks, the community enacts a mock sacrifice every year in accordance with a local lore. Myth has it that a young girl was lost to the orcas long ago and, each year, one of the isle’s teenage girls stands in for her.

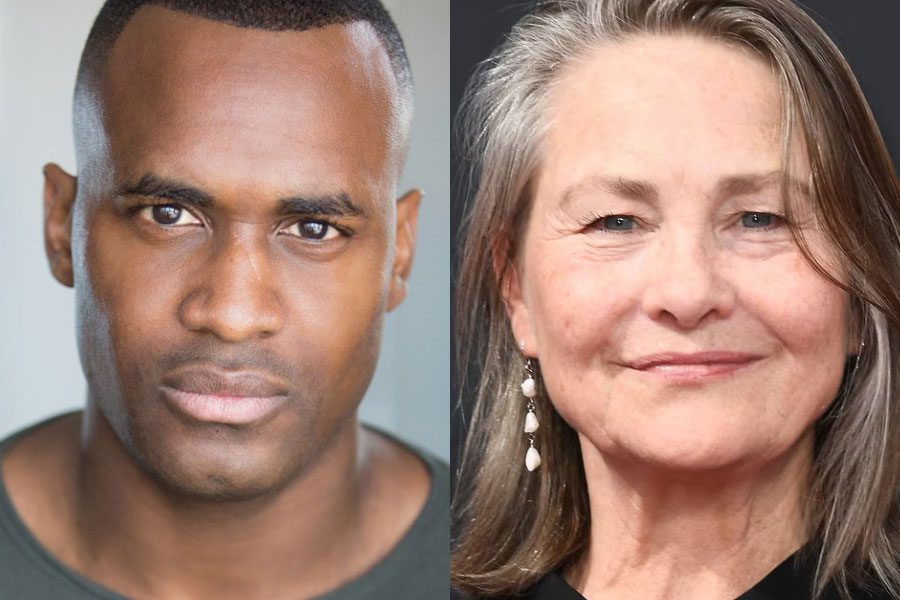

Grinter approaches the ritual through two sisters. Maggie (Rona Morison) tries to protect her dreamy, younger sister Fan (Carla Langley) from the fate that befell her, but their ostracised father sees her selection as a route back to the community’s centre. He carefully sews decorations onto her dress and speaks soothingly of the ritual, but Simon Gregor’s Joshua disregards the clear trauma and terror of last year’s Daughter Gretchen, who has just washed ashore semi-conscious and uncommunicative.

Though the riddle of the ritual unfurls too easily – the moment Aden Gillett’s ritual leader comes to collect his daughter with a glare at Maggie – Grinter writes with a real chill in the air. Orca has the eeriness of Jez Butterworth‘s remote rural thrillers, with a salt sea wind that cuts to the bone. Alice Hamilton’s production taps into its skewed oddity; the strangeness of a remote community that speaks in soft Scottish burrs and wraps woollen jumpers tight for comfort. Beneath the text, there’s the heaviness of unspoken, seemingly unspeakable, truths.

Much of that atmosphere comes from Frankie Bradshaw’s set: a creaky wooden pier, covered in barnacles and sea slime, splintered by the sea over decade. It’s an eloquent expression of social erosion; a community gone rotten with neglect. The island turns a blind eye to the abuse of power by its patriarchal leaders, and Grinter’s sharp on the way stories can cement toxic values in the name of conservatism and tradition.

In a sense, Orca is the exact inverse of The Crucible. Rather than young women inventing shrill accusations, Grinter’s abused girls go unheard. Their protests are quashed before their even voiced. Gillett’s imposing authority figure has the stature to silence anyone with a look, so hides in plain sight, but far worse is the obsequiousness with which Fan’s father gives his daughter up. Gregor can fawn one moment, then erupt the next – a mark of the way patriarch power trickles down.

Morison is gutsy as the daughter daring to stand up against it: upwardly defiant, but tender in the way she watches over both her sister, Langley’s dotty Fan, and Ellie Turner’s meek Gretchen. Grinter’s not the only promising talent on show here.

Orca runs at Southwark Playhouse until 26 November.