Review: Greek (Arcola Theatre)

© Lidia Crisafulli

"Where will I find another like him?" laments Mum on Dad's demise. "Whose vomit will I clean from the pillow?" Yes, we're in Steven Berkoff territory, but with a difference.

Theatre's roaring boy wrote his subversive take on the Oedipus story early in his career, soon after his calling card play, East. And Greek is very much East 2: four characters in a murky Tottenham-ised version of Thebes who pack their conversation with bile and other body fluids, ever ready to dole out a kicking to the marginals of society.

The miracle is how much of Sophocles survives. As the sun beats down on a plague-infested city – "The heatwaves turn it all to slime / And filthy germs hang thickly in the air" – the rats are on the march, but who's to blame?

Step forward Eddy (probable surname: Pus), our tale's doomed hero.

It's 30 years since Mark-Anthony Turnage fashioned this unlikely material into an opera, with Berkoff's playscript snipped to libretto-length by the composer himself in tandem with his director, Jonathan Moore. It sealed the young composer's reputation and set him on the road to Anna Nicole and other glories.

Now, buoyed no doubt by last year's successful revival from Scottish Opera, Moore has restaged Greek in the cloistered intimacy of the Arcola. Through some wizardry he and designer Baśka Wesołowska contrive to fit a freewheeling production and an 18-piece orchestra into the confines of Studio 1, and to do so effortlessly. The environment is a mixture of crude graffiti and polished dance floor, all splendidly lit by Matt Leventhall, and it oozes class.

Turnage's Greek is that rare thing in opera: a dizzy broth of bruising language and scalding imagery. Yet it barely skims the surface of the original's gleefully obscene text and avoids some of its more disturbing elements, perhaps aware that the score needs to communicate musically without undue distraction. And what a thrill-ride it is, with stamps and whistles, sideways nods and cheeky allusions ("The Laughing Policeman" gets a look-in during a particularly nasty riot). The composer reserves his lyrical music for the most coruscating lines, hence "Hang the c*nts and hang 'em slow" could almost slot into Sondheim's Sweeney Todd. There are no violins but the Hantanti Ensemble's solo viola, Anna Growns, squeezes out some dangerous harmonics above the stave, with Aileen Henry's harp a soothing antidote to the frenzy.

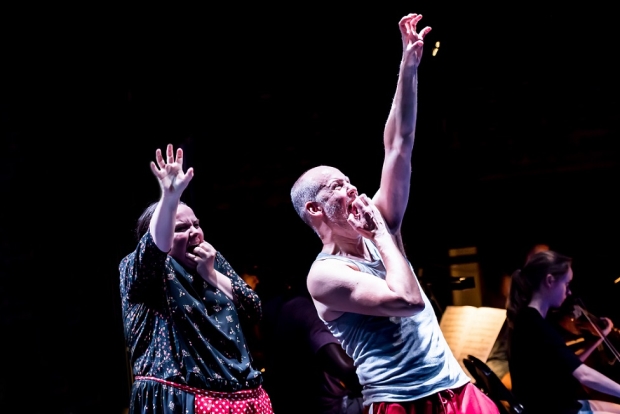

Tim Anderson conducts superbly and the production's overall intimacy sears the eyeballs – a feeling poor Eddy comes to know only too well. Moore's mastery of Berkoff's visual language makes for an authentic physical experience built on aggressive muscularity and balletic precision, with the tropes of silent comedy never far from the surface. No one projects these skills better than Philippa Boyle, a soprano who can gurn on a sixpence and lurch from clown to victim. She and the equally striking Laura Woods combine to embody the treacherous Sphinx who toys with baritone Edmund Danon's hapless Eddy.

Danon channels Mark Strong in this central role, aggressive, head-shaven and vulnerable, and he tears himself apart during the opera's closing scene. With Richard Morrison equally fine in the dual roles of Eddy's real and adoptive dads, it's a total Berkoff experience as well as a musical feast.

There is a school of thought that says the shock-jock playwright's day has passed. We are beyond chortling at naughty words, and as for violent mime we've seen it all before. So Turnage, if nothing else, has created a legacy beyond anything he intended when he adapted Greek in 1988: he's extended the play's shelf life.