Review: John (Dorfman, National Theatre)

The evening begins with a woman drawing back the heavy red velvet curtains, as if inviting us into her home. There it is before us. Dolls, models, miniatures cluttering every surface; Abraham Lincoln jostling for space with Santa Claus in the weeks after Thanksgiving. A Christmas tree gleaming in a corner, and lights twinkling up the steep stairs to the bedroom. To one side, there is a room called Paris, with breakfast tables neatly laid.

Chloe Lamford‘s design makes the guest house setting seem real. But like everything else about Annie Baker‘s brave, magnificent play, it has a flourish that also emphasises its theatricality. We appear to be watching a drama about the disintegration of a relationship – but we may in fact be witnessing something else entirely, or perhaps something else as well.

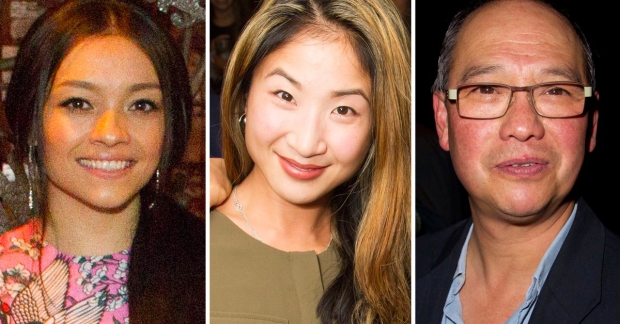

The bare bones of the plot are that ill-matched but appealing couple Jenny (Anneika Rose) and Elias (Tom Mothersdale) are visiting Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, site of the most famous battle of the American Civil War. They are staying in a cluttered bed and breakfast run by the eccentric Mertis (American actress Marylouise Burke), who has rooms called after Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, and Joshua Chamberlain. As they quarrel, Jenny spends more time with Mertis and her blind friend Genevieve (June Watson), bonding over a bottle of wine, talking about love. The lovers argue again; the women talk.

On the surface nothing much happens and it takes a very long time not to. The play runs to three hours and twenty minutes, with two intervals, one of which is partially taken up with a front of curtain speech by Genevieve, who has begun the second act with the words "That was around the time I went crazy" and now explains the seven stages of her madness, uncovering one of the themes of the play. "Imagine that," she says, gravely. "Sitting in the centre of your own life with no thoughts at all about what other people are thinking."

Yet, as in The Flick, staged at the National in 2016, Baker takes us by the hand and demands we gaze patiently at the unfolding action, watching the empty room when the participants are engaged elsewhere. Behind the intense naturalism, the long silences, the way conversations unravel slowly as in life, there is audacious artistry and careful craft. Mertis moves about the stage, moving time forward, setting the lights. Scenes of tension – when Elias finally loses his rag and threatens Jenny with the thing she most dreads – are balanced with moments of fierce humour as when they discover Genevieve sitting in the dark.

In the same way, Baker’s dialogue seems to be simple but her words drop like stones in a pond, the ripples reverberating. They are both psychologically revealing – as when Mertis tells a story about a doctor who "could have been kinder" to her – and poetic, as when she recites all the words that can be used to describe groups of birds – "an exaltation of larks" – rolling them around her mouth like an incantation. At one moment she simply reads a long passage from H P Lovecraft’s The Call of Cthulhu.

The phrase "what happened there?" runs through the play like a binding thread. The truth is we never quite know; there is something slippery about truth in John. We don’t ever really know what we are watching. This is a play stalked by ghosts, by hauntings, including those of the Gettysburg wounded whose amputated limbs, piled 10 feet high, once blocked the view from the windows. It is a place where a mechanical piano can begin to play on its own, where Mertis’ sick husband George may or may not exist, where dolls have feelings and objects have lives. Genevieve has been controlled by the thoughts of her husband, manipulated like a doll; Jenny pretends to be a statue so that Elias can move her like a mannequin. It is eerie and unsettling, strange within its ordinariness.

It is also a play about the numinous. Mertis, with her other-wordly oddity, asks her guests whether they have ever felt watched by a power outside themselves and both have. Jenny feels she has been embraced by the universe, Elias bursts into tears when he remembers his sense of being protected by a force that might be God.

Like other great American dramatists such as Edward Albee and Eugene O’Neill before her, Baker makes the domestic universal, asking existential questions about the nature of being within a confined setting. Yet her voice and methods are entirely original. Like Elias, she tells a good spooky story and weaves a spell that is entirely her own.

Such precise writing requires the most subtle and sensitive playing and it gets it here. James Macdonald‘s direction is nuanced and careful and all four actors are simply magnificent. Rose and Mothersdale perfectly capture the love-torn couple in all their shifting unease. As the blind seer Genevieve, Watson rings more meaning from the single word "Cold" than anyone could reasonably expect. And Burke is just perfect as Mertis, shuffling quietly around, stage managing events, managing to convey the sense of infinite wisdom and constant confusion in a single sentence.

Sometimes five stars doesn’t seem quite enough to capture the wonder of sitting in a theatre and being entirely engrossed in a story, completely entranced by a work. John is rich and magical, something special.

John runs at the National Theatre until 3 March.