Miss Saigon (Prince Edward Theatre)

I had not seen or heard Miss Saigon since the tumultuous opening night at Drury Lane, and while Laurence Connor‘s competent revival presses most of the right buttons in this melodramatic re-write of Madame Butterfly during and after the evacuation from Saigon in 1975, it’s neither as good as, nor better than, Nicholas Hytner‘s 1989 operatic original.

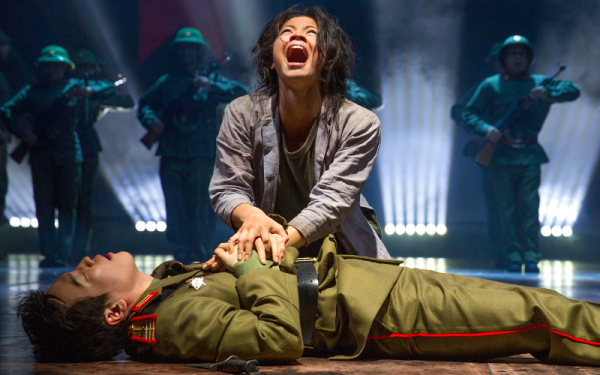

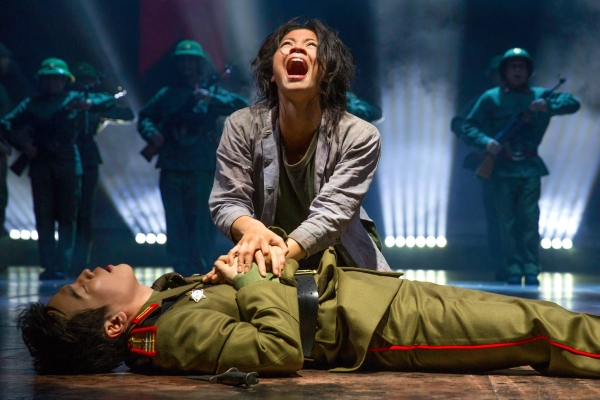

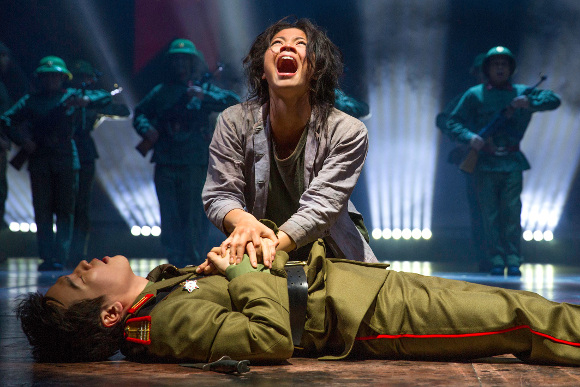

In one area, though, it is its equal: in the casting of 18 year-old Eva Noblezada – an American of Filipino and Mexican extraction – as Kim, whose astonishing voice is flawless in a wide register and whose acting is assured and touching, as she fights for her young son to have a new life in America.

The other flashpoint, the helicopter in the Saigon embassy scramble: how do they do it? Well, there is a partially real helicopter, but the rest is done by sound, lights and a bit of film. With Bruno Poet‘s lighting cutting up the stage in harsh cluster beams, the shack-like interior scenes in Saigon and Bangkok are shadowy and makeshift-looking, though the stage bursts into life for the nightclub razzle dazzle.

There’s no real attempt to break the mould (and Bob Avian has returned to supervise his original choreography), though Matt Kinley‘s design does score one notable trick of displacing a huge golden mask of Ho Chi Minh at the re-naming of the city (it was a giant statue before) with a similarly well-made Statue of Liberty mask in the Engineer’s climactic "American Dream" number.

The ideological oscillation between East and West is a feature of Claude-Michel Schönberg’s score, and the Engineer is the pimp who oils the wheels; instead of Jonathan Pryce‘s knock-out slimy nastiness in the role, we have a more slithery (and much shorter) Eurasian operator in the shape of Jon Jon Briones, who was in the chorus originally.

Kim’s Puccinian Pinkerton is the American GI Chris, muscularly sung but woodenly acted by Alistair Brammer; the show first takes off when Kim duets with his wife back home, Tamsin Carroll‘s full-voiced Ellen, in "I Still Believe," one of the few numbers by Schönberg and Alain Boublil that rivals the score of the same writers’ Les Mis.

Ellen, too, has the new song, "Maybe," which sinuously expresses her dilemma of still wanting to love a briefly unfaithful husband. The show starts a bit tentatively, until it’s established that Kim is a girl from the country who’s lost everything and will always depend on the kindness of strangers and the roughness of clients. It’s from that fate that Chris saves her in their one night of love.

The tender wedding ritual is nicely done with lights and lanterns, but you can’t get Puccini’s infinitely superior "humming chorus" out of your head. There’s a lot of huff and puff in the crowd scenes, and the nightclub gyrations and sexplicitness now seem a bit gratuitous (though it’s a neat and cheeky touch to have a Mormon wander into the show from another musical down the road).

Jon Jon Briones delivers the showstopper well enough, trading the padded rickshaw for a luxury limo as the chorus swap peaked peasant hats for high kicks and waistcoats and Red Square regimentation for an equally savagely drilled Busby Berkeley routine.

There was a degree of snivelling around me in the last scene; I was too busy marvelling at the simplicity and grace of Noblezada’s performance to join in. And I do wish Connor hadn’t incorporated one of Hytner’s few bad ideas, the film of abandoned Vietnamese children to tug the heart strings during the perfectly sufficient anthem that accompanies the Atlanta conference, very well sung by Hugh Maynard.