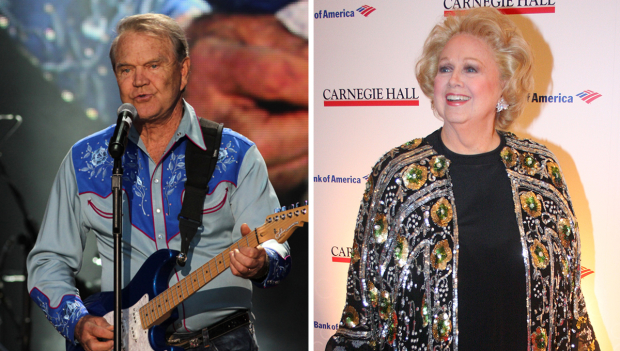

What Barbara Cook had in common with Glen Campbell

It’s probably a sign of getting older, but I have started to argue with obituaries. Take the hagiographic coverage of the death of Glen Campbell. "He was never that cool," I shouted at the radio, overwhelmed by the distinct memory of the fact that the Rhinestone Cowboy was someone your parents liked and knowing the words of "Wichita Lineman" or "By the Time I Get to Phoenix" didn’t mark you out as one of the in-crowd.

But perhaps I just arrived with him too late; he’d gone through fashionable and out again by the time I was listening to the songs. And loving them. Whereas I felt I discovered Barbara Cook at precisely the right moment.

Her death at the age of 89 was announced on the same day as Campbell’s and was completely obliterated by it in terms of news coverage. Yet this was possibly also because as Michael Coveney pointed out in his Guardian obituary, Cook was a figure "whose status was cultish rather than flagrantly popular".

I entirely missed her heyday in the '50s and '60s, when she became a Broadway star, most notably as the uptight librarian in The Music Man (a cult musical if ever there was one) and more intriguingly as the ingénue in Leonard Bernstein’s Candide (there’s a brilliant interview of her discussing the technical accomplishment that part required with the opera singer Renée Fleming in Opera News, if you’re interested).

I almost missed her comeback, when after years of alcoholism and a decline so precipitous that she was stealing packed meat from supermarkets, the pianist Wally Harper induced her to remember her talent and start singing again on the cabaret circuit in the late 1970s. But I caught her when, in 1985 at the age of 58, she played Sally in the concert version of Follies (opposite the much-missed Lee Remick and Mandy Patinkin, who has now found wider fame in Homeland).

She sang "Losing My Mind" in a voice so easy and fine, so drenched with suppressed emotion, so clear yet so full of longing, and I was hooked. Many happy evenings of seeing her in concert followed, as she sang on into her eighties, her voice deepening but the resonance of her performance never diminishing.

What strikes me about Cook – and Campbell come to that – is that their supreme musicianship was laid at the service of other people’s songs. The songs of Campbell that I love best were all written by Jimmy Webb (one of my great song-writing heroes) yet the meaning he gave them made them feel as if they belonged to him.

It was the same with Cook. The entire American songbook belonged to her; she could hit the heart both of the feeling and the balance in every song she sang. To hear her perform her party piece "Ice Cream" was a lifetime’s experience in itself. But it was the same with "If Love Were All", Noel Coward’s melancholy ballad of loss and longing which she transmuted from something light into something incredibly profound, or the way throughout her career she made Comden and Green’s "Long Before I Knew You" into a gentle cry of love.

In our culture we tend to revere the singer/songwriter, the person who can turn their raw experience into a song. Yet that underestimates the craftsmanship, the sheer artistic genius of the very best songwriters. If Girl From the North Country proves anything, it is that the real sign of greatness in a song is that it can escape its specific context and be given new meaning and power when placed in the hands and the vocal chords of others.

Cook was a supreme interpreter of other people’s songs. She made them live and breathe in new and always wonderful ways. I had already started to miss her performances but I shall cherish her recorded output for a very long time to come.