Sarah Crompton: Beckett's writing liberates women

© Manuel Harlan

When Lisa Dwan first performed Samuel Beckett’s Not I in 2005 she remembers Michael Coveney suggesting in WhatsOnStage, that it would spoil her for anything else.

"I remember thinking don’t be daft. I am just an actor on my journey. But actually he was right," she says, sitting in her dressing room at the Old Vic, about to rehearse No’s Knife, her own adaptation of the story collection Texts for Nothing. The production sprang from her longing to return to the richness of Beckett’s world once more.

"Doing Beckett, playing the subconscious, having a landscape as vast as that where you get to step out of every preconceived notion of what a woman is and get to be air and bird and mother and daughter and wind and element and father and son and sea and country and continent, and then to go back and play someone’s girlfriend or their wife or their mother, it’s hard. It’s corroding.

"Your whole body is telling you this is a lie, this is some man’s bullshit to keep you in your cage."

After performing Beckett, it's hard to play someone’s girlfriend or their wife or their mother. It’s corroding

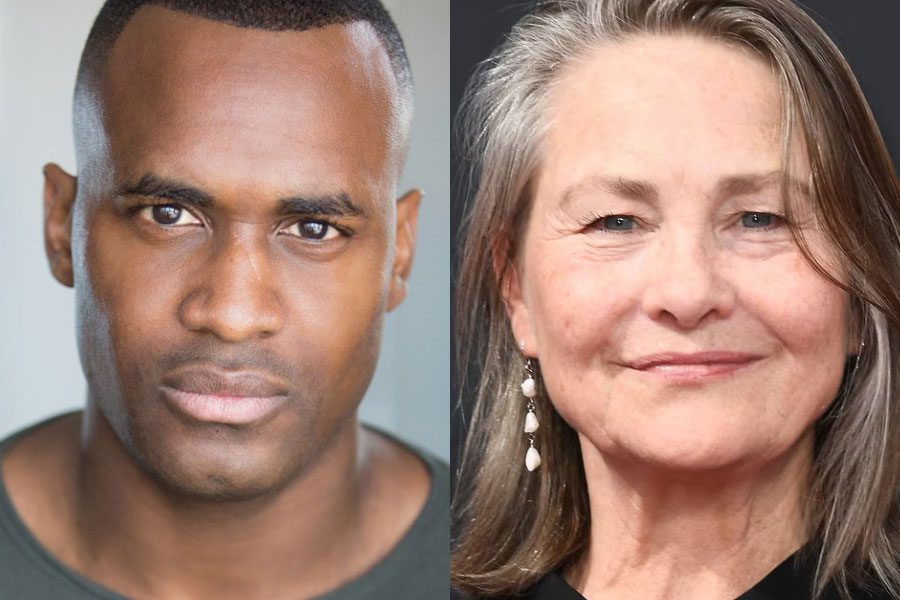

They are strong words but Dwan feels them passionately. Tiny, blonde and blue-eyed, she has spent her career fighting people’s preconceptions – and her astonishing performance in Not I broke every bond that had tied her. She practised for it obsessively, blindfolding herself to give herself the sense of becoming simply a mouth in the dark, tying her head to her banisters to understand the immobility required. The result was revelatory and the triple bill of Not I, Footfalls and Rockaby that she went on to perform established her as an important interpreter of the great Irish writer’s plays.

But when she looked for the next part, there was nothing. "So what was I to do? Wait for Happy Days?" Instead Edward Beckett, Samuel’s nephew and executor of his estate, suggested she look at Texts for Nothing. "My first thought was this is impossible. The problem of course is what you do with the body, how do you impose a theatrical setting on this prose?"

Her answer has been formulated with the help of co-director Joe Murphy, designer Christopher Oram, the lighting designer Hugh Vanstone and Lucy Hind’s movement direction. But what Dwan returns to is the simple power of Beckett’s text – what she calls his score. "Some people say they find late Beckett, the bit I discovered him through, very stark. They prefer the more gregarious early Beckett of Waiting for Godot and Happy Days.

"This is the in between place, an entry point into late Beckett, to putting the mind on stage. An entry point into the loneliness." She says as she performs it she thinks not only of her own personal wounds – all the ‘nos’ she has endured in her life, and that still haunt her – but also "all the souls buried down there who never got a chance to be anything." She thinks of the bodies discovered in the bogs of Ireland, the women who have been oppressed, the men who died in Flanders, the immigrants drowned as they seek sanctuary in Europe. The richness of possibility conjured by his deep, dark words is what she finds so powerful in Beckett.

Beckett's writing liberates women into an exploration of huge worlds of suffering and grief, hope and human defiance

Talking to Dwan, I found myself thinking about Harold Pinter’s No Man's Land, which I’d just seen at Wyndham’s Theatre starring Ian McKellen and Patrick Stewart – recently also twinned in Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, of course. I didn’t like the production as much as some, but I was struck again by the way the play is capable of such resonance, full of suggestive power about all kinds of themes.

The difference is that although I can just about imagine it being played by a quartet of women and yielding insight, Pinter’s themes are so intricately linked to the violence of men and the unknowability of women, that it is a difficult leap.

Beckett accommodates a much more universal view. Dwan believes that although men such as McKellen and Stewart and Patrick McGee have made huge impact in the works of Beckett, "his greatest treats were hidden in his female characters. His most painful truths were hidden there." Billie Whitelaw was perhaps his greatest interpreter and muse.

In this way, although Beckett may be agonising to perform, his writing liberates women into an exploration of huge worlds of suffering and grief, hope and human defiance. Which is a long and rewarding way away from playing the wife, the girlfriend, the mother or the psycho.

No's Knife runs at the Old Vic from 1 to 15 October, with previews from 29 September.