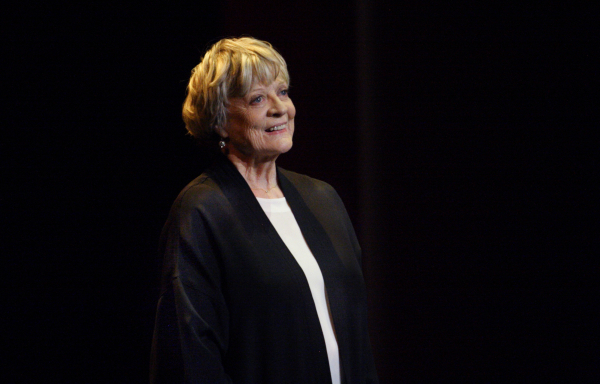

Michael Coveney: Maggie Smith comes up to date as two Nicks redefine the West End

(© Catherine Ashmore)

The excitement of having a new book published – my new Maggie Smith biography on 3 September, from Weidenfeld & Nicolson, also on Kindle, and as an audio book (read by the glorious Siãn Thomas, who appeared with Maggie and Eileen Atkins in Edward Albee's A Delicate Balance at the Haymarket in 1997) – is compounded by the fact that two of the theatre folk I most admire – Michael Billington and David Hare – are publishing books on the very same day.

I'll return to those books next week – Billington is anatomising the 101 greatest plays from Aeschylus to Mike Bartlett, Hare his involvement in the early days of the fringe in The Blue Touch Paper (as in "light the…") – but must first explain to WOS readers why I've returned to Maggie Smith having first written a book about her over 20 years ago, partly at her second husband Beverley Cross's behest, partly because a publisher wanted to know why there wasn't a book about her to date and could I fix one.

This most private, most generally admired and most enigmatic of actors, has had an astonishing, relatively unrecorded career, despite some brilliant critical writing (by Ronald Bryden, Tynan, Billington, Paul Taylor and others) and first unseen drafts of longer studies by film critic Penelope Gilliatt (one of John Osborne's wives) and Tynan, who died of emphysema after sketching out a proposed New Yorker profile. So I felt a sort of duty, especially as Maggie's dad, a Geordie lab technician, wanted me to use his comprehensive archive – a dozen bulging scrap books – documenting his daughter's career from West End revue to Oscar-winning movie stardom and the first National Theatre company.

As in all the books I've written, I saw Maggie as a gateway to writing history, both defying the ephemeral transience of theatrical performance and contextualising a great career in the onward flow of the living British theatre and cinema. I curated a BFI season of her films last year to mark her 80th birthday – "You're digging me up again," was her caustic comment; first time round, I was her "premature obituarist," so now I'm a necrophiliac – and the BFI wanted to sell the book in their shop; it was out of print. So, after a few discussions, an updated, re-written and totally overhauled version was suddenly on the cards.

It's been a joy and a rollercoaster: not only have I sat down and watched every Harry Potter movie (including the one she's not in) and every single episode of Downton Abbey, I've caught up with the other 20 films (four with Kristin Scott Thomas, the only actor I've tried and failed to interview!) she's made in the interim – I think Deborah Warner's The Last September and Dustin Hoffman's Quartet are my favourites – and I've been able to adjust and elaborate my sights on her fantastic work with Alan Bennett and Edward Albee, contrasting mother-fixated soul-mates blessed by her comic high-style genius.

And now she's going to be everywhere yet again: Downton Abbey, the biggest global export in television history, airs for the sixth and last series at the end of next month. And her latest movie, Alan Bennett's The Lady in the Van, directed by Nicholas Hytner, premieres in November; the Dowager Countess of Grantham, Lady Violet, has parked her van as a smelly tramp, Miss Shepherd, on Bennett's front lawn – she has literally gone from riches to rags.

Maggie herself, of course, will be lying low through all the brouhaha. She fears exposure and she fears the inevitable misrepresentations. Already, the Daily Mail, generously featuring the biography as their book of the week (and Peter Firth will be reading it on BBC Radio 4 as their book of the week starting 7 September) have erroneously asserted in online sub-heads (not in Roger Lewis's review) that Maggie met Kenneth Williams after she made her signature film, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (they had worked in revue together ten years previously), and that Lady Violet is modelled on Williams, which she's not, even remotely.

© Helen Maybanks

Hytner and Bennett have loomed large in her life these past 20 years, and maybe the new theatre the two Nicks – Hytner and Starr; we call them the NHS at WOS – are launching by Tower Bridge in 2017 will mark her final farewell to the stage in a new play written for her by Bennett. What a coup that would be, and a confirmation that the NHS enterprise is the final validation of a momentously shifting landscape in London theatre. Hytner says they will be mostly doing new plays: but so is everyone else, and will his initiative leave the National and the Royal Court scrapping for leftovers?

The "old" West End, of which, you could argue, Maggie was the last bona fide above-the-title box office star (though the first-in-a-lifetime flop she endured in Albee's brilliant The Lady from Dubuque at the Haymarket in 2007 left its scar; her audience didn't like her absence from the stage until just before the interval, and they didn't want to know about people dying of cancer), has long yielded precedence to the incoming dynamic energy of the companies formed by Michael Grandage, Jamie Lloyd and now Kenneth Branagh.

But these are temporary arrangements. And they are not offering all that much for the coach parties. The two Nicks threaten to join the new West End diaspora of the Old Vic under Matthew Warchus, the Almeida under Rupert Goold, the Donmar Warehouse under Josie Rourke, the Menier Chocolate Factory under David Babani and the Young Vic under David Lan: that's the new "West End" – and not even Cameron Mackintosh at the re-built Ambassadors (local politicians permitting) or Nica Burns in her new Charing Cross Road venue (not heard much about that lately) will be able to compete on artistic terms and adventurism.