Can casting ever really be colourblind?

© Johan Persson

Another week, another report into British theatre’s diversity problem; this time from the Andrew Lloyd Webber Foundation. Its take home message is simple – it’s a systemic issue. Fixing it isn’t. It will take attention and action at every level of the industry, from drama school intakes to artistic directorships, to ensure the art form is truly representative.

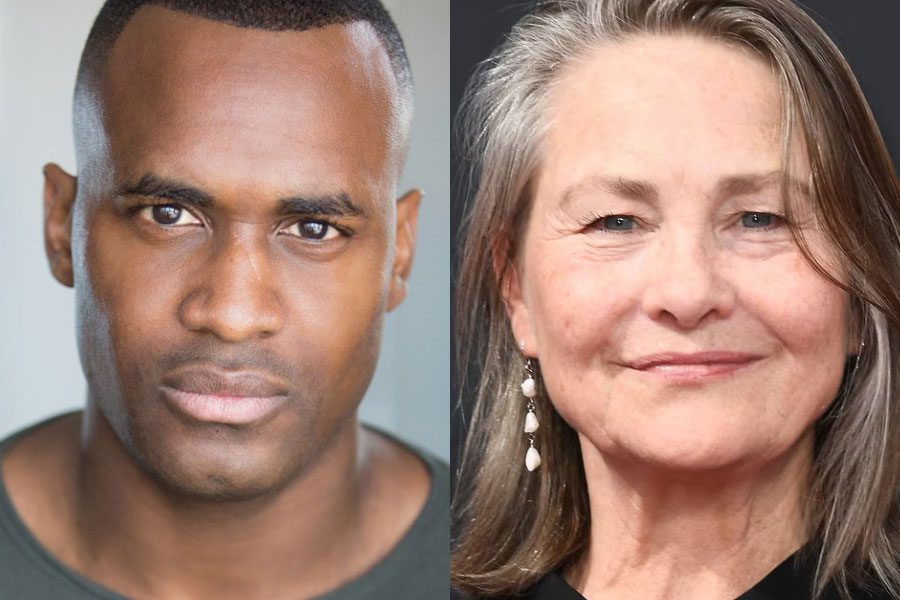

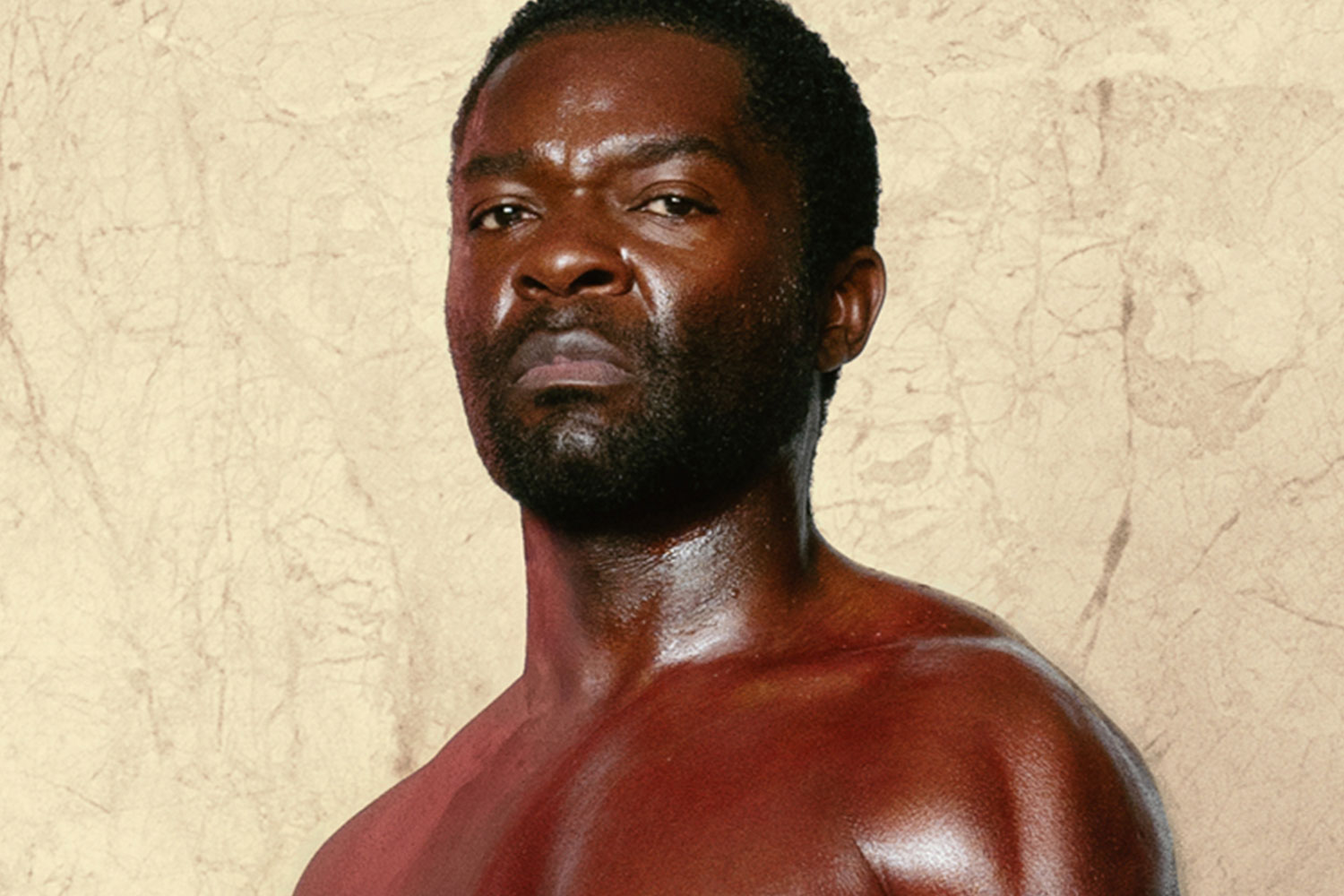

The report contains an interview with Show Boat star Emmanuel Kojo. "I have never identified as a Black Actor, I have always just thought of myself as an actor," he says. "We won’t be equal until there is no prefix when people talk about us."

He’s right, of course, just as he is in laying out a straightforward solution – "employing the best person for the job, no matter what their colour is."

However, the problem is only that simple in theory. In practice, it means shifting something outside the industry’s control – audiences.

Theatre is a representative space. Plastic bottles, as Peter Brook said, can becomes rockets that take you to Venus

Earlier this year, my dad went to see The Deep Blue Sea at the National. For all he loved it – rightly so – he came back with a question. Why had Adetomiwa Edun been cast as Freddie’s friend Jessie Jackson? He’s right that there weren’t many black ex-public schoolboys golfing at Sunningdale in the 1950s – though that’s not to say there were none – so, he wondered, was the director making a particular point or just casting the best person for the job, no matter their colour?

In September, the Telegraph critic Dominic Cavendish drew fire for his review of A Streetcar Named Desire at the Royal Exchange. In it, he questioned casting Maxine Peake and Sharon Duncan Brewster as the DuBois sisters. "The two are evidently not ‘related’," he wrote (in haste). "Go figure." The twitteratti duly took him to task for the phrase.

That thought has been echoed in letters published in The Stage this year, questioning casting in the RSC’s King Lear – specifically, how can he have two white daughters and one black? "Is there anything in the text to suggest that Lear had two wives, of differing racial origins?" asked one. You might reply, is there anything to suggest otherwise? Another letter entertained the idea, growing distracted by the implications: "How many times had Lear married? Was his daughter born out of wedlock?"

Aside from the fact that all these instances are entirely conceivable (and therefore unproblematic), the problem arises from the way these people are watching their theatre – that is, literally. They assume that an actor’s race confers the same race onto their character. So black actors play black characters and white actors, white, regardless of whether race is specified or relevant.

I don’t buy that. Theatre is a representative space. Plastic bottles, as Peter Brook said, can becomes rockets that take you to Venus. Theatre’s not a literal art form. It functions not by equivalence, but by likenesses – and people are people are people. People can play dogs and dragons onstage. They can sure as hell transcend the question of race.

However, watching Streetcar, I was confused too. Not as to how these two DuBoises were sisters – the text says as much, so I took that as read. In those terms, race wasn’t significant – but I couldn’t work out whether it had some other significance.

Stella DuBois is the daughter of a plantation owner, after all. She’s turned her back on the family estate and wealth that would have been built on the back of slavery. Casting a black actress in the role opens interpretations that casting a white actress wouldn’t have done.

Here’s the real problem: white is still presented as neutral onstage

Put it this way: Was director Sarah Frankcom making a particular point? Or was she simply casting the best performer for the part? Was race significant or not? It’s the same question my dad asked of The Deep Blue Sea.

Neither production made it entirely clear. Streetcar wasn’t colourblind – the three Day of the Dead-style figures were played by actors of colour – and nor, with its three white leads, was The Deep Blue Sea.

When we come across colourblind casting, we don’t suddenly become blind to race. We still see colour onstage, be it black or white or anything else. The question is whether we, as an audience, ought to read anything into it and it is the production’s job to help us out. Colourblind casting isn’t enough on its own. It has to flag that itself as such.

Here’s the real problem: white is still presented as neutral onstage. It is taken as the colour without connotations; the blank canvas on which other signifiers can be hung; the norm from which anything else deviates.

Theatre has to disrupt that, and the only way to do so is to have truly mixed casting. It’s not enough, in other words, to just give the best actor the part, regardless of race, as Kojo insists. We have to actively ensure diversity on our stages. We need to make that the norm.