The Lemon Table review – Ian McDiarmid tackles Julian Barnes' stories in a two-part solo turn

© Marc Brenner

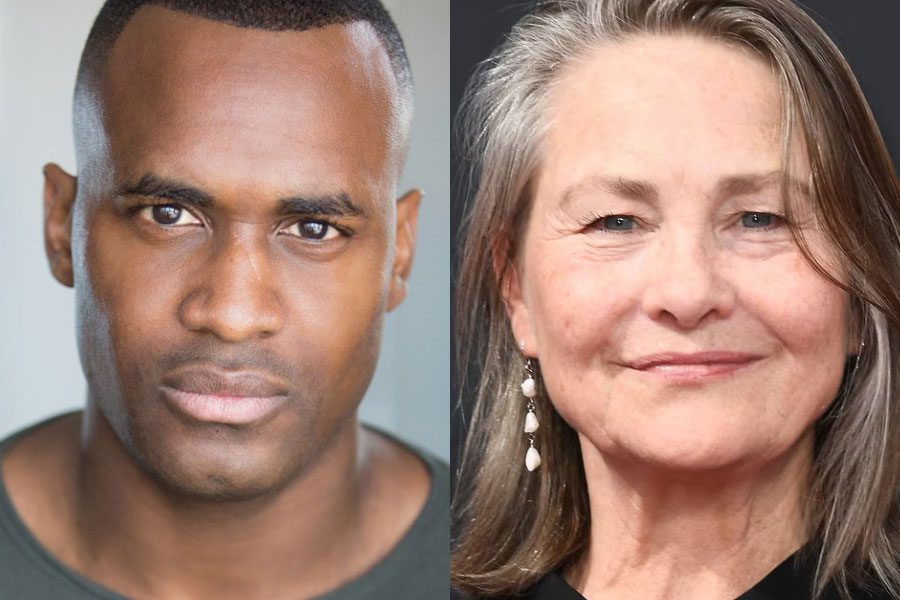

Ian McDiarmid has dramatised two monologues from The Lemon Table, Julian Barnes' 2005 book of short stories and first-person accounts exploring what it is to grow old. Both feature older men and at first sight, that is all they have in common.

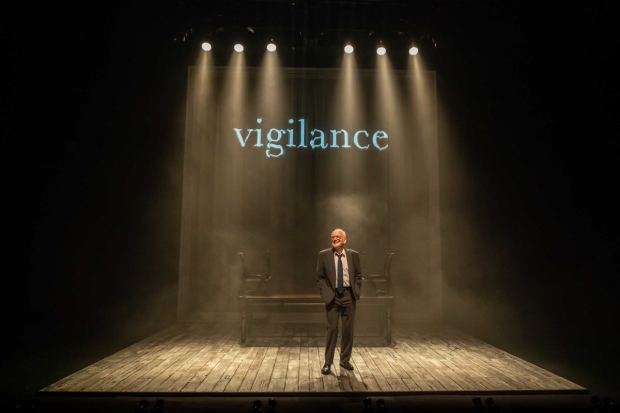

The speaker in "Vigilance", the first, is a rather gobby self-righteous chap, an ardent classical music fan, who shares here with an audience he addresses as his peers, his exasperation with the fellow concertgoers who ruin his experience by talking, shuffling, coughing, sneezing, programme page-turning, failing to silence their digital watches – he could and does go on. Exasperation is putting it mildly, for he clearly holds these transgressives in utter contempt. He relates how he pokes the occupier of the seat in front of him to silence him with a fierce glare and pointedly hands out cough sweets to offenders. But his virtue-signalling quickly descends into slagging them off and even pursuing them at the interval, stalking them with what he hopes is an air of authority that will lead his targets to think he has an official position. He apparently sees the conductor, here Bernard Haitink, as his soulmate and trumpets his (genuine) knowledge of the music and composers he clearly knows and loves.

McDiarmid earns plenty of laughter, but he also gives a rounded account of the man, who now gives a telling glimpse into his home life. Here, his partner Andrew gives him a reality check, reminding him that composers commissioned by royal courts would have been resigned to their work being destined to be background music to the social business of eating and flirting. Andrew thinks he should stay home and listen to his stereo system. McDiarmid clearly relishes his retort with a vivid and eloquent championing in defence of listening live in the concert hall with "a hundred or more musicians going at full tilt in front of you".

The complications and frustrations of his long relationship with Andrew are revealed with the subtlety you would expect of Barnes. It's clear that both of these men have their eccentricities, getting more marked as they grow older. Cyclist Andrew habitually navigates rush hour traffic listening to novels through his headphones and making detours to collect firewood. His own bugbear is unheeding motorists and his language describing the objects of his opprobrium is colourful, to say the least, with liberal, enthusiastic application of the ‘c' word – to his male targets at any rate …

© Marc Brenner

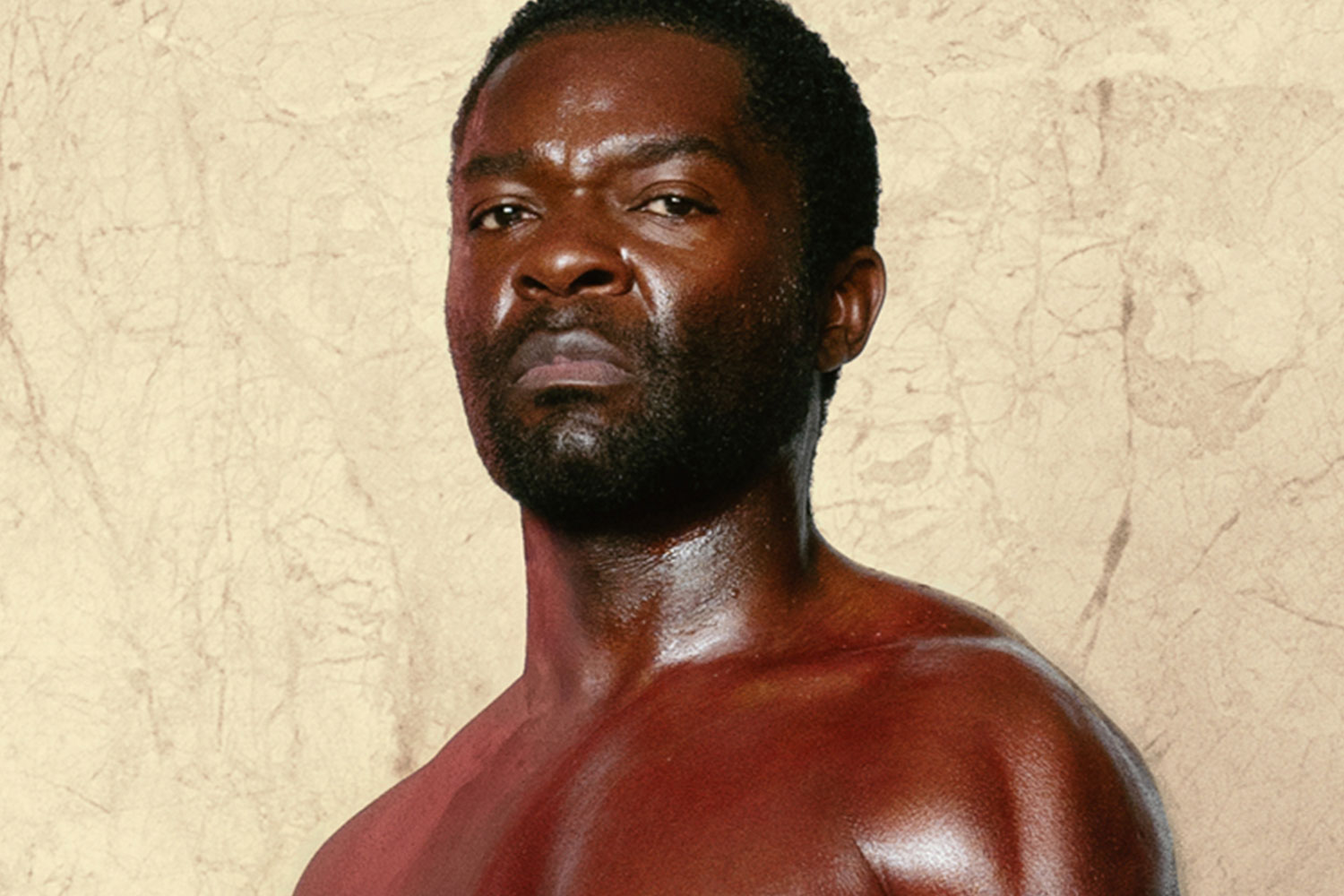

It emerges that Andrew works in the furniture department at the V and A and indeed the table at which McDiarmid is seated to share his story is clearly a cherished piece. The table also provides a link to the second monologue, "The Silence". Seated at it now is Sibelius, Finland's most famous composer, clearly in the winter of his life. The title is apt, for the great man speaks from the peace of his beloved retreat deep in the Finnish countryside, where he lives with his wife Aino. He describes the extraordinary pleasure he derives from his love of the woods around his home and especially the birds that populate the skies above. The first confidence he shares is his longing to see the rarer flight of the cranes as well as the more common wild geese. "Geese would be beautiful if cranes did not exist" he opines.

Like our frustrated concertgoer though, he is constantly infuriated by the 'noise', of interruptions as the world outside intrudes. He is spooked by the fear of ageism, personified by the ignorance of a brash young journalist unaware that his music had been used in the iconic film The Jazz Singer. He describes "the ignorance of the young" as "a kind of silence".

He is also clearly nettled by criticism, which leads to insights into the intricacies of composing, enlarging on the knowledge displayed by the concertgoer in the first piece. Again, his metaphor is poignantly revealing "Music begins where words cease…What happens when music ceases? Silence … What does music aspire to? Silence."

Delicately some detail of his domestic life emerges: the devotion – and frustration – of Aino, his wife of 65 years and mother of his five surviving children; his forbidding them to sing or play music themselves and his feelings of guilt for neglecting Aino for his music – and alcohol "now my most faithful companion." He is also ashamed of shortcomings in his professional life, often down to his alcohol addiction. His musings are full of intimations of mortality: "My journey is nearly complete … The logic of music leads to silence"; and here laced with dark humour "Cheer up! Death is 'round the corner."

Now, finally, the significance of the title emerges. He and his male friends meet to dine and talk about death at what he calls "the lemon table", so named because in China "the lemon is the symbol of death." His own death is linked to his longing to see the cranes to which he returns at intervals and is heralded by the return of these "Birds of my youth" at the climax of this beautiful elegiac piece that so perfectly complements the first in this meditation on age and death.

McDiarmid's close and old friend Michael Grandage and Titas Halder share the direction with great empathy. The creative team stage designer, Frankie Bradshaw, lighting Paule Constable and sound Ella Wahlström fully realise a joint sensory vision, which of course includes the music, the link between the two monologues. Particularly effective is Bradshaw's evocation of the paintings of Danish artist Vilhelm Hammershoi, a contemporary of Sibelius, from whom she takes her inspiration.

The painter's muted monochrome greys are echoed in the colour of the huge table at which McDiarmid is seated and indeed the subtle shades of grey in his outfit. A huge version of the simple frames glimpsed on the walls of his interiors provides a backdrop to foreground McDiarmid's virtuoso performance, a wonderfully three-dimensional account of Barnes' meditation on old age that justly brought the audience to its feet at its climax.