Standing at the Sky’s Edge review – a soaring achievement with new edges for the West End

The hit musical is as brilliant as ever as it moves to the Gillian Lynne Theatre

I’ve never seen a musical’s romantic ending so hotly debated as that of Standing at the Sky’s Edge. Streams of people, funnelling out of the Gillian Lynne (just as they did last year during the show’s run at the National Theatre, and likely at its two previous runs at national portfolio venue, Sheffield’s Crucible Theatre), either mightily miffed or wholeheartedly on board with Chris Bush’s choices.

Bush, sure to be one of the most exciting playwrights around, has pieced together a tightly wrought tapestry of intergenerational harmony and conflict. The setting – a single flat in the Park Hill Estate, where a variety of different inhabitants play out their lives, thrown about by history like flotsam. Three hours, six decades, a soundtrack of numbers by famed Sheffield artist Richard Hawley.

In Bush’s hands, the vast, brutalist estate, now a south Yorkshire landmark, is a microcosm – a symbol for post-war optimism, the promise of a welfare state, as well as the backdrop for decimation of industry during the 1980s, before the rampant gentrification that brings us to the present day. But rather than being a “state-of-the-nation” epic, Bush makes sure it’s the individual characters that are placed front and centre – scenes hop backwards and forwards between the decades, washing over one another as the years coalesce and contrast.

The earliest Park Hill inhabitants are Harry (Joel Harper-Jackson), the youngest foreman on a steelworks about to encounter the wave of industrial decline from the 1970s, and his stern, unwavering wife Rose (Rachael Wooding). Flashforward a couple of decades and the flat is occupied by Grace (Sharlene Hector), George (Baker Mukasa) and their niece Joy (Elizabeth Ayodele), all three escaping civil war – with Joy also catching the eye of local lad Jimmy (Samuel Jordan). Finally, Bush hops over into the present millennium to alight on southerner Poppy (Laura Pitt-Pulford), a woman escaping her own past in order to find some semblance of emotional security in the newly redeveloped building.

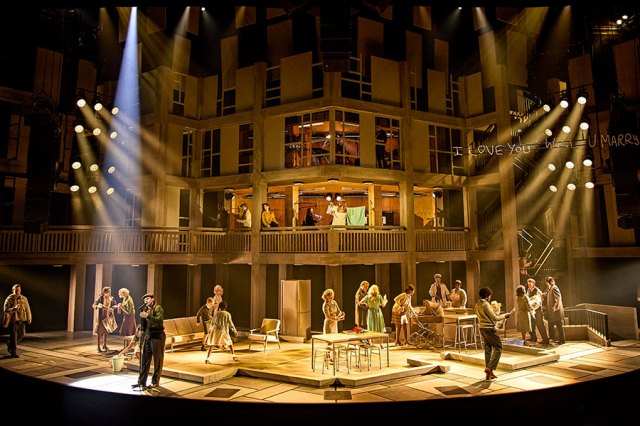

All of this plays out on the immense, colossal backdrop of Ben Stones’ set – brutalist concrete beams clawing towards the ceiling as if attempting to break through to the clouds beyond. Compared to the cavernous Olivier stage, where the show last played in London, the slightly more intimate confines of the Gillian Lynne make the experience feel more like an embrace – the audience almost peering over the flat and into the hearts and minds of its residents.

The show’s critical clout is indisputable at this point – with two Olivier Awards, a South Bank Sky Arts Award and even a registered trademark status to its name, Sky’s Edge is soaring its way to the status as one of the most well-received musicals produced on these shores in many decades.

Featuring the I Love You Bridge, © Jason Lowe, 2001

Under Robert Hastie’s direction, the streets are paved with ghosts – figures from the past, present and future flit between columns and dance along silently – their spectral form silhouetted by Mark Henderson’s lighting. A large ensemble allows Park Hill to breathe – crowds surge from the shadows during moments of unfettered elation, or stand sentinel as they watch miners head towards their final shifts.

As much as Hawley’s tunes are cracking earworms, much of the praise must go to orchestrator, arranger and originating music supervisor Tom Deering, who has refashioned them into richly crafted musical numbers, aided no end by sound designer Bobby Aitken. I’d dare anyone not to be moved by the emotional oomph of Wooding’s delivery of “After the Rain”, or stirred by the chaotic climax of “There’s A Storm A-Comin’” to close out the first act.

It’s a testament to Bush’s writing – including that controversial conclusion to one of the narrative arcs – that, in a relatively re-cast ensemble (kudos to casting directors Stuart Burt and Chloe Blake), the characters feel freshly portrayed, with new edges compared to the production’s previous run. Pitt-Pulford’s Poppy shines with glimmers of melancholy around the eyes, while Lauryn Redding’s Nikki, who arrives bold as brass late in act one, is more bumblingly comedic than the character’s portrayal at the National. Ayodele’s Joy, who goes on one of the largest emotional journeys of anyone, emerges as the emotional heart of the piece, while Jordan seems to have found even greater depths to Jimmy’s heartwrenching backstory.

Provoking fevered reactions – many audible gasps or sobs were heard after a variety of plot beats – while being resolutely, brazenly assured in its craft, makes Standing at the Sky’s Edge a towering feat of contemporary musical theatre. It stands as a shining tribute to the combined power of both popular music and stage storytelling, and subsidised and commercial theatre. Unmissable.