Sarah Crompton's verdict on the Oliviers: 'Awards ceremonies are curious things'

Crompton reflects on a record-setting night at the Olivier

© Photo by Jeff Spicer/Getty Images for SOLT

This has been a lively awards season one way and another, brought to its conclusion by the Olivier Awards handed out last night. I was particularly pleased in the midst of it to be asked to present the Trewin Shakespeare award to Cush Jumbo for her performance as Hamlet at the Young Vic at the Critics' Circle Theatre Awards. I felt very strongly that it was an astonishing achievement, which swept aside all considerations about its historic nature (the first Black female in a major London production) and was instead the most direct and heartfelt contemporary version of Shakespeare's Prince.

At the Royal Albert Hall, admittedly in a slightly different category, Jumbo didn't win, and the prize went instead to the equally wondrous Sheila Atim. I am sure that the voters didn't want to put down Jumbo's performance in any way; a majority of them just admired Atim more. That's the thing about prizes. In the end, they come down to personal taste (just tell the makers of The Power of the Dog, beaten at the Oscars by the more audience-friendly CODA).

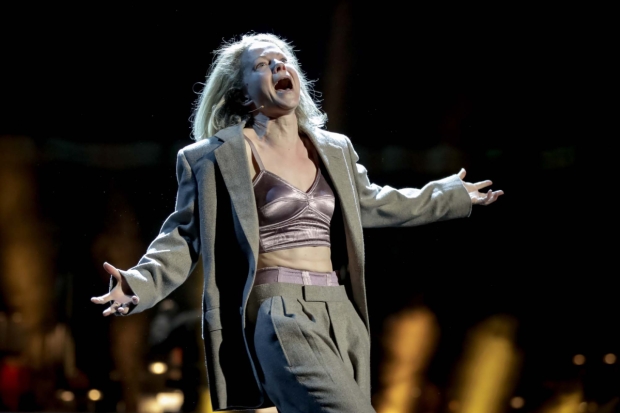

For myself, I was glad it was Cabaret's night, sweeping up seven awards. I loved that production, those performances, that show. It's easy to see Cabaret as a commercial juggernaut, sweeping all before it, with luxury casting (Oscar-winner Eddie Redmayne as the Emcee, Oscar-nominated Jessie Buckley as Sally) but what I most admire about the production is its integrity.

© Christie Goodwin

The idea for the revival was Redmayne's (he told a very funny story at the awards about casting himself and then having a crisis of confidence) and the producers threw in the commitment to transform the Playhouse Theatre into the Kit Kat club. But then director Rebecca Frecknall, designer Tom Scutt and the entire Cabaret team carried out a radical rethinking of how a musical, written in 1966, could be reconfigured so that it spoke just as strongly to a different age. They wanted to find the essence beyond its fame.

I happened to interview Frecknall very near the start of the process, before she had even gone into rehearsal, and it was clear then how rigorous she was being in her work around the show, how she wanted to emphasise the way in which the rich diversity of Berlin was stamped out by the rise of the Nazis and be faithful both to that and to its echoes in the world around us.

From the beginning, she was clear that this is a musical about people being blinded by illusion: Sally believes she is a great star, Cliff, her accidental lover, believes he is straight and can set up a home with her and a baby; Herr Schultz, the gentle greengrocer believes the threat to the Jews will go away. Only the Emcee perhaps sees clearly.

For Frecknall, in her rethinking of the story, the savage heart of the show then becomes Fraulein Schneider's accusatory "What Would You Do?", a direct appeal to the audience to ask themselves how they would choose when faced with the moral dilemmas that the rise of Hitler posed. The production makes this question resound by deliberately stripping away the familiar Nazi iconography of red and black and revealing that conformity and bending to the will of oppressive authority, can also be beige and bland, and sneak up on you almost without you realising it.

Four of the original performances in the production were rewarded with Oliviers – Buckley for her spine-chilling Sally, Redmayne for the shape-shifting Emcee, Elliot Levey for his delicately rumpled Schultz, Lisa Sadovy for her tragic Schneider. They were all magnificently deserving of their awards. But when I returned to Cabaret the other evening, only Levey was still in the same role.

Yet the production has lost none of its power to disturb and challenge. Fra Fee and Amy Lennox find different beats in their interpretations of the Emcee and Sally; Omar Baroud as Cliff and Vivien Parry as Schneider shape new emotional journeys for their characters. It feels different, but essentially the same. Seeing it with a new cast and fresh eyes, it is clear that this version of Cabaret is as defining and important in its own way as Sam Mendes's influential 1990s revivals.

That production made the journey from London to New York – one that you feel the Frecknall's all-conquering vision is likely to repeat.