Review: The Starry Messenger (Wyndham's Theatre)

© Marc Brenner

Writer Kenneth Lonergan is the poet of the unconsidered, the observer of the small, significant moment that might barely trouble a butterfly's wing when it happens, but has enormous, rippling repercussions. In plays such as This is Our Youth, The Waverley Gallery and in screenplays such as Manchester by the Sea, he looks long and gently at ordinary lives and draws out general truths.

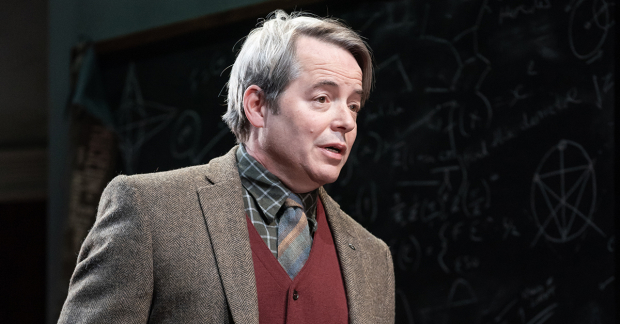

He and the actor Matthew Broderick have been friends since they were 15 and Lonergan wrote this play about a man's mid-life crisis for him. Premiered off-Broadway a decade ago, it finally arrives in London to give the much-loved movie star his West End debut, playing opposite Elizabeth McGovern, best known as Cora Crawley in Downton Abbey. It is a quiet, funny and perceptive study of a certain type of uptight disappointment and emotional paralysis. And although it is baggy and contains a single, sensational plot twist that it doesn't justify, it is nevertheless hugely enjoyable.

Broderick is Mark, a lecturer in astronomy, teaching a class who don't quite want to be there in a Planetarium that is about to be shut down. (The play is in fact based on a lecturer Lonergan met with Broderick when they were both teenagers; its setting is the old New York Hayden Planetarium, which was indeed demolished in 1997.) He delivers his talks in a monotone that disguise the passion behind them; he has been inspired by astronomy, by the possibilities of the universe and the wonder of the night sky since he was a boy.

Yet now he feels trapped in a job he didn't want to take, and in a marriage to McGovern's Anne where "we don't talk about the cosmos, we talk about dry cleaning". He has a teenage son who plays the guitar badly in the basement and his only relationship with him is shouted down the stairs. One of his class asks pointless questions and – in a devastatingly funny scene – another offers a critique of his teaching methods. "I was going to give you a ‘Poor', but I realised that I might be being overly influenced by my personal taste."

It's inevitable then that when he meets Angela (Rosalind Eleazar), an open-faced and warm-hearted single parent 20 years younger than him, that he is going to fall for her. Their relationship has far-reaching consequences and raises all kinds of questions, asked quietly but insistently, about our place in the universe and our relationship with the divine.

Director Sam Yates lets all this unfold at its own unhurried pace on Chiara Stevenson's clever revolving set, which creates three distinct rooms, each with a great dome of changing sky overhead. Broderick's performance defines New English reticence; he is so buttoned-up and mild that sometimes he seems to have come to a halt. But he has perfect deadpan delivery and his eyes, warm and watchful, tell a story of his inner life.

McGovern has too little to do as Anne, the brittle wife, who worries about the arrangements for Christmas and the state of her marriage, but has lost the gift for listening, but she finds exactly the right tone of well-mannered niceness. The revelation, though, is Eleazar, as Angela, positively shining with life's possibilities, and a goodness rarely seen. The character is a nurse and her scenes with the dying, cantankerous Norman, played with a subtle mix of fear and impatience by Jim Norton, crackle with a life and passion that sometimes feels missing in the rest of the play.

Jenny Galloway and Sid Sagar also offer finely differentiated and beautifully timed turns as Mark's quizzical pupils, bringing out all the humour in this well-observed and humane play. It doesn't quite hit the heights, but it does – like the Planetarium in which it is set – offer a glimpse of them.