Review: The Lie (Menier Chocolate Factory)

Samantha Bond and Alexander Hanson star in Florian Zeller’s comedy about marriage and dishonesty

Which is the lie at the heart of The Lie? There are so many littered through Florian Zeller‘s latest post-modern boulevard comedy that it’s almost impossible to spot the fib singular – the eponymous porkie. Is it the first one told, or the first one we spot? Is there some ur-lie way back in the past? Or is everything we see a sham of some sort?

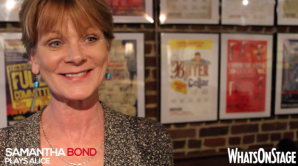

Zeller returns us to literary Paris – a soirée for four. Pompous Paul (Alexander Hanson) has bought in the finest of wines. His wife Alice (Samantha Bond) wants to cancel. She’s spotted their guest Michel kissing another woman and can’t bring herself to keep the truth from his wife, Laurence. Is it a lie to know and not tell? Alice circles overhead, dropping hints from on high.

Her discomfort triggers a marital crisis of its own. She extracts a confession of infidelity out of Paul, who quickly backpedals – "just a joke," he insists. Out for revenge, she plays the same trick. In doing so, all hell and hypocrisy breaks loose.

These are lies built on lies – a web of deceit. It’s almost a study in the species of lie, a grand classification of different untruths. There are lies of omission and tactful lies that mean well. Some are barefaced, others disguised beneath false noses and beards. For every lie that smuggles the truth out into the open, another is so see-through it has its own kind of honesty.

The point is that we end up not knowing what’s what, unable to tell truth from false. Therein lies Zeller’s trademark, teasing theatricality. The Frenchman uses theatre’s artifice to forge an aura of uncertainty. Just as The Father and The Mother twisted reality out of shape, The Lie‘s constant spinning does much the same. If everything’s untrustworthy, we can lie with impunity. But that’s theatre, isn’t it? To act is to lie. We suspend our disbelief.

Or do we? Because very little of The Lie rings true. Its characters exist for the purposes of the play – not people, but pawns. They follow the playwright’s logic, not their own, and the script seems schematic – parries and thrusts, reversals and reveals. It has the rhythms of a Rubik's Cube, a puzzle on rotate. In the end, none of it matters.

Theatre being theatre, the play must be self-contained. To satisfy, it needs a closed system; a situation that contains its own solution. Any illicit affair must be between those onstage (and this being boulevard comedy, we can rule out anything as 'risqué' as a same-sex relationship). It’s why the play works and why it doesn’t. The answer’s right in front of us all along. In teeing it up, The Lie lets us down. It’s tricksy.

Lindsay Posner’s production can’t do much to change that. It’s nimble enough to divert an audience with an inscrutable Bond and an unscrupulous Hanson, but it never cracks open the play’s deeper implications. A bolder director might make a case that this is the ultimate post-truth play. The moment marriage itself starts to seem like a sham, the whole pack of cards comes crumbling down – nice wines, good friends, all of civil society. Posner’s polite staging merely props it all up.

The Lie runs at the Menier Chocolate Factory until 18 November.