Player Kings review – Ian McKellen is masterful in a play of two halves

Shakespeare’s Henry IV plays are welded together in this West End production

Heavy is the head that wears the crown – a line Stormzy quoted from another era-defining poet, William Shakespeare. It’s a thought that sits right at the heart of Player Kings, Robert Icke’s marathon length mash-up of the two Henry IV plays, brought together for a spell in the West End following (and preceding) tour stops across England.

Charting Henry IV’s time on the throne – inherited under slightly dubious circumstances from Richard II, murdered unceremoniously while in prison – and the hijinks of his troublesome son Hal, the central two parts of the Henriad are certainly the least staged of the four, eschewed in favour of the more accessible and self-contained Richard II and Henry V.

Icke, with his traditional creative vigour, attempts to make the case for the pair by condensing and merging the two texts, while also marshalling a titanic cast of stage greats – led by the production’s biggest draw – stage royalty in the form of Ian McKellen as Shakespeare’s great buffoon John Falstaff.

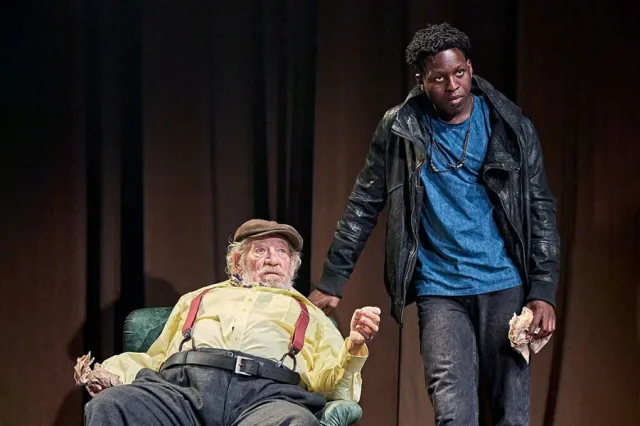

It’s worth saying this from the off – McKellen is magnificent (though when isn’t he). Trippingly, he dances through Falstaff’s lines with comedic and physical poise, trading barbs with the vagabond prince Hal one moment, before ruminating on his own mortality the next. He’s a walking paradox of a Falstaff – guzzling down sack or masticating his way through scenes, the man is lithe with his tongue yet ungainly with his comportment. Yet again, McKellen delivers one of the best stage performances of the year.

He’s matched cheek by jowl by Toheeb Jimoh’s Hal – first seen with bared arse, sniffing cocaine off a kinkily chained toyboy in a bawdy tavern. Jimoh, also magnificent in Rebecca Frecknall’s Romeo and Juliet last summer, is an enthralling presence – youthful and cheeky, prone to anger and mischief, while dabbling in fits of melancholy. He seems to stiffen as the show progresses, as if being invisibly corseted by the strictures and responsibilities of his imminent rule. His Henry V would be an excellent sequel, if ever staged.

The pair are assisted from some fantastic turns across a large company – Richard Coyle’s Henry IV is a man haunted by the past as he bemoans the future of his nation, while Samuel Edward-Cook is a charismatic, physically imposing martial presence as the revolutionary upstart Hotspur. As expected, it’s not a play that offers much for female roles – meaning the effervescent Clare Perkins feels underused as the steely and wronged tavern owner Mistress Quickly.

In his excisions and direction, Icke foregrounds the notion that the Henry IV plays are driven by three men each tormented by their self-loathing. From the moment he is crowned, Henry IV knows he has to visit the Holy Land in order to absolve himself of sin after the death of his predecessor (who haunts the stage in a brilliant turn from falsetto singer Henry Jenkinson) – a plan that never he is never able to properly see through. Hal is haunted by the tales of his nemesis Hotspur – with the northerner winning praise for his own skill at arms and ability to defend his nation from the Scots. The Prince of Wales channels his insecurity into jabs at his friends, merrymaking and petty theft, twice adopting the guise of others as if to escape from his own identity.

Falstaff, aged and surrounded by financial insecurity, watches as his life ebbs away, his last hope, his friendship with the Prince of Wales, serving as one last gamble. Out of all of these insecurities, war, bloodshed and death follow.

Icke introduces some masterful interventions – one towards the end of act one bringing forth audible gasps from the audience – heightening and deepening Hal’s torment. Icke focuses on the idea that the monarch is a fundamentally lonely figure – as Henry IV ends up alienating the very nobles that assisted his rise to power, so too does Hal cast aside his tavern friends as he ascends to the throne. A heavy head indeed.

But it all comes apart in a staid second half (shorter in length yet feeling longer), where both Shakespeare’s text and Icke’s choices feel much more lacklustre and uninspired. Without the urgent and imminent threat of civil war and insurrection, and with some strange directorial decisions (prostitute Mistress Tearsheet having an Eastern European accent felt particularly lazy), the wheels of Icke’s Shakespearean behemoth wobble as they scream out for voracity. Perfunctory design choices from Hildegard Bechtler, with the show’s aesthetics largely grounded in the early 20th century, don’t add anything too revelatory.

It falls to the cast to take the reins across two turbulent reigns – in what is an all-round assured and dab attempt to truncate a pair of Shakespeare’s bulky history plays, though not without a few shortcomings. There may be mighty players, but this occasionally feels like less than the sum of its parts.