Jesus Christ Superstar review – Ivo van Hove’s devastating take on the classic rock musical

The production is currently running at the DeLaMer Theater in Amsterdam before touring

British and American theatregoers who assumed that Timothy Sheader’s Regents Park-originated version of the classic rock opera was the ultimate modern reboot, hadn’t reckoned on Belgian visionary Ivo van Hove and his streamlined, devastating take on this beloved material.

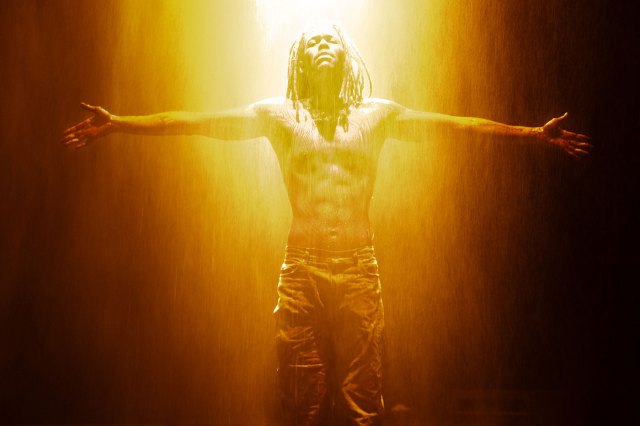

Where Sheader’s production, still touring the UK and USA, feels monumental, like a music festival on steroids and glitter, van Hove’s is intense and shocking, imbuing the familiar figures of Jesus, Judas, Mary and Pilate with an aching humanity, and the crowd of rabblerousers surrounding them with a disturbing volatility. As the earlier iteration paid tribute to the show’s rock album roots, this one feels politically driven, presenting a Christ (Jeangu Macrooy) who could be the leader of a present-day, anti-establishment movement, capturing the hearts, minds and possibly the libidos of the grungily cool youngsters who whirl and leap restlessly around him.

That both iterations work equally well is testament (pun intended) to the durability and sheer power of Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber’s early 1970s representation of the last week in the life of Jesus Christ. The show as a whole has a breathless excitement, a naivety even, captured definitively here, that bespeaks the youth of its creators (they were both well under the age of 30 when they worked on this), but also an ambition and open-heartedness that is never unaffecting. Rice’s lyrics are precise, caustic and sometimes quaintly of their time, while Lloyd Webber’s eclectic music remains utterly thrilling, mixing up unforgettable melodies with a bold, morbid discordancy that still takes the breath away with its sense of urgency and its unexpected inventiveness.

Under Ad van Dijk’s musical supervision, the score sounds astonishingly fresh, the earthshaking bombast of the more dramatic moments offset by a delicacy one doesn’t often associate with this piece. Tom Gibbons’s sound design is crystal clear, a bit of a rarity when theatrical rock is played live, so the harmonies and complex orchestrations register with real potency. It’s also worth noting that it’s performed entirely in English.

If it sounds lush and expansive, the visual aesthetic is stark and unforgiving, but also entirely successful. This troupe of youthful agitators, a diverse, sexually fluid bunch, disport, stagger and stomp on an enormous black platform with the audience on all sides (design by van Hove’s regular collaborator Jan Versweyveld, who also did the sculptural, transformative lighting). It’s all spine-tinglingly immediate but also threatening as the full company, hunched over and hooded, materialise out of the dry iced darkness at the opening to form a forbidding-looking mob before parting to reveal Luke Hamming’s disturbed, desperately vulnerable Judas to sing the rueful anthem of foreboding “Heaven on their Minds”.

Hamming is remarkable, slight of frame and possessed of a piercing falsetto pitched somewhere between quicksilver and a shriek of unimaginable pain, his ragged mop of hair concealing the face of a bewildered child. This is a Judas to haunt your dreams, one who dies not by hanging but by repeatedly hurling himself at the unyielding stage until he’s bloodied and broken. Macrooy’s charismatic Jesus is sweet and serene by comparison but tremendously moving when his facade cracks open in the famous “Gethsemane” number and he gives voice to his terror at the impending suffering ahead of him.

Edwin Jonker is a majestic, strapping Pilate, secure and in his power until his horrified realisation that the beaten, abused Jesus prone in front of him is the same man he’d dreamt about. Magtel de Laat radiates strength and heat as a stunning, compellingly modern Mary Magdalene and delivers a searing version of “I Don’t Know How To Love Him”.

Contemporary dance specialist Jan Martens has created the choreography, muscular and organic as befits a crowd of people reacting with their hearts and bodies rather than their heads to an extraordinary set of circumstances and personalities. Where Drew McOnie’s dances for Regent’s Park suggested a mob in thrall to external forces that they couldn’t comprehend, here the movement feels like inner turmoil bursting out of tensile bodies, channelled through their arched backs, undulating midriffs and clenched fists. It’s dynamic and extremely effective.

Having audience members on stage throughout, even participating in the Last Supper sacrament, makes colluders of all us onlookers, which begins as a fun novelty but becomes more and more discomfiting as the story hurtles towards its inevitable conclusion. It proves especially potent in Herod’s number, for once not the comedy relief despite lyrics like “prove to me that you’re no fool / walk across my swimming pool”, but instead a terrifying demonstration of power abuse, what used to be the dance break becoming instead a series of all-too-realistic snapshots of Alex Klaasen’s black-suited King performing acts of unendurable torture on a captive, distressed Jesus. It’s absolutely chilling. Van Hove’s decision to scrap the interval gives the musical a leaner, more coherent dramatic shape, and further ups the tension to the extent that when the ending comes, it’s almost a relief.

The overriding impression of this Jesus Christ Superstar, aside from the fact that it’s a darkly dazzling piece of entertainment, is that van Hove sees it as a parable about collective responsibility, and the dangers of blindly following the crowd. It’s not just the placing of some audience members right in the middle of the action, it’s also in the staging of the “Simon Zealotes” number which sees Jesus isolated on the floor while the rest of the company tower over him like a seething mass of humanity, at first benign but becoming increasingly maniacal and unmanageable. It’s there in the astonishing moment after Christ has destroyed the temple, and gargantuan wind turbines roar down from above driving flurries of dry ice and ill-gotten bank notes (sadly, all fake) all over the theatre, and in the ending, not dissimilar to the conclusion of van Hove’s epoch-making A View from the Bridge, which sees almost the whole cast united in incriminating bloodiness.

Tickets to the current Amsterdam season have, unsurprisingly, all sold out now, but the production is touring all over the Netherlands before returning there in August. If you love this show, I strongly advise you to see it. Exhilarating, troubling stuff, and perhaps most surprisingly, it almost feels like a brand-new musical. Verbazend, as they say in the Netherlands.