Invisible at the Bush Theatre – review

Nikhil Parmar’s one-man play runs at the west London venue

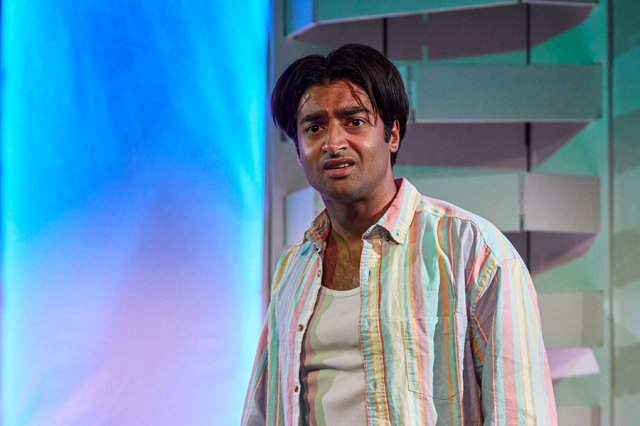

Returning to the Bush prior to a New York run in the Brits Off Broadway season, writer and performer Nikhil Parmar’s one-man play Invisible takes the form of underemployed actor Zayan’s existential crisis that explores the position of brown people in the entertainment industry. Entering the stage to James Bond-esque music, Parmar/Zayan laments that he’s too short and, above all, too brown to play his idol and establishes a contract between performer and audience involving convoluted logic. ‘This isn’t my truth, it’s a truth’, he states. Quite what any of this means is never clear.

The play is set in Britain sometime in the future after peace in the Middle East has been achieved and Islamic fundamentalism has been entirely eradicated and consigned to the past. A “comfortingly racist” newscaster informs us that Chinese extremism is now the problem. For Zayan, this isn’t good news as it means that work playing villains has dried up. An acquaintance’s sitcom Jumping Jihadis has been cancelled as it’s now deemed irrelevant. “At least we existed when we were the bad guys,” he observes ruefully.

Zayan is depicted as a hapless schmuck who breaks the fourth wall with accounts of his sitcom-esque escapades, some of which are quite amusing. His ex-girlfriend Ella, with whom he has an 18-month-old daughter, is now living with Terence (a British Korean actor who’s doing very well out of the trend for Chinese villains), his nemesis from RADA. Aggrieved at being described as “passive”, he flits between working as an incompetent weed dealer for his cousins and preparing for an audition to play an Indian doctor in a period drama starring Hugh Bonneville. He also has unresolved grief regarding the death of his younger sister. These threads quickly get tangled and nothing is followed through in a satisfying manner.

Parmar is a dynamic performer and while Zayan is never endearing (that isn’t the point) he has enough underdog energy for the audience to sympathise with his barely disguised disgust in responses to Terence’s humble bragging. The other characters are distinguished by exaggerated accents: he tells us that accents aren’t his strong point (a cousin who has never left Watford affects an African American accent). Georgia Green’s production, played against Georgia Wilmot’s abstract set, would benefit from a sharper sense of irony as it isn’t always clear what’s supposed to be satire and what is in earnest. The dramatic climax when Zayan leads a race riot in order to be noticed is awkwardly fudged. He steps into the audience for emphasis but it’s uncertain what exactly is supposed to be emphasised.

It would have been more effective to have ended with the feedback from the TV producers as a culmination of the show’s meta dimension rather than a sad but sentimental flashback. The themes are all interesting and important but in its current form, it makes for a chaotic hour.