International artists can be the making of British theatre

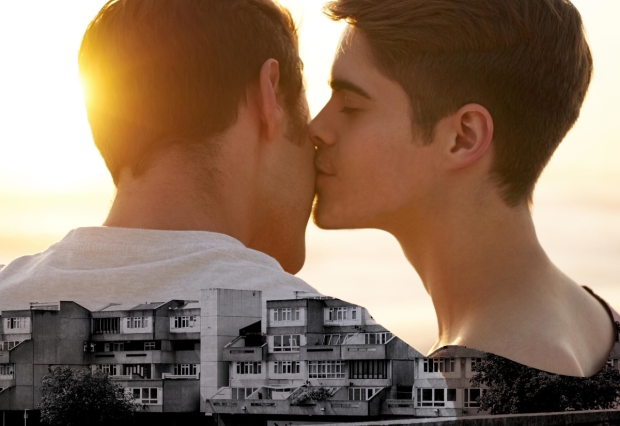

© CAKE Images LLP//National Theatre of Korea

International artists can be the making of British theatre. Paradoxical as that sounds, you only need look at all the stripped-back stagings knocking around to see the influence of Ivo van Hove. A small selection of the Belgian directors shows – none more so than his steely, spartan A View from the Bridge – have shifted the prevailing style of our theatre. Pared back has become par for the course.

That's what makes the London International Festival of Theatre (or just LIFT), which kicked off last weekend, quite such an important occasion for British theatre. A month-long programme of shows and events pulled into the capital from all over the world, it acts as a kind of theatrical intervention. By showing us other ways one might use the stage, other styles and approaches, it sends ripples out through the culture at large.

The LIFT founders initially met with scepticism and suspicion

There are plenty of examples. Elevator Repair Service's eight-hour Gatz might be responsible for a rise in literature staged faithfully, from Simon McBurney's Beware of Pity to National Theatre Wales' ILIAD. Rimini Protokoll and Lola Arias' work with real people – construction workers, children of Chile's revolution and Falklands War vets – preceded those at the Young Vic and elsewhere, while Campo's shows made with children and work with disabled performers by Back to Back and Nalaga'at have also led the way. It runs a long way back too: through De La Guarda's Fuerzabruta and its immersive circus, through Deborah Warner's proto site-specific St Pancras Project, through public spectacles by Urban Sax and Stationhouse Opera.

© Jade Mainade

When Rose Fenton and Lucy Neal launched the festival back in 1981, they initially met with scepticism and suspicion. LIFT was, after all, the first major open invite to international artists since Peter Daubeny's World Theatre seasons wound up in 1973. "People said, 'But why? Isn't British theatre the best in the world?" one remembered in a old Theatre Voice interview. No-one would say that now, even if British theatre is still, broadly speaking, as insular as it ever was.

One producer told me that her company's shows generally skip the UK because the deals out theatres offer just don't stack up

The Barbican's retreated since the days of BITE, the National has only hosted Steppenwolf in 15 years and we can only hope Kwame Kwei-Armah maintains David Lan's internationalism at the Young Vic. Only last week, at a festival in Ruhr, one globe-hopping producer told me that her company's shows generally skip the UK because the deals out theatres offer just don't stack up.

Yet, the value of such visits is undeniable. They shake our sense of the stage up and out of itself, and LIFT's opening shows have show that straight off. You only had to be hit by the wall of wailing song in Ong Keng Sen's operatic Trojan Women – a melding of K-Pop and ancient Korean pansori – to feel that. It turned the human voice into a visceral experience. Gob Squad's Creation (Pictures for Dorian) functions more like a staged essay, mixing participation with personal revelation into a meditation on aging, invisibility and art. It blurs the line, brilliantly, between process and performance.

There's a sense that LIFT has settled into itself of late

In that Theatre Voice interview, Fenton and Neal explain why LIFT runs biennially: "We recognised that a two-year cycle was very healthy, in terms of being able to explore London really widely, but also to be able to reinvent the festival every time." The fallow year allowed them to step back and assess, to see what's missing from British stages and make its programming count. It was, from the off, a targeted intervention.

Artistic director Mark Ball kept that up the decade he was in charge, yet there's a sense that LIFT has settled into itself of late. It's found its footing, and with it, a formula and it's telling that eight of the 12 international artists programmed by this year's guest AD, David Binder, have played LIFT before. Even if that makes this festival seem something of an interim period, ahead of Kris Nelson's takeover in 2020, I'd bet anything that LIFT still leaves a mark.