Allow children to make theatre and who knows what the future might bring

As Coney’s immersive piece, created by kids for adults, runs in London, Matt Trueman looks at what can happen when you let children run riot

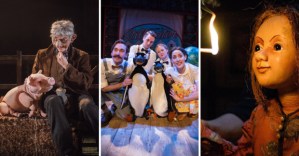

(© Natalie Raaum)

I spent my Sunday night in the dark recesses of children’s minds – which beats Call the Midwife any day. For the last three years, Coney, a company that calls itself an 'agency of play', has been working with children aged between 6 and 11 to create a piece of immersive theatre.

Housed in the basement of a disused carpet factory in the shadow of the Shard, The Droves provides a reminder of just how macabre and surreal young imaginations can be. Far from being fairytale fluff – all princesses and ponies – it inducted its adult audience into a dystopian future in which abandoned sweatshop carpet-making kids had been left to fend for themselves.

When children are allowed to be theatremakers they’re empowered in a totally different way

One flight of stairs down, in a dank, gloomy cellar, we were led through a forest of Christmas trees tangled in thread full, apparently, of "beasties". ("Don’t worry," our intrepid guide told us, "they don’t often eat humans".) Once we had proved ourselves worthy of joining this secret society of left-behinds – a process that involved being barked into revealing our most embarrassing secrets – it was our job to help them create a child. Their previous attempt had gone awry: a carpet-child hybrid sat sadly in one corner, begging to be put out of its misery. All we had to do was get past the guardian gorilla and give them "our bits": fingernails, locks of hair, gobs of spit.

Did it make complete narrative sense? Not exactly, but The Droves was absolutely their show to own. With a guiding hand from director Tom Bowtell, the stuff scratched out of their heads had been shaped into a show – one that had all the hallmarks of children at play: a den made of cardboard, an adult-free zone, the gleefully infantile demanding of "our bits". The honesty of that hands-off approach, allowing children to create largely uncensored, is what gives adult audiences a glimpse into the child brain. Art starts to look like wish fulfilment.

It’s fascinating how often children use the opportunity to confront or affront adult audience

When children are allowed to be theatremakers in this way, not just actors in a school play directed by adults, they’re empowered in a totally different way. They’re given licence to create; a process in which examine themselves and their world and a platform on which to express themselves. It’s fascinating to me how often they use that to either confront or affront adult audiences. The Droves repeatedly put us on the spot, be it in demanding answers of us or setting us riddles. The teenagers that worked with Ontroerend Goed did much the same: challenging us to see the world through their eyes in Once and For All… or, in Teenage Riot, pelting footage of us with tomatoes. The Almeida’s Young Company, comprised of teenagers and young adults, put us through the mangle of a personality test in From the Ground Up, chucking in a fair few curveballs for good measure. Onstage, kids are in control. It’s an upset of the usual order.

That’s why it’s so cheering that companies like Coney or Ontroerend Goed are working with young participants. They offer proof – not to mention first-hand experience – of what theatre can be and do; that it doesn’t simply mean standing centre stage and remembering one’s lines. Rather it is a public platform and so a political one. It activates its actors and enfranchises them.

Time was young theatremakers only discovered this sort of activated practice when they got to university. Before then, you might be exposed to a menu of Brecht, Brook and Berkoff – with a sprinkling of Frantic Assembly on top. Nowadays, it’s far, far more common. Not only are Kneehigh and Punchdrunk on the A-Level syllabus, they’re working, practically, with young participants. The possibilities of that are enormous – and vastly exciting. If today’s six year-olds are making immersive site-specific shows, who knows what they’ll start making in 20 years time?