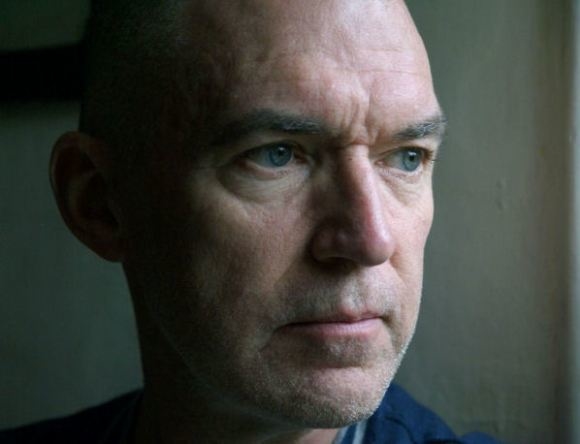

Alan Oke – from Grimes on the Beach to Anna Nicole

The doyen of psychological operatic acting discusses his career as a baritone-turned-tenor

Alan Oke's dressing room at the Royal Opera House is cool and ascetic, not unlike the onstage persona the tenor himself often inhabits. In reality, though, the singer for whom 2013 was an annus mirabilis (it spanned everything from multiple roles in Berg's Lulu for Welsh National Opera to the role of Gandhi in Philip Glass's Satyagraha at ENO) is friendly, modest and a paragon of old-fashioned courtesy.

Your psychological acting is as powerful as your singing, so what does your character in Anna Nicole demand of you? J. Howard Marshall is a bit of a grotesque, after all.

Yes, but even though it's a heightened setting where we turn up the volume and the colour a lot, I think of him as real and I can identify with his situation. The piece is skilfully written by Mark-Anthony Turnage and Richard Jones is such a brilliant director. I’ve worked with Richard so often over the years: he makes things easier for you because he’s done so much work of his own in advance. So I didn't have to scrabble around looking for the guy; it always seemed clear to me what was going on with him.

© Bill Cooper

Any tweaks or changes this time around?

Not particularly, except that I’m nearly four years older so that much closer to the nonegenarian he is! But a revival always feels different. We have a shorter rehearsal process because we’re not starting from scratch on this occasion, so it helps that more or less the same people are doing it as last time.

Last year was a special year for you. How did you cope with it all?

There were a few weeks in October and November when it all got a bit busy. It was fine in the end but I did look askance at my diary in a week when I was doing two Satyagrayas (for ENO), two Death in Venices (for Opera North) and finishing off with a live broadcast of Britten’s Saint Nicolas! It was great fun but I was quite glad when I’d got through it all. I’d originally done the Death in Venice at Aldeburgh, a while ago now, but in the intervening years I’d also taken the production to Toronto, Prague and Lyon, so it never felt like starting all over again. That helped. Aschenbach looks like a mountain to climb when you open the score, because he never stops singing, but once you’re up there doing it it’s not a problem. I am so lucky to have sung that part. It’s a privilege. I think it suited me and I had a good time!

Peter Grimes seems to have been taken over by heavier voices than yours recently, so how did Grimes on the Beach come your way?

It came to me through a side door, you might say. It wasn’t a role that was particularly in my mind, especially as so many Heldentenors sing Grimes nowadays; but Jonathan Reekie, who was in charge at Aldeburgh at the time, came to see me in Toronto when I was doing Death in Venice. We met for a coffee and he put it to me. It took me about three seconds to say yes! Originally he was planning to do it with people following the action as it moved around Aldeburgh itself, but eventually it changed to what we ended up with: a stage on the beach. I had a very exciting time with it. I’d covered the part when I sang Bob Boles at the Royal Opera while Ben Heppner was singing Grimes, so I thought I could probably give it a go.

You were completely believable in the role. Did you study acting at all?

Not as such, no. When I was a student in Glasgow 500 years ago (!) we didn’t have opera schools as such; we were just chucked onstage and sang operas. I learnt some obvious things – ‘don’t use your downstage hand’, that sort of thing – but I think I just took to it. Nowadays singers are really taught stagecraft, quite rightly. We didn’t have anything like that. I don’t walk around in character but I do think now and again of something like ‘how would Peter Grimes get on this bus?’. That’s enough for me.

You continue to mix leading roles with character roles. Is that a conscious choice or do you just go where the work is?

I was around 40 when I changed from baritone to tenor and was probably a bit too late for the big romantic tenor roles, so I moved on to what I do. I’m perfectly happy with that. It has to be done properly, whatever it is. You do it with care and attention and love.

How did the voice change come about?

I already had some tenor top notes, but the passaggio [broadly the point at which the voice makes a transition from the chest to the head register] was the thing that took the longest to sort out. If you're not in form it’s the first thing that can give a tenor problems. But I found that once I'd risen above the passaggio I felt comfortable. A baritone doesn’t have too many problems with it but with a tenor it’s make or break. If it’s not sorted, you’re stuffed. The big challenge in becoming a tenor was being able to sustain a high tessitura, but that has been okay for me. I had become slightly jaded with what I was doing as a baritone so I’ve been very lucky having a second bite of the cherry. It’s been great fun being a tenor.

And along the way you’ve become something of a 20th-century specialist.

Other people have said that to me, and I suppose I have. I think it’s because the things I like to do didn't really exist before the last century. I’ve had such exciting repertoire in the last ten years.

Did the huge success of Grimes on the Beach open any doors for you?

I suppose so, because people now realise I can sing that part. I’ve just done it again recently, in Lyon. The next role on my horizon is Captain Vere in Billy Budd, although I can’t tell you much about that yet. Now that, unlike Grimes, is something I did have in mind to sing one day. I’ve always had it as a project. That opera’s got everything: it’s intimate in scale some of the time, but it’s Grimes-like in others so Vere has got to be strong vocally. It’s a full lyric sing.

I know you can't yet say where you'll be singing that, but is it somewhere I can get to without taking a plane?

Er, no. Maybe a boat ride though…