White Noise at the Bridge Theatre – review

© Johan Persson

The Pulitzer-prize winning playwright Suzan-Lori Parks describes her scalding 2019 play as "ripping the face off of civilisation". It begins in familiar territory, with four friends from college reacting in their separate and various ways when Leo, an insomniac who wanders the streets at night, is assaulted by the police.

Leo is black. His partner Dawn, a liberal lawyer, is white. So is his best friend Ralph, who is rich but disappointed that his attempt to get tenure as a college professor was thwarted when they gave the job "to a second-rate person who is black". His girlfriend, Misha, is a vlogger whose show is called Ask A Black; on it she "dials up the ebonics", performing her blackness so that people "looking for the real deal" will call in.

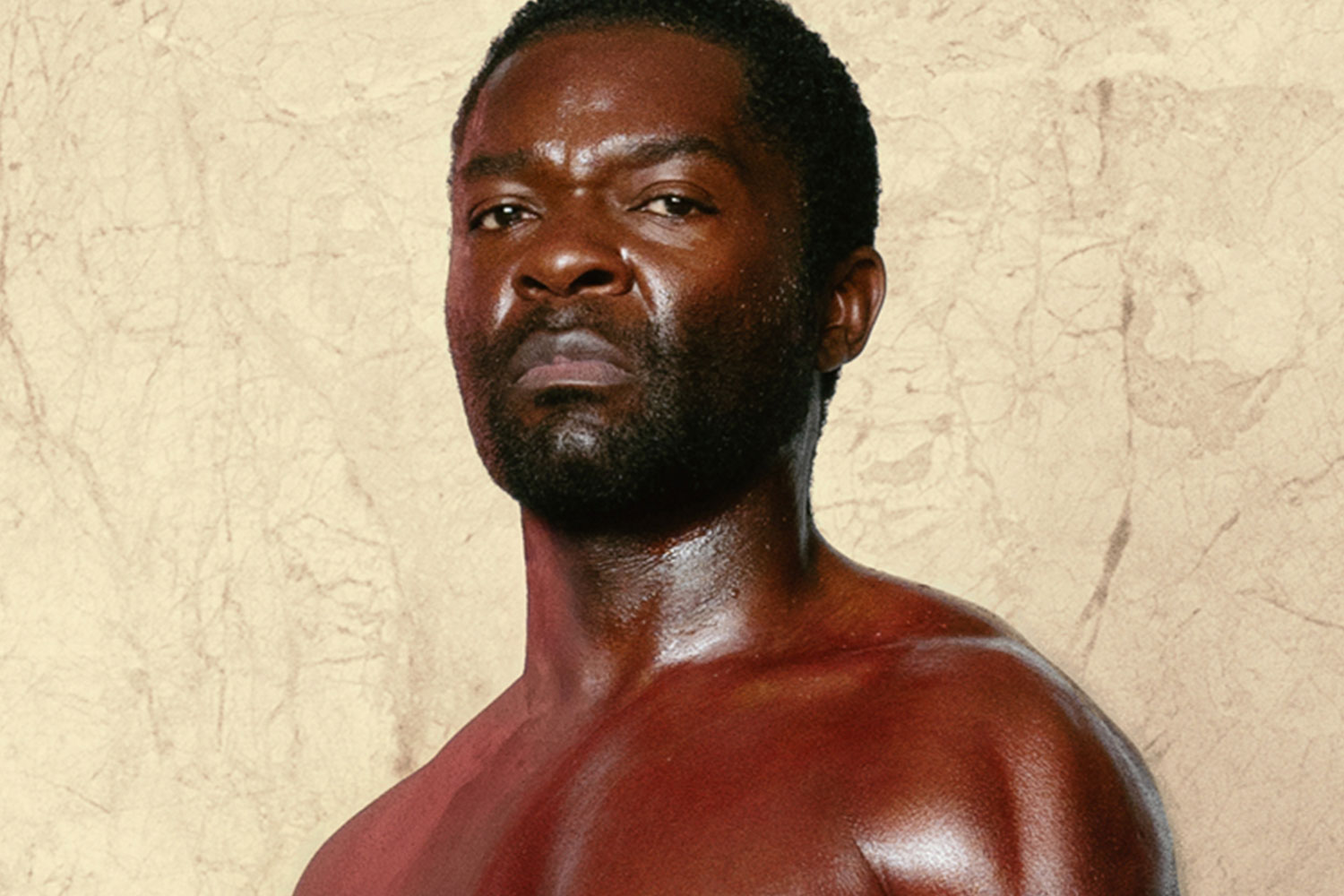

Into this world, performed with the cut and thrust of a clever urban comedy, where a scratch reveals the racial and class tensions just beneath the surface, Leo throws an incendiary bomb. He asks Ralph to buy him, to make him his slave for 40 days. His argument is that because he no longer believes in the system, being owned by a powerful white man will make him feel safe and protected. If freedom is a lie, then enslavement will help him to understand his legacy. "Maybe, just maybe, the chains might contain the seeds of the liberation."

Of course, Ralph reluctantly agrees and from that point onwards the drama grows ever darker as "the Slave quest" infects and exposes the relationships and personalities of four people who thought they were friends – and breaks down all the assumptions of the society in which they live. The magnificence of Parks' writing is that, like all great classical dramatists, you know at some levels what the conclusions will be, yet the tension she builds as she unfolds her arguments has you leaning forward in your seat. She never for a moment lets you rest easy.

Her writing here is less poetic than in other plays such as Father Comes Home from the Wars – which provided the idea for White Noise – but it is nevertheless immense. She holds huge ideas within her naturalistic frame: the themes of what it means to be awake, to be woke, questions about what it is to be righteous and good, wash through the work. There's a bit of Hegel in there, a lot of race theory. But the play never stops working as fierce, gripping drama.

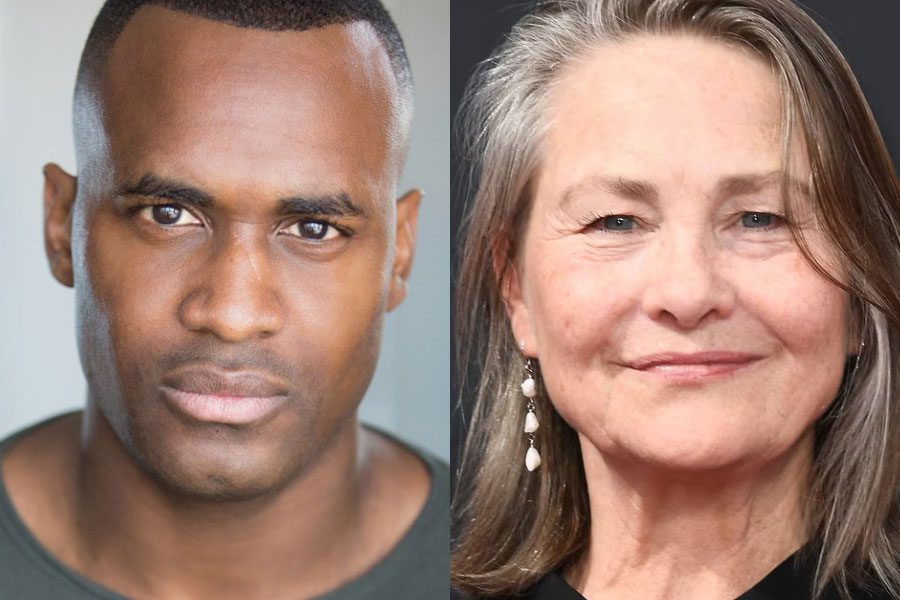

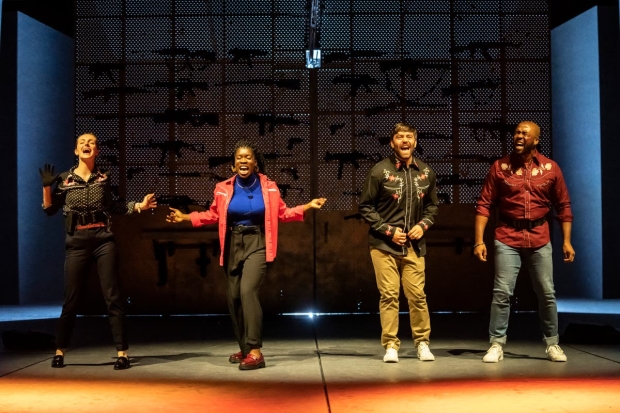

Each character has one moment when they step out of the action to explain themselves. Ken Nwosu's likeable Leo begins the action by folding us into his confidence. From that point Nwosu searingly charts the character's disintegration and despair; the scene where he is shamed by Ralph asking him to wear a slave collar is almost unwatchable. Misha accuses him of "Afro pessimism" but Faith Omole's finely-calibrated performance catches beautifully her own betrayals and delusions, while James Corrigan charts Ralph's rising delight at his assumption of his white privilege with chilling amiability. Dawn, who sees herself as "one of the good guys", and begins to drown her doubts in alcohol, is perhaps the most difficult role but Helena Wilson finds her heart.

Polly Findlay's taut production speeds through its almost three hours with control and concentration. There's an awful lot to pack in and some of the plot developments – the publication of Ralph's short story for example, and the suddenness of the shifts in affection between the women – stretch credulity. But the propulsion of the ideas is strong and devastating.

The move of the action from real to increasingly surreal is matched by the development of Lizzie Clachlan's set, which combines rooms that are subtly marked with distinctions of class and taste, to an almost open arena where a final combat can be enacted. This takes place at the Spot, the shooting range where the quartet bond and bicker: the shooting targets swing through the audience as they fire and check and their scores.

In the original New York production, the Spot was a bowling alley. Its transformation into the setting for America's national pastime perhaps reflects the way that so many of the play's sharpest preoccupations have come into harsher focus since the killing of George Floyd. Certainly that sense of it being absolutely of the moment, makes its coruscating plea for people to find new ways of creating freedom and equality even more necessary.