Review: Love, Love, Love (Lyric Hammersmith Theatre)

© Helen Murray

Mike Bartlett, now of Doctor Foster fame, wrote Love, Love, Love ten years ago. The pertinence of its ferociously sharp, and sometimes simply ferocious observations about the baby boomers and their disaffected Generation X children has not changed in the intervening decade.

This is a savage tragicomedy, both incredibly funny and squirmingly real – and it is clever of the Lyric Hammersmith Theatre's artistic director Rachel O'Riordan to revive it as her second production at her new theatre; its points strike home so strongly that you can hear the audience gasp in recognition and shock.

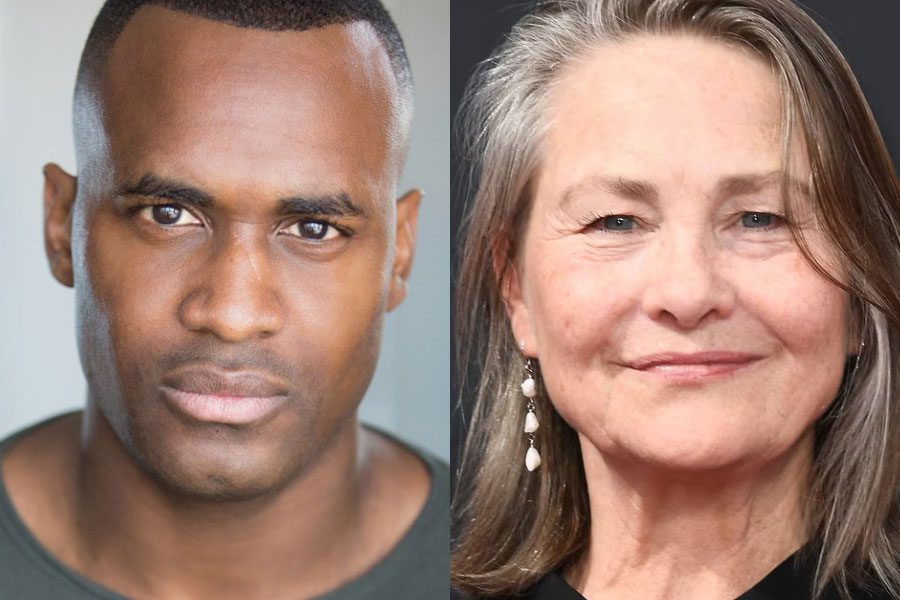

Unusually for a contemporary play, it is shaped in three acts: each covers a particular era in the lives of Sandra (Rachael Stirling) and Kenneth (Nicholas Burns). In the first, set in 1967, on the night of Our World, the first live, international, satellite TV production, the couple meet. She's a liberated vision in purple, he's a louche bloke in a dressing gown; both are at Oxford and their instant attraction freezes out Kenneth's brother Henry, who up until that point thought Sandra was his girlfriend.

We next see them in 1990, on the day of the poll tax riots, when they bicker and drink in front of their alienated teenage children. Finally, we encounter them, post-divorce, on the day of Henry's funeral, when numerous chickens have come home to roost and the consequences of their self-absorbed love of freedom are plain to see. "You didn't change the world, you bought it and then privatised it", says their furious grown-up daughter Rose, pleading for a chance to start her own life.

At each stage, Joanna Scotcher's design charts the taste of the age: horrible green walls, tacky lamps and striped orange and brown sofas for the 1960s; minty green panelling and orange paintwork for the 1990s; cool beiges and greys for 2011. The characters age and change with the help of wigs and clever costuming.

What I like about the play is its razor-like dissection of the way Sandra and Kenneth's belief that the world belongs to them curdles into a selfish pursuit of self-fulfilment that closes out their children and leaves them damaged. What I find harder is its wild switches of tone: it is incredibly funny, but sometimes dangerously close to a cartoon when it depicts the carelessness of their behaviour.

It writes everything large, but O'Riordan's direction is exceptionally well-judged. The scene in the second act – when the mutual cruelty of the parents to each other and to their children is laid bare – is beautifully played, full of silence and incomprehension as well as screaming and unkindness.

Here, as elsewhere, Stirling as Sandra goes over the top. I am not sure women who say things like "I love dancing, it's form and chaos at the same time" ever existed in the 1960s except in the imagination of male playwrights, but perhaps they did; the casual barbarity of her remark to her daughter that "you're pretty when you make the effort" feels much closer to the mark. Stirling amps up all her character's monstrous madness.

In Burns' carefully observed Kenneth she finds an excellent foil; his weakness and apparent affability disguise just as tough a centre. Isabella Laughland and Mike Noble are convincing both as children and as lost adults; she in particular is brilliant at suggesting a yearning for parental approval that never arrives. As Henry, Patrick Knowles is both uptight and wounded. Perhaps Bartlett's sharpest observation is that in 1967, the difference between being 23 and being 19 was so immense that the older brother represented the past, while the younger was the future – a generation gap that has shaped how we live today.