Review: Far Away (Donmar Warehouse)

© Johan Persson

In less than an hour, Caryl Churchill's Far Away conjures a devastatingly bleak dystopia. It begins with a sense of foreboding and ends in total dread. You can't call it enjoyable, but it is impossible to ignore.

It starts when a child called Joan sees something she shouldn't in the garden of the house where she is staying with her aunt Harper. There's her uncle and there are babies and blood. Harper reassures her. When evasions fail, she resorts to comfort, putting a good face on bad things. "You're part of a big movement to make things better. You can be proud of that." In the short scenes that follow, we meet Joan as she performs a task that is the physical equivalent of that evasion of hard, chilling truth about the nature of evil: she makes enormous, fantastical, beautiful hats for beaten prisoners to wear in weekly parades.

By the final scenes we are in a world at total war, the planet is consumed. Every living thing has taken sides. Joan, now married, is somehow on the run. Harper's words have the oddity of fairy tales but the dread madness of truth. The elephants have gone over to the Dutch. Mallards commit rape and are on the side of the elephants and the Koreans. Crocodiles are always in the wrong. Pigs are slaughtered alongside musicians.

Churchill's language has a terrible simplicity and an implacable precision; every word, every half sentence paints a picture that would make you laugh if it didn't want to make you cry. Her point about the human destruction of the order of nature, about what happens when people turn a blind eye to man-made disaster, is so prescient and so far-reaching that Far Away, which premiered in 2000, feels less like a fantasy and more like a warning.

© Johan Persson

It needs direction of scalpel-like clarity and that's what Lyndsey Turner provides. Lizzie Clachan's design of a red felt box allows for swift scene changes and for a shocking staging of the famous parade. There's a tarnished mirror that divides the scenes; Joan peers through it, at the horrors beyond, as if through a glass darkly.

Peter Mumford's lighting and Christopher Schutt's sound both add to the horror, while remaining restrained. It is in its suggestiveness that Far Away is so powerful; it doesn't need to make its effects explicit. As child Joan, Sophia Ally (who will alternate with Abbiegail Mills) catches just the right unease and longing for the disturbing images she has seen to be explained. Turner's attention to detail shows in the way that her feet and legs are dirty, covered in the mud and blood she has trampled through; it's a small thing, but a telling one.

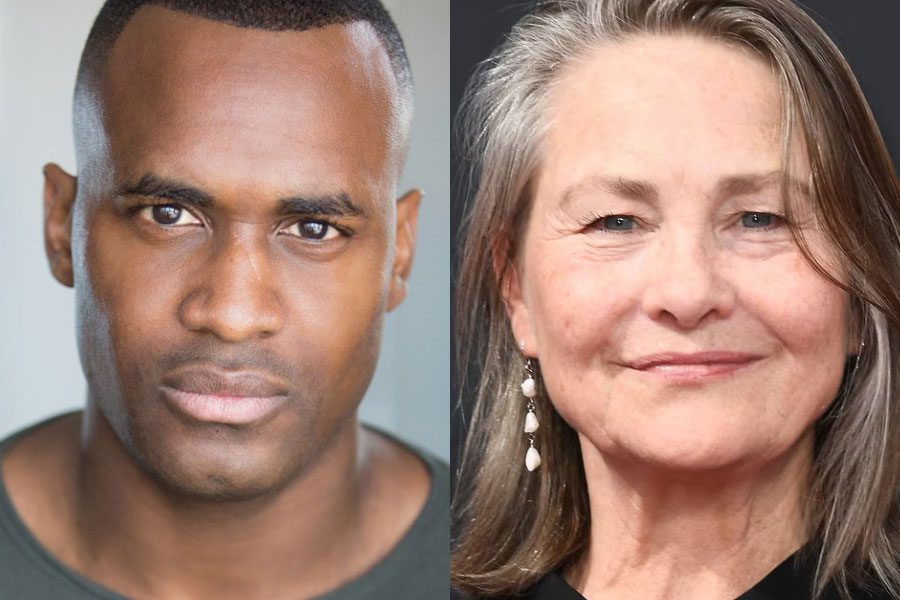

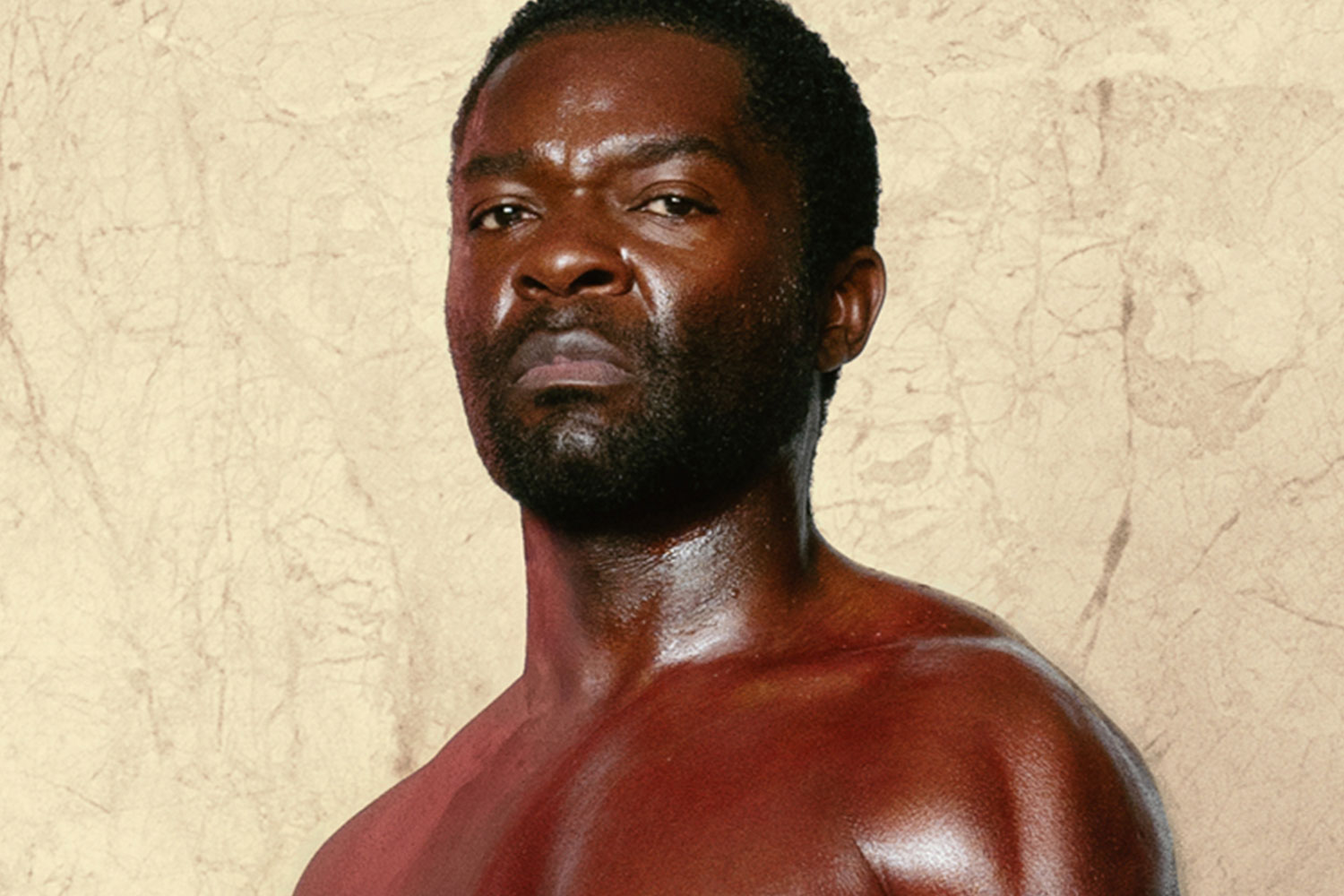

In the same way, Jessica Hynes' harassed, evasive Harper is making a rug that shows a land of beauty and order; like the beautiful feathered and grass hat that grown-up Joan makes, it underlines the way that a longing for order enables people to gloss over darkness, to ignore what they don't want to see. All the cast – which includes Aisling Loftus as adult Joan and Simon Manyonda as Todd, her husband – beautifully capture this moral myopia. Doubt flickers across their faces even as they hope for the best and fail to oppose the wrong.

It's a tiny play, but an immense one. Chilling and thought-provoking. The evening may be short, but you couldn't watch anything else. It's already too much.